Fueled by the FDA’s approval of Wegovy for weight loss in 2021, prescriptions for GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) drugs rose 587% from 2019 to 2024 as usage expanded beyond diabetes management. This explosion in demand led to a shortage in GLP-1 supply, starting with semaglutide, the key ingredient in Wegovy, in March 2022.

During this shortage period, federal law allowed compounding pharmacies to mass-produce copies of GLP-1 drugs to meet demand. Many of these pharmacies partnered with DTC (direct-to-consumer) telehealth companies to distribute compounded medications at prices that were lower than those of branded products.

By October 2024, it was estimated that millions of patients were taking compounded GLP-1 medications. However, when the semaglutide shortage ended in February 2025, some compounders and DTC platforms continued producing compounded GLP-1s, resulting in regulatory scrutiny and legal action from the FDA and semaglutide manufacturer Novo Nordisk.

The significant gap between the demand for GLP-1s and the ability of users to access them through traditional insurer-mediated distribution channels elevated compounding pharmacies and telehealth companies within the US healthcare landscape as alternative pathways to meet GLP-1 demand. As a result, direct-to-patient companies have achieved significant mainstream adoption, although conflicts have arisen with lawmakers and major pharmaceutical companies as a result.

Beyond the immediate controversy, the rise of compounded GLP-1s reveals a structural shift in how healthcare demand is being met in the United States. When manufacturing bottlenecks, high prices, and uneven insurance coverage restrict access through traditional channels, patients increasingly seek alternatives that are faster, cheaper, and more convenient.

Compounding pharmacies and direct-to-consumer telehealth platforms functioned as an informal distribution layer for GLP-1s, demonstrating how quickly parallel care pathways can scale when incentives align. The implications extend well beyond weight-loss drugs: as more high-demand therapies emerge, similar workarounds are likely to appear wherever conventional healthcare systems struggle to keep pace.

GLP-1 Penetration and Demand

The market growth of GLP-1 drugs has been driven by the high prevalence and cost burden of obesity and diabetes in the US. As of August 2023, 40.3% of US adults were classified as obese, and in 2021, about 38.4 million Americans, or 11.6% of the US population, were living with diabetes. The associated expenditures have been substantial: in 2022, the total annual cost of diabetes was $412.9 billion, and obesity-related medical costs in the US were estimated to be nearly $173 billion in 2021.

Following the discovery of semaglutide’s effectiveness in inducing clinically meaningful weight loss, consumer and clinical demand for GLP-1s increased substantially. GLP-1 prescription volume grew from 680K in January 2020 to 4.7 million in May 2025. Over the same period, GLP-1s grew from 18% to 52% of all diabetes prescription volume, indicating a major shift in diabetes treatment patterns.

While GLP-1s had mostly been prescribed for patients with type 2 diabetes as recently as two years ago (as of May 2024), the number of patients without a diabetes diagnosis using GLP-1s for weight loss has risen exponentially — for example, they grew from 21K in 2019 to 174K in 2023, an increase of more than 700%. More recently, a survey conducted in August 2025 found that nearly 12% of Americans had used a GLP-1 drug for weight loss at some point, with GLP-1 sales projected to reach $100 billion by 2030.

Supply and Distribution Constraints

This sudden increased demand for GLP-1s eventually led to supply shortages starting in March 2022, with a key contributing factor being the underlying difficulty of manufacturing peptide-based drugs. GLP-1 production requires the sequential addition of up to 40 amino acids to a peptide chain, a process in which each step can take hours and must be repeated many times. A single batch may require days to synthesize, followed by a lengthy process of downstream purification. These manufacturing characteristics can limit the ability to quickly scale GLP-1 production capacity.

GLP-1 distribution and access were also limited by coverage and pricing dynamics. As of September 2025, GLP-1 drugs were priced at nearly $1K per month, although these costs are expected to fall to as low as $350 or less due to price agreements between GLP-1 companies and the Trump administration. Nevertheless, GLP-1s must be administered indefinitely to maintain weight loss effects, making them a long-term recurring expense for both consumers and insurers.

Struggling to keep up with demand, some payers have responded by eliminating or restricting coverage. As of December 2025, Medicare does not cover GLP-1s for weight loss, and several state Medicaid programs rolled back coverage in 2025. Commercial plans like Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts plan to eliminate coverage of GLP-1s for weight loss in 2026 in response to high drug costs and their effect on insurance premiums. In general, GLP-1 coverage for obesity treatment has been more variable compared to that of diabetes management because obesity has historically not been recognized as a legitimate metabolic disease.

The Rise of GLP-1 Compounding

During drug shortages, the FDA allows an alternative supply pathway known as compounding to fill demand. Traditionally, drug compounding is the practice in which a licensed pharmacist, physician, or outsourcing facility combines drug ingredients to create a customized medicine tailored to an individual patient’s needs.

In the US, compounding occurs under two regulatory categories: 503A compounding pharmacies cover the traditional role of customizing drugs for individual patients, while 503B compounding pharmacies can produce compounded drugs in bulk when certain conditions, such as a shortage, are met. Although 503B facilities are required to comply with current good manufacturing practices, compounded drugs are not approved or reviewed by the FDA, meaning that the agency does not assess their safety, efficacy, or quality.

Beginning in 2022, compounding pharmacies increasingly produced compounded versions of GLP-1 medications, expanding supply during the shortage period, while also appealing to patients due to their affordability and ease of access. Distribution frequently occurred through DTC telehealth platforms, which lowered logistical barriers to obtaining prescriptions and reduced the need for in-person visits. This model was particularly helpful for rural patients with limited local provider access.

As of 2025, compounded GLP-1 drugs were priced at $250-$400 per month, which was significantly lower than the $1K per month price tag for branded products. These lower drug costs greatly expanded GLP-1 access for the uninsured, underinsured, and those denied drug coverage.

The temporary allowance for compounded GLP-1 drugs enabled compounding pharmacies to respond to elevated demand and supported the rapid expansion of a new market segment. By 2024, the market for compounded GLP-1s was estimated to have reached $1 billion. In 2025, 24.3% of Americans who had ever taken a GLP-1 reported using a compounded version, and 11% of consumers obtained their GLP-1 medications through online platforms.

A key player in the compounding space has been Hims, a telehealth platform that distributes compounded medications and personalized treatments. Originally focused on products like generic Viagra and Rogaine, Hims began selling a compounded version of Wegovy in May 2024 for $199 per month, causing its share price to grow by nearly 40%. In the fourth quarter of 2024, GLP-1 sales accounted for 30% of Hims’s $481 million in total revenue, and it was estimated that Hims was responsible for 20% of all compounded GLP-1 prescriptions in the US during that period.

Safety Concerns

The proliferation of compounded GLP-1s was accompanied by safety concerns, largely because compounded drugs were not reviewed by the FDA prior to distribution. One major area of concern was dosing and formulation variability. Compounding pharmacies sometimes produced GLP-1 drugs in varying concentrations and packaging, which could confuse patients. In July 2024, the FDA issued an alert that warned of the risks of dosing errors in compounded semaglutide products after receiving reports of patients self-administering GLP-1s at dosages five to 20 times higher than prescribed.

Other safety concerns emerged around the product quality and ingredient authenticity of compounded GLP-1s. In September 2025, the FDA reported instances of compounded GLP-1 products containing unapproved foreign substances and companies selling drugs to consumers that were falsely labeled “for research purposes.” A 2024 report also found that many active pharmaceutical ingredients for compounded GLP-1s were imported from unregistered foreign suppliers, raising questions about supply chain oversight.

Regulatory and Legal Response

In February 2025, the FDA declared that the shortage of semaglutide had been resolved, marking the end of the GLP-1 drug shortage. Compounding facilities were given until May 2025 to cease manufacturing copies of patent-protected GLP-1 drugs.

However, not all companies ceased production. In April 2025, Hims and Novo Nordisk entered into an agreement that allowed Wegovy to be sold on the Hims platform at a discount. Two months later, Novo Nordisk terminated the partnership because Hims continued to sell its own compounded GLP-1 drugs alongside Wegovy. Novo Nordisk accused Hims of “[failing] to adhere to the law which prohibits mass sales of compounded drugs under the false guise of ‘personalization’ and […] disseminating deceptive marketing that put patient safety at risk.”

In August 2025, Novo Nordisk lowered guidance during its earnings report and partly blamed the production of compounded semaglutide for the reduction. As of September 2025, Novo Nordisk has filed 140 lawsuits and issued 1K cease-and-desist letters against GLP-1 compounders.

The FDA subsequently began cracking down on compounders. In September 2025, the FDA sent thousands of warning letters and issued approximately 100 cease-and-desist letters to companies regarding their use of “misleading direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertisements.” The agency also published a “green list” of acceptable GLP-1 compounding ingredients intended to regulate ingredient sourcing and reduce the risk of unsafe compounded products.

The Future of Compounding

Although large-scale compounding of GLP-1 drugs is no longer permitted, several factors suggest that GLP-1 compounding is unlikely to disappear entirely:

Continued demand for quick and easy access to drugs: The DTC telehealth model remains popular for obtaining personalized medicine outside of traditional clinical settings. Pharmaceutical companies are also trying to capitalize on the success of this model by rolling out their own platforms: Pfizer rolled out its DTC platform, PfizerForAll, in 2024, and Novo Nordisk launched its direct-to-patient program, NovoCare Pharmacy, in 2025.

The establishment of workarounds: Even after the shortage ended, compounders were still allowed to customize GLP-1 products for specific patient needs, allowing companies to create slightly altered versions of GLP-1 formulations to prescribe to large numbers of patients. Two common workarounds have been the use of additives and the adjustment of dosage amounts. As of October 2025, over 80% of compounded semaglutide and tirzepatide prescriptions included supplemental ingredients such as B vitamins (B6, B12, B3) or levocarnitine, which have been presented as providing weight loss support or energy enhancement. Companies like Noom and Hims have also launched programs to prescribe microdosed GLP-1s, claiming that these smaller doses can “reduce metabolic risk, lower inflammatory markers, and even lower the risk of cognitive decline.”

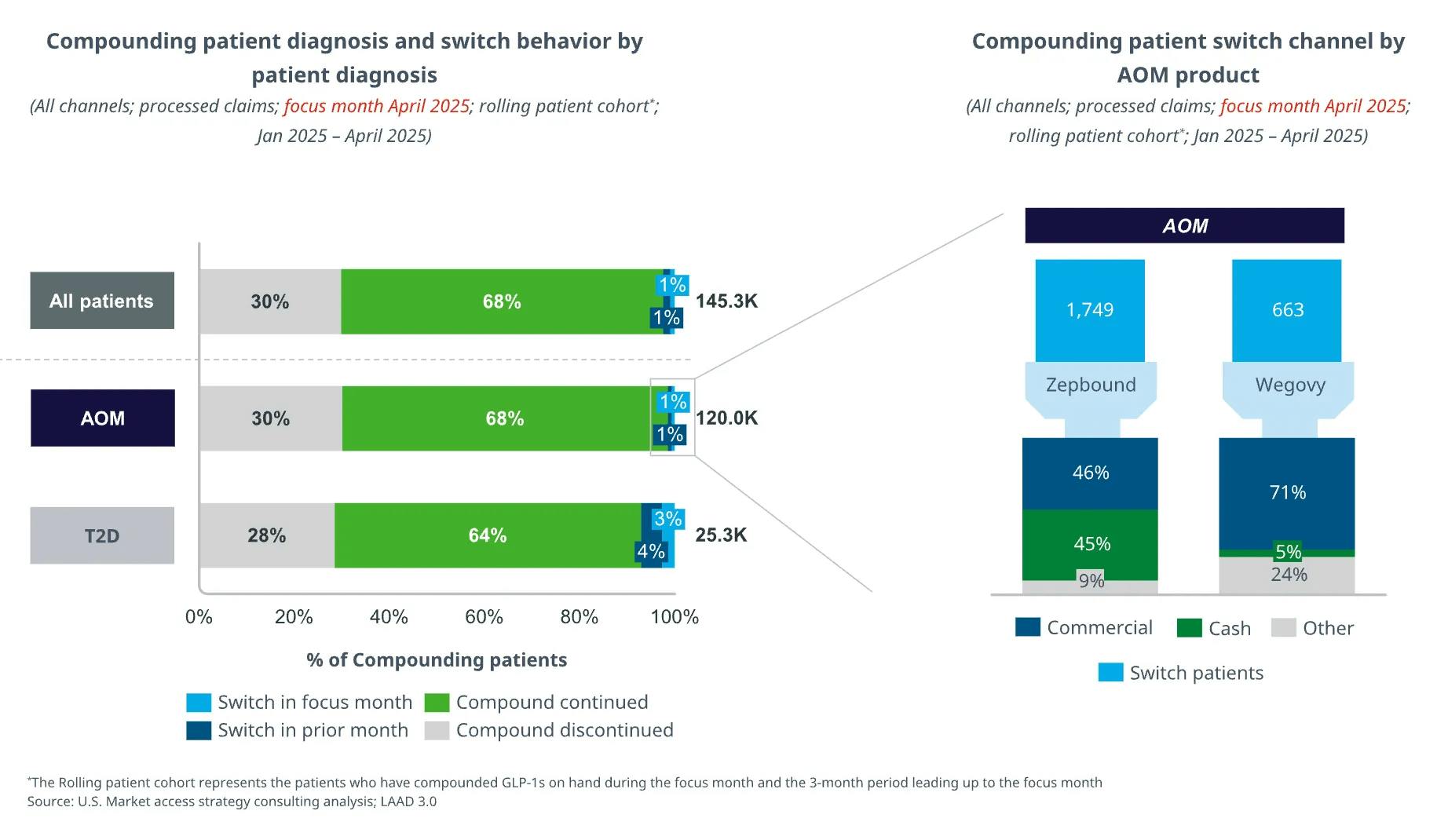

Evidence of sustained patient use post-shortage: Prescription volume and utilization of compounded semaglutide and tirzepatide have continued to grow despite the end of medication shortages, suggesting that compounders may be leveraging additives or dosage adjustments to justify production. Switching from compounded to branded GLP-1 products remains uncommon, with only 2% of patients moving from compounded to branded GLP-1s. Of the patients that switched, nearly half of them paid out of pocket for branded GLP-1 drugs, while the rest relied on commercial insurance to pay for branded drugs, revealing a significant cost barrier to switching.

Source: IQVIA

Pharmaceutical Innovation vs. Access

Debates over compounded GLP-1s reflect a broader tension between incentives for drug innovation and questions of patient access. The traditional pharmaceutical R&D model grants periods of market exclusivity to incentivize investment in new therapies, but high drug prices can limit affordability and patient access. As of 2024, list prices for GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic approached $1K per month despite the drug’s manufacturing cost of less than $5 a month, contributing to ongoing scrutiny of drug pricing practices.

These high prices also affected insurance coverage. As payers roll back coverage of GLP-1s for weight loss to control cost growth, policymakers have explored ways to expand access through public programs. In November 2025, President Trump negotiated a deal with Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk to reduce the price of GLP-1 drugs, resulting in a new voluntary program that allows Medicare beneficiaries to pay $50 for a month’s supply of GLP-1 drugs.

Intellectual property disputes have also unfolded alongside these policy developments. In April 2025, Empower Pharmacy, a large 503B compounding pharmacy in the US, challenged Eli Lilly’s pharmaceutical exclusivity by filing a petition to invalidate Eli Lilly’s tirzepatide patent, arguing that the drug is unpatentable due to prior art.

Meanwhile, manufacturers continued to compete through product development. In December 2025, Novo Nordisk received FDA approval for an oral formulation of Wegovy that demonstrated weight loss effects similar to those of the Wegovy injection. This approval of the first oral GLP-1 drug strengthened Novo Nordisk’s intellectual property moat and its lead in the GLP-1 market amid fierce competition from Eli Lilly and compounding pharmacies.

A New Era of Healthcare Distribution

The GLP-1 compounding boom demonstrated that patients are increasingly use alternative, consumerized care pathways when conventional channels are slow or expensive. Telehealth, cash pay, and compounding pharmacies functioned as a scalable distribution system for GLP-1s, filling a supply and access gap for a blockbuster therapy. These channels did more than fill a temporary gap: they demonstrated that patients will route around insurer-mediated pathways when access is slow, coverage is uncertain, or prices are high. In doing so, these pathways expanded drug access and customization, but often with less oversight and frequent conflicts with patent protections.

The growth of compounding also highlighted a longstanding tension in biopharma: patent exclusivity is designed to reward costly R&D, yet high prices and uneven coverage can create strong pressure for workarounds. Compounded GLP-1s exposed how quickly those workarounds can now scale. This pattern will likely be reproduced with future high-demand therapies, forcing regulators, manufacturers, and clinicians to balance access, safety, and incentives for innovation as more care moves outside traditional clinical settings and insurer-mediated systems.