Decline in U.S. Shipbuilding Readiness

Throughout history, naval power has consistently served as the bedrock of national strength. A robust navy does more than secure coastlines; it projects influence onto distant shores, safeguards the flow of essential goods, and deters aggression. Over the last two centuries, British and American experiences have demonstrated that whoever holds the reins of naval superiority can dictate trading conditions, broker alliances on favorable terms, and sway the outcome of conflicts across the globe.

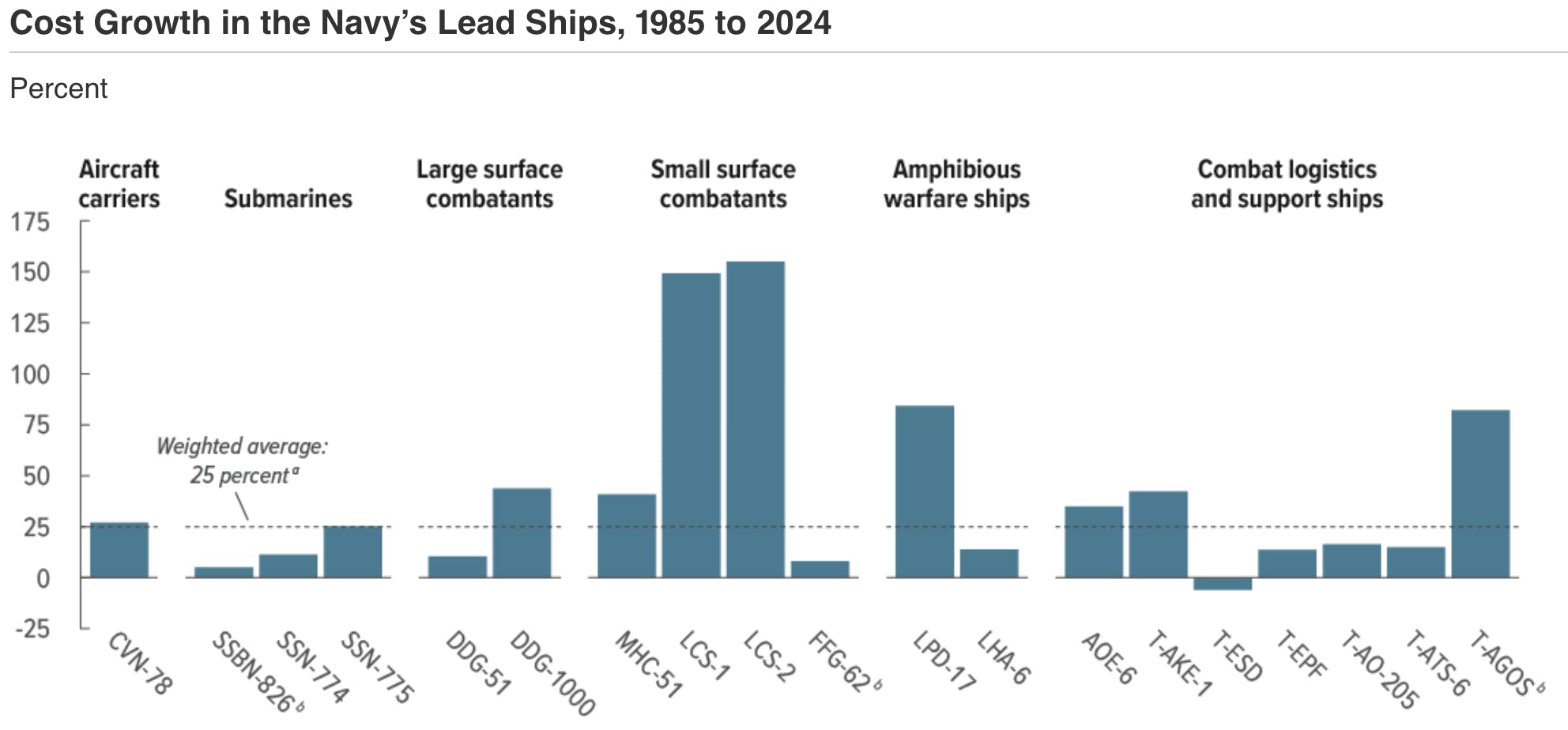

In recent decades, America’s ability to build and sustain a large navy has eroded significantly, with troubling consequences for military readiness. Over the past 20 years, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) has issued roughly 40 reports flagging problems in Navy ship programs. Taken together, these failures have been described as a “lost generation of shipbuilding,” leaving the Navy less prepared just as new threats emerge.

The list of setbacks is long and costly. The Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) program, intended to produce dozens of agile coastal warships, saw its costs double during construction; the Navy cut the original buy from 52 ships down to 35, and is now retiring some of those vessels after barely a decade of service. The futuristic Zumwalt-class stealth destroyer was slashed from 32 planned ships to only three as expenses skyrocketed – at an estimated $7 billion per ship, each ended up even costlier than a Nimitz-class aircraft carrier. Even the Navy’s newest supercarrier, USS Gerald R. Ford, was delayed by unproven technology. Its magnetic catapult, advanced radar, and other advanced features have been marred by cost overruns and reliability problems, to the point that the carrier took years longer than expected to become operational.

Source: Congressional Budget Office

These missteps have real consequences - ship classes have been curtailed or retired early, as evidenced by the aforementioned LCS program. U.S. shipyards today struggle not only to build new warships on schedule, but even to keep up with repairs on the existing fleet. By one Navy estimate, the United States is 20 years behind in maintenance work, with some ships being decommissioned simply because shipyards lack the capacity to overhaul them. All of this means fewer deployable ships at any given time – a direct hit to readiness. Long gone are calls for 600-ship fleets — today's Navy aims for a fleet of 381 manned ships and 134 unmanned vehicles, including 78 unmanned surface vessels (USVs), as outlined in its Fiscal Year 2024 30-year shipbuilding plan. However, even this target is considered ambitious.

The decline of American shipbuilding isn’t a sudden development, but rather the cumulative result of post-Cold War downsizing and industrial atrophy. The U.S. once viewed its shipyards and merchant fleet as strategic assets (and subsidized them accordingly), but those supports were removed in the 1980s, and the industry withered. By 2016, the number of shipyards capable of building large vessels had declined by 80%, and annual output had declined by nearly 90% relative to 1953 levels. As of 2023, the US accounted for only 0.10% of global commercial shipbuilding.

With naval ship construction now concentrated in only a handful of specialized U.S. yards and a lack of skilled workers or equipment on standby, there is little surge capacity. If a shipbuilding program falters, there are few alternatives to pick up the slack since most U.S. naval warships only have one specialized builder. In short, America’s naval industrial base has become lean to the point of being brittle, undermining the nation’s ability to field enough ships quickly in a crisis. This predicament would be alarming under any circumstances, but it is especially so given the rapid naval buildup of a rising competitor.

China’s Rapid Naval Expansion and Strategic Challenge

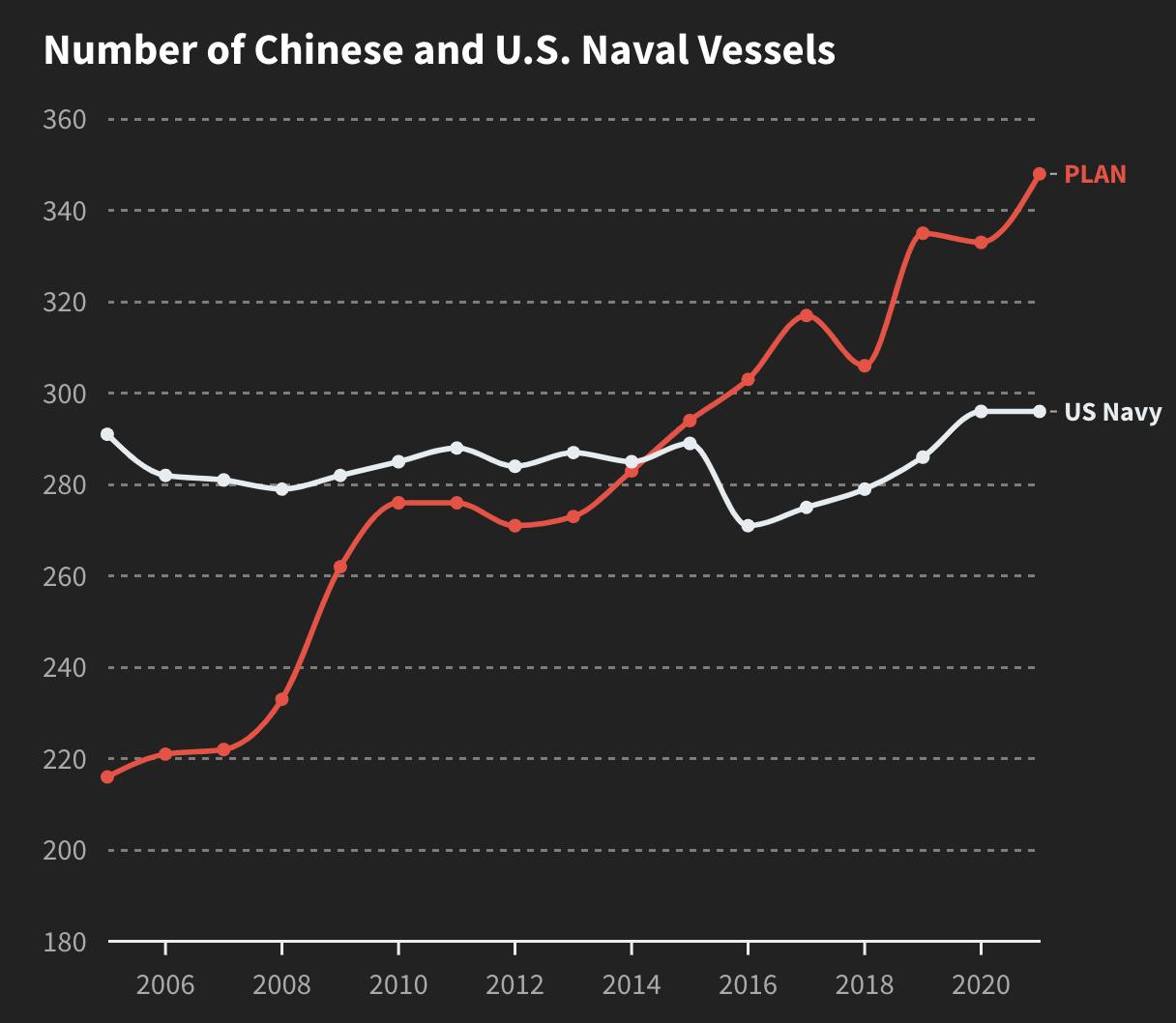

While U.S. shipbuilding has sputtered, China has been racing in the opposite direction – expanding and modernizing its navy at an unprecedented pace. In the span of about 25 years, China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has transformed from a coastal defense force into a blue-water fleet operating across the Indo-Pacific and beyond.

According to the U.S. Department of Defense, China now fields the largest navy in the world, with roughly 355 battle-force ships (not counting dozens of smaller missile-armed patrol craft) and is on track to grow to 420 ships by 2025 and about 460 by 2030. By comparison, the U.S. Navy today has under 300 deployable ships, a figure essentially flat or even declining – the Navy projects around 290 ships by 2030, a decline from 2024 levels. In other words, barring a dramatic change, the U.S. fleet will remain far smaller than China’s in sheer numbers.

Source: CSIS

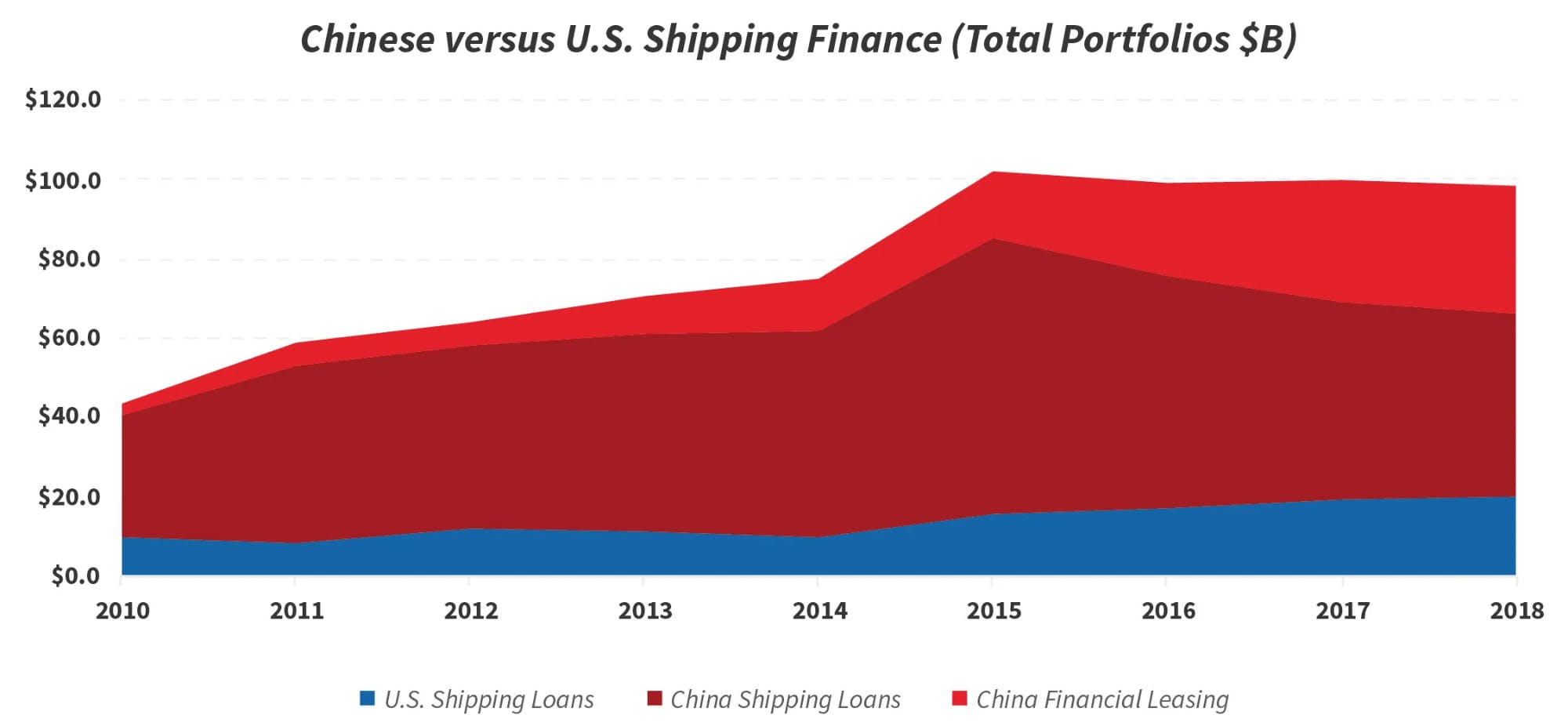

China’s naval growth is not just about quantity – it’s also about capability and strategic ambition. Beijing has invested in advanced destroyers, stealthy submarines, large amphibious assault ships, and even aircraft carriers. Just as important, it has built a vast shipbuilding infrastructure to support this expansion. China’s government heavily subsidizes its shipyards, with CSIS estimating $127 billion in state support between 2010 and 2018 — a figure that has likely increased since.

Source: CSIS

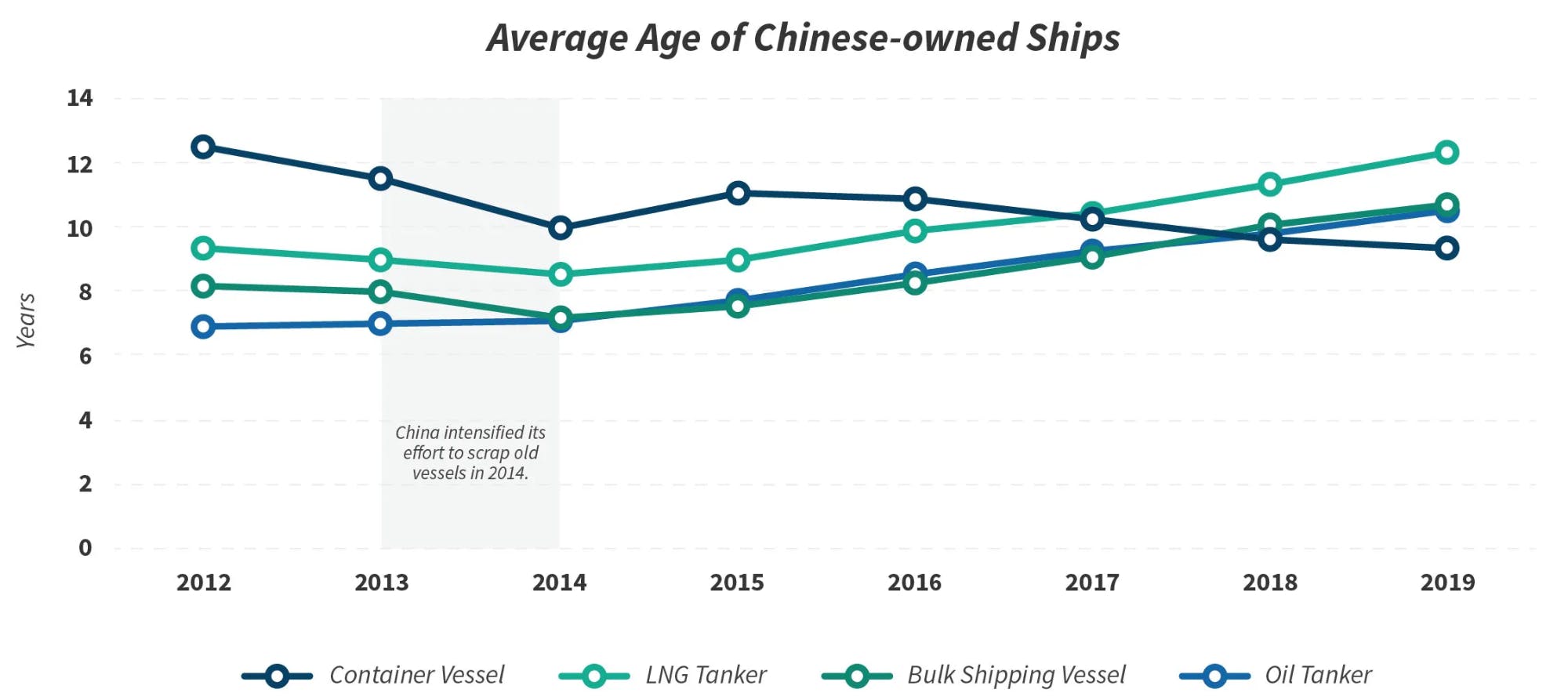

In an effort to boost demand, China also introduced a 'scrap and build' subsidy program in 2010, allowing Chinese shipping companies to upgrade their fleets at substantially reduced costs. Initially, companies were required to destroy older vessels before receiving the full subsidy. However, beginning in 2014, firms became eligible to receive subsidies even before initiating the construction of replacement vessels. This adjustment increased their incentive to retire older ships, as companies could now access subsidy funds upfront.

Source: CSIS

Moreover, the sheer size of China’s shipbuilding capacity is staggering, with over 20 major facilities (building both warships and commercial vessels) and over 140 dry docks for ship construction and repair. This industrial capacity translates into astonishing output: a leaked U.S. naval intelligence briefing noted that Chinese shipyards have a manufacturing capacity of roughly 23 million tons of shipping per year, compared to under 100K tons in the U.S. – a more than 200-to-1 advantage. In practical terms, China can launch new ships much faster and in greater volume than the United States can. The PLAN’s expansion has already given China a powerful presence in its regional waters, and it’s increasingly operating in the Indian Ocean, Mediterranean, and other far-flung areas.

The Shift Toward Autonomous and Attritable Systems

Confronted with these challenges, American defense planners are increasingly looking to new technologies and operational concepts to level the playing field. One of the most promising avenues is the development of autonomous and attritable systems for naval warfare, which can be made relatively cheap and in bulk. The importance of these systems is already evident in real-world conflicts and simulations. A 2020 RAND study of U.S.-China conflict scenarios found that having an advantage in interconnected and attritable unmanned vehicles could give U.S. forces a major edge, potentially tipping the balance in a clash with China.

Nowhere has the importance of these systems been more evident than in Ukraine, where the use of USVs in the Black Sea has imposed severe operational and economic costs on Russia. Beyond economic warfare, USVs have directly shaped battlefield dynamics by neutralizing high-value Russian assets at minimal cost. The use of relatively inexpensive USVs to deploy FPV drones, which successfully destroyed Russia’s costly Pantsir-S1 air defense system (valued at $15–20 million), highlights the asymmetric return on investment. Large-scale strikes, such as the August 2023 Kerch Bridge attack, forced Russia to deploy S-400 air defense batteries away from frontline operations, reducing their overall effectiveness.

The U.S. Department of Defense has taken notice. In 2023, Pentagon leaders announced a new initiative called “Replicator” aimed explicitly at fielding swarms of autonomous weapons on a fast timeline to counter China. Deputy Defense Secretary Kathleen Hicks described it as a plan to deploy “thousands” of small drones across multiple domains (air, land, and sea) within 18–24 months. The first phase, backed by roughly $1 billion in funding, focuses on massed lethal autonomous surface drones and loitering munitions to help blunt a potential Chinese invasion of Taiwan. This marked a shift in Pentagon priorities toward agile, attritable systems that can be produced and deployed rapidly, rather than exquisite but slow-to-field programs.

Moving Beyond Big Warships: A New Paradigm

The embrace of autonomy also reflects a growing realization: the U.S. cannot rely on a few giant warships to guarantee control of the seas in the modern threat environment. Large vessels like aircraft carriers, cruisers, and big-deck amphibious ships pack tremendous firepower, but they also concentrate huge value in single targets. In an age of precision-guided missiles, that makes them potentially vulnerable “eggs in one basket.” For instance, China has developed long-range anti-ship ballistic missiles (notably the DF-21D, dubbed the “carrier killer”) specifically to target U.S. carriers from afar.

Some analysts have warned that, without new defensive measures, a multi-billion-dollar U.S. supercarrier could be turned into a “sitting duck” by a much cheaper missile salvo. The traditional answer to these threats was to add more armor, more point-defense weapons, or more electronic countermeasures to each ship, while also layering on more and more functionality in the hope of creating an all-encompassing platform. But this approach backfired: costs ballooned, ships became overengineered and brittle, and maintenance burdens soared. All of this exacerbated the cycle of bigger, pricier hulls that could only be built in limited numbers. Today’s reality calls for a different approach: distributing combat power across many more platforms, some of them unmanned and relatively inexpensive. By shifting toward fleets of smaller, autonomous vessels, the Navy can make its force more flexible, resilient, and sustainable.

Small, robotic craft have several advantages that complement (and in some roles, could replace) their larger counterparts. First is sheer manufacturability. A 10-foot or 20-foot unmanned boat can be built in days or weeks on an assembly line, not years in a specialized shipyard. They require far fewer unique components – no onboard crew facilities, for example – and can potentially be produced by commercial boatbuilders or even adapted from civilian designs. This means that in a crisis, production of such vessels could be ramped up quickly, tapping into the broader manufacturing base.

Second, a swarm of small vessels is inherently harder to defeat than a single large one. Ten autonomous boats carrying surveillance gear or weapons can disperse over a wide area, making it difficult for an adversary to track and destroy them all. This resilience by numbers is a key reason the Navy is experimenting with concepts like “distributed maritime operations,” which aim to network many smaller nodes together rather than depending on a handful of high-value units. Smaller unmanned systems are not only cheaper to acquire but also far less costly to lose. For the price of one guided-missile frigate, the Navy could deploy dozens of armed USVs, each replaceable far faster than a crewed ship and without risking sailors’ lives, dramatically complicating an enemy’s calculations.

None of this is to suggest the U.S. Navy will (or should) scrap its carriers and destroyers overnight. Capital ships still have roles including power projection, air defense, and as floating airfields and sea bases that unmanned craft cannot yet perform at scale. But the Navy’s own leadership acknowledges the need for a more balanced and distributed fleet. The latest Navy force structure assessments and strategy documents signal a shift toward a “more distributed fleet architecture” with a much greater use of unmanned vessels alongside traditional ships. For example, instead of sending one or two warships to patrol a chokepoint or shadow a potential adversary, the Navy could deploy a dozen mini-drones and a couple of larger unmanned vessels, covering more area and presenting more dilemmas to any opponent. This concept has already been demonstrated in exercises: the Navy’s Unmanned Integrated Battle Problem exercises in 2021 tested teams of unmanned surface and air vehicles working together with manned ships, showing promising results in extending sensor range and targeting abilities.

Taken together, the historical dominance of sea power, the decline of U.S. shipbuilding, the rapid rise of China’s navy, and the emergence of autonomous warfare point to a clear conclusion: the United States must adapt quickly to maintain its maritime superiority. By prioritizing smaller, software-driven vessels, it can secure its naval dominance for decades to come.