Electric Vehicle Dominance

In March 2025, Chinese electric car company BYD, which stands for “Build Your Dreams”, overtook Tesla as the world’s largest seller of electric vehicles. In 2024, BYD sold about 4.3 million vehicles globally, while Tesla only sold about 1.8 million worldwide. This data point is only the latest in a chain of supply and manufacturing shifts that have led China to dominate the global EV market in 2025, forcing American automakers to reconsider their operations.

As of December 2025, executives of major American automakers like Ford regularly visit China to test drive vehicles, and have even flown units back to Detroit for closer study. Ford’s CEO Jim Farley said that Chinese electric vehicles and quality were “the most humbling thing I’ve ever seen.” Despite his doubts about BYD’s potential a decade earlier, Elon Musk reversed course in a 2024 interview, saying Chinese EV makers such as BYD will “pretty much demolish” most competitors without trade barriers.

BYD is not the only automaker posing competition for Tesla and American car makers. In 2025, six of the world’s top 10 EV manufacturers are Chinese companies, and China produces more than 60% of all electric vehicles globally. In cities like Shenzhen and Shanghai, buses are electrified, and almost half of China’s car sales in 2024 were electric (two-thirds of electric cars sold globally in 2024 were sold in China, up from half of all electric cars in 2021). On a monthly basis, electric car sales have surpassed conventional car sales since July 2024, and are only growing in popularity.

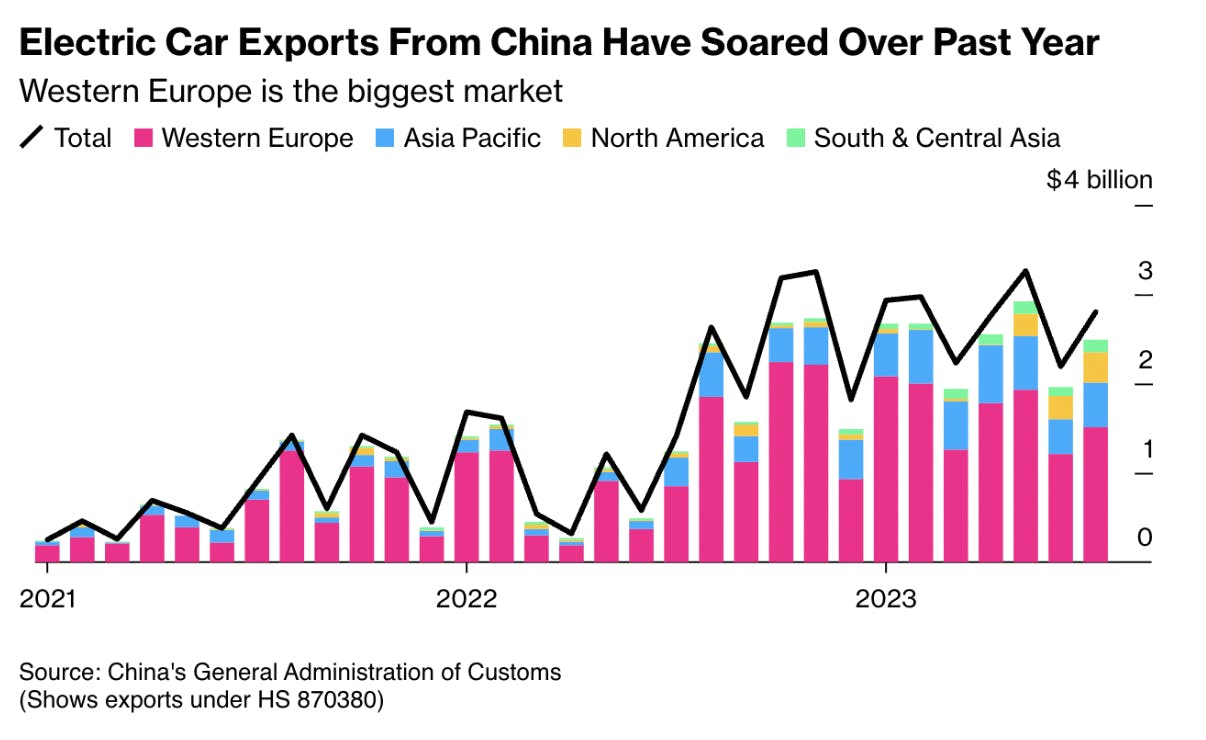

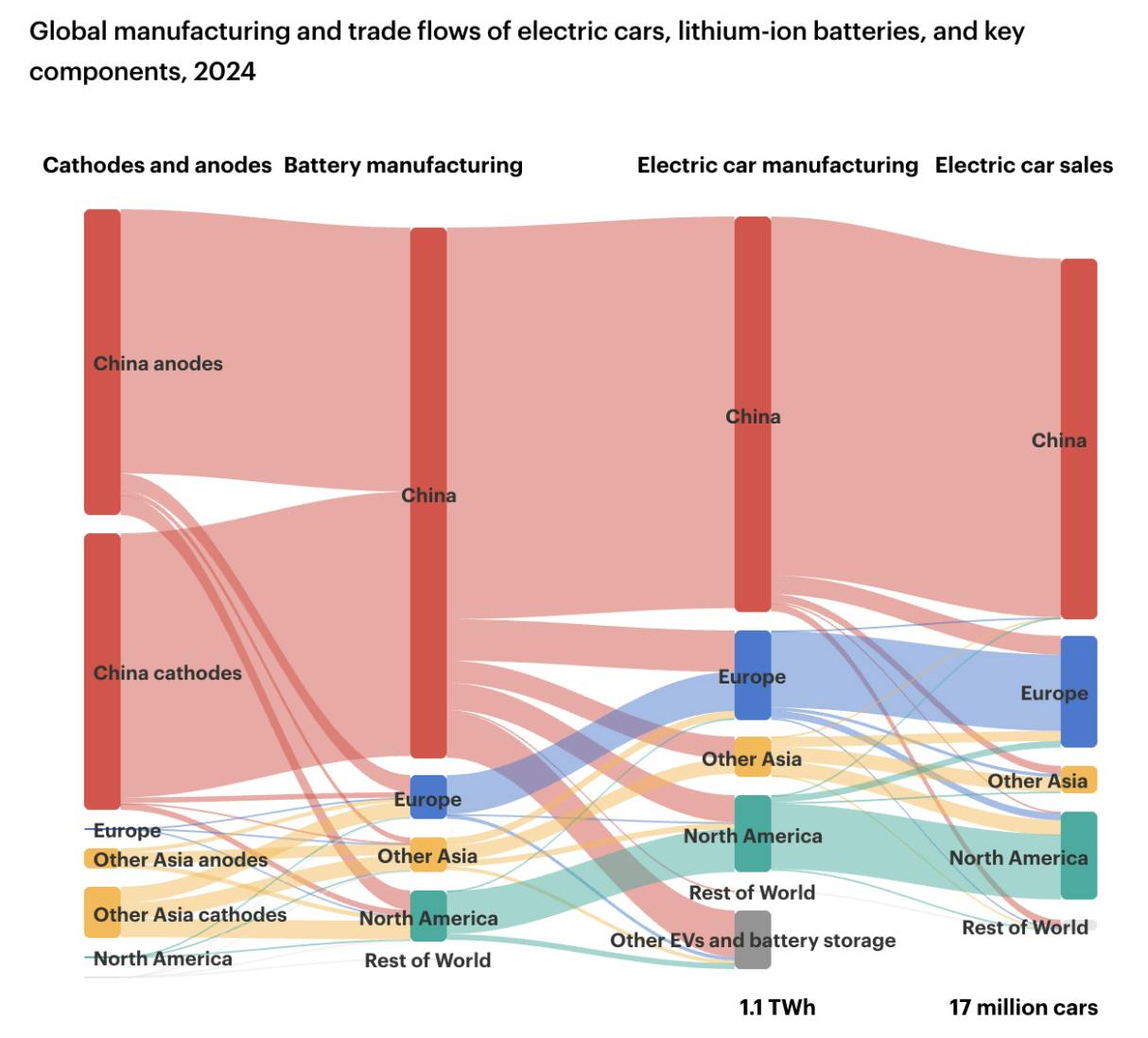

Beyond domestic popularity, China also manufactures the majority of the electric cars and batteries sold globally. China accounted for more than 70% of global EV and EV battery production in 2024, and 40% of global exports. Despite tariffs as high as 35% for certain companies as of December 2025, Chinese EV brands doubled their share in the European car market between April 2024 and April 2025.

This begs the question: how did we get here? How did China, a country that used to copy the designs of Ford, General Motors, and Tesla, come to dominate electric-vehicle production and manufacturing, and how can America respond? The answer lies in the supply chain of electric vehicles, which favors China’s geological and manufacturing resources, and in the innovations Chinese EV-makers are bringing to vehicles.

Source: International Energy Agency

Making Batteries: The Powerhouse of the EV

The fundamental difference between electric and traditional gas-powered vehicles is the power source. While traditional vehicles rely on spark-ignition gasoline engines, EV motors are powered by electricity stored in rechargeable batteries. As of December 2025, EVs rely primarily on lithium-ion batteries, which are favored on the basis of their light weight relative to overall energy storage capacity and longer lifetimes compared to comparable batteries. China controls significant components of the EV battery supply chain, including extraction, refining, and manufacturing of key minerals.

Extracting Minerals

Lithium-ion batteries require multiple minerals, including lithium, graphite, nickel, cobalt, and manganese. Electric cars use six times more rare earth minerals than conventional cars, primarily due to battery requirements.

Source: Let’s Talk Science

As of December 2025, China controls the vast majority of mineral production and extraction worldwide, accounting for 69% of global mining and 92% of the processing capacity for rare earth metals. Through investments in mines around the world, Chinese companies largely dictate overseas mining and refining volumes, as well as sale prices, for rare earth minerals and some traditional metals.

China owns mining projects and investments around the world. Specifically, China controls 41% of the world’s cobalt (through investments in Congo cobalt mines), 78% of graphite (largely mined in China), 28% of lithium, 6% of global nickel (with plans to become the largest controller of nickel by 2027 through investments in Indonesia), and 5% of manganese. Chinese companies have stakes in mining companies on five continents. American companies have even sold mines to their Chinese counterparts in the past.

Source: S&P Global

Refining Minerals

After raw mineral ores are mined and extracted, processing facilities refine concentrated minerals for industrial consumption. The raw ore is pulverized and treated with heat and chemicals in an energy and water-intensive process. Lithium, for example, is refined through a system of steps in which it is crushed, concentrated, and roasted at high temperatures with acid to leach out pure lithium, which is then precipitated to lithium carbonate.

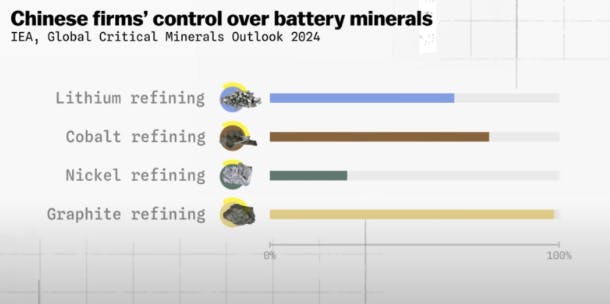

China’s relatively lenient environmental regulations and low labor costs have enabled it to control the majority of mineral processing, accounting for an estimated 92% of total global processing capacity. The country controls 70-95% of global refining and processing for critical minerals: 70% of lithium, 78% of cobalt, 68% of nickel, 95% of graphite, and 91% of rare earth elements. In graphite alone — the sole critical mineral used for anodes in batteries — China is responsible for over 80% of the mining and over 90% of the refining. For LFP batteries, China produces 75% of the phosphoric acid needed for production and 95% of the high-purity manganese sulfate.

Source: Vox

This means that car manufacturers obtaining minerals from operations outside China still need to go through Chinese factories. One Chinese EV expert, John Helveston at George Washington University, said of this dynamic, “The biggest factor for China is that they control all the upstream material supply chain.” Even if an EV battery is built in a plant in the US, “the raw materials for that are being processed and refined in China first. It’s the same starting point everywhere.” The US, on the other hand, imports over 95% of rare earth elements from China as of December 2025, and is 100% dependent on imports for refined nickel products and battery-grade manganese sulphate. China’s mineral refineries take two to five years to build. In comparison, Australia’s first lithium refinery, approved in 2016, did not produce lithium until 2022, six years later.

Manufacturing Batteries

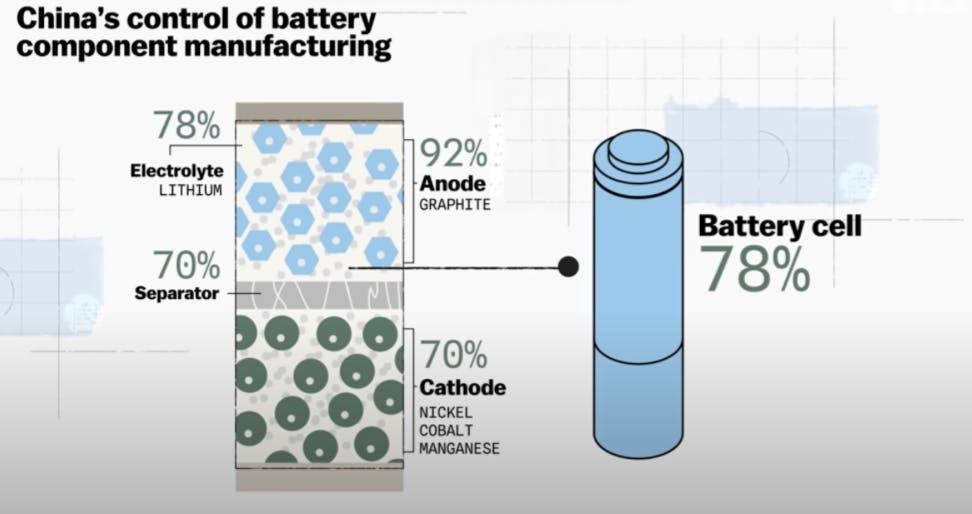

After minerals are refined and concentrated, battery assembly consists of a process through which the cathode and anode components are attached to metal sheets thinner than the width of a human hair, stacked on separators, wetted with electrolytes, and rolled into battery cells. Roughly 40% of electric vehicle costs come from its battery, making control of battery production and inputs a critical factor in achieving lower costs.

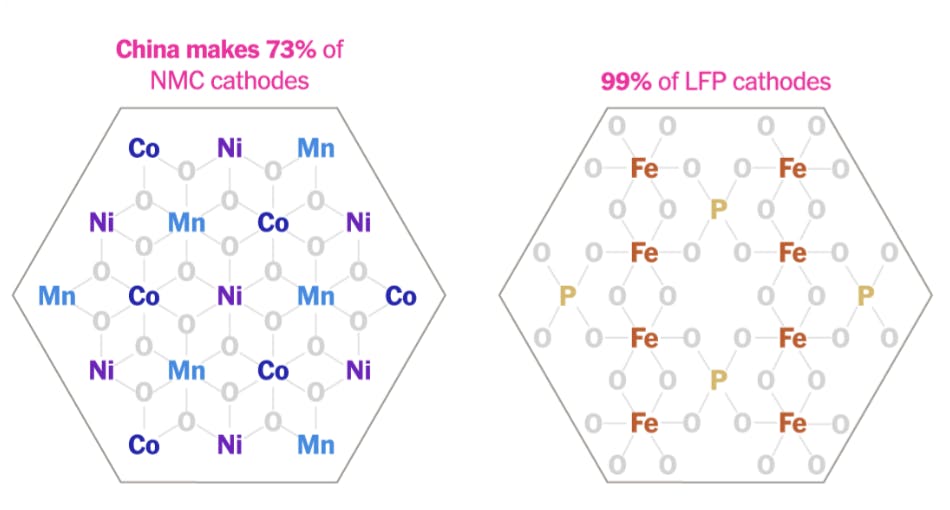

China’s dominance in battery manufacturing is overwhelming: 85% of global battery cell manufacturing capacity is located in China, and more than 70% of all EV batteries ever manufactured have been produced in China. China’s mineral dominance translates to control of 78% of battery electrolytes (the top four electrolyte producers in the world are Chinese), 92% of the anodes, 70% of the separators, and 70% of the cathodes.

Source: Vox

Chinese companies like Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited (CATL), the world’s largest battery maker, maintain institutional knowledge and centralized expertise that help them continue to innovate in battery manufacturing. Companies like BYD benefit from vertical integration: originally a battery manufacturer for electronics, the company acquired a struggling car factory in 2003 and pivoted to electric cars. In 2025, BYD will own most of its battery supply chain, enabling the company to drive down costs for its vehicle models. Its innovation has allowed the company to pack blade-light batteries at a higher density in its vehicles.

Source: SNE Research

Chinese companies have prioritized lithium-iron phosphate (LFP) battery chemistry. LFP batteries differ from traditional lithium-ion batteries by using a phosphate cathode instead of a cobalt-nickel cathode, making them safer and longer-lasting, though their energy storage capacity is lower for the same volumes. Though LFPs were initially deemed unsuitable for EVs due to their low energy density, Chinese researchers have lowered the costs of LFP batteries by 30% and honed them for capacity.

Source: New York Times

Given the density of battery manufacturing companies in China and subsidies provided by the Chinese government for battery manufacturing materials, Chinese batteries can be manufactured and sold at low prices relative to other manufacturers. Prices for lithium-ion batteries dropped 20% in 2024, with the fastest declines in China, where they fell nearly 30%. This further widened the gap between battery prices in China against the rest of the world. Though the Chinese government has recently denounced the “involution” of slashing battery prices, prices are still expected to go down. China can also build battery factories at half the cost of North American countries, enabling competitive future expansion.

Vertical Integration

Vertical supply chain integration has allowed Chinese EV makers like BYD to produce almost all EV inputs in-house, including batteries as well as specialized parts like chips and motors. Eric Luo, vice-president of LONGi Green Energy Technology, described the set-up as “cluster manufacturing,” saying, “there are places where, within a three- to four-hour drive, you can have everything… There’s nowhere else globally where you can have all that innovation clustered together”, referring to components, manufacturing technology, and the requisite workforce.

Robin Zeng, CATL’s founder, said that it costs six times as much to build a factory in the US as in China. Many times, the factories for each component are in close proximity to one another, speeding up production. While Western automakers take three to four years from concept to production, BYD takes less than 24 months. Some Chinese automakers can design and produce new models in just six months.

Charging Stations & Infrastructure

Beyond batteries and EVs, China has also ramped up infrastructure investments, enabling EV use throughout the country. The Chinese government treats EV charging stations as crucial infrastructure, similar to US-mandated highway maintenance. In its public announcements, the Chinese government committed to creating a “10 vertical, 10 horizontal, 2 ring” highway of fast charging networks. The near-term goals (2024-2025) of the Chinese government include 60% of charging occurring near off-peak hours in pilot cities, while medium-term targets (2030) are high-quality charging infrastructure competition.

Source: ResearchGate

The Chinese government declared in 2024 that in urban cities, the EV charging coverage should be more than 80% of tier-1 cities, with 65% of highway service areas equipped with charging facilities. The standards for this coverage include smart charging systems integration, unified national charging standards, and interpretability resources. The declaration further established a smart connected vehicle initiative in which the pilot program from 2024-2026 will focus on 5G network full coverage in pilot areas, 90% of traffic signal connectivity, and at least 10 automated parking facilities.

Even in rural places, every county requires EV charging coverage for integration with rural tourism under the 2024 declaration. Another rural market development scheme outlined specific policies to penetrate rural markets, with local consumption vouchers for rural residents, trade-in programs for low-speed electric vehicles, and technical training for maintenance personnel.

Car Technology

Chinese EV companies such as BYD, Xpeng, and Xiaomi include advanced features like autonomous driving, voice recognition, and in-car AI assistants as part of their standard vehicles. The “God Eye” driver assistance program, one such advanced feature, enables BYD vehicles to navigate congested and chaotic Chinese roads, even when other drivers violate traffic laws.

BYD recently debuted a model that can recharge itself in just five minutes, drastically eliminating the barriers to EV adoption. Certain BYD cars are equipped with drones that can take off and film footage, others can “dance” to different tunes and bounce up and down (as American streamer iShowSpeed experienced). Others have rear seats that recline into beds, on-screen video games, and magic air suspension. Some Chinese EVs also include rotating touchscreens that can auto-swivel between landscape and portrait, guitar-like strings on door panels, a gear-selector inspired by a rocket ship, and cars that can “tank turn” on the spot by spinning their wheels in different directions. Videos of Chinese cars in “floating” mode can be found on X navigating bumpy terrain.

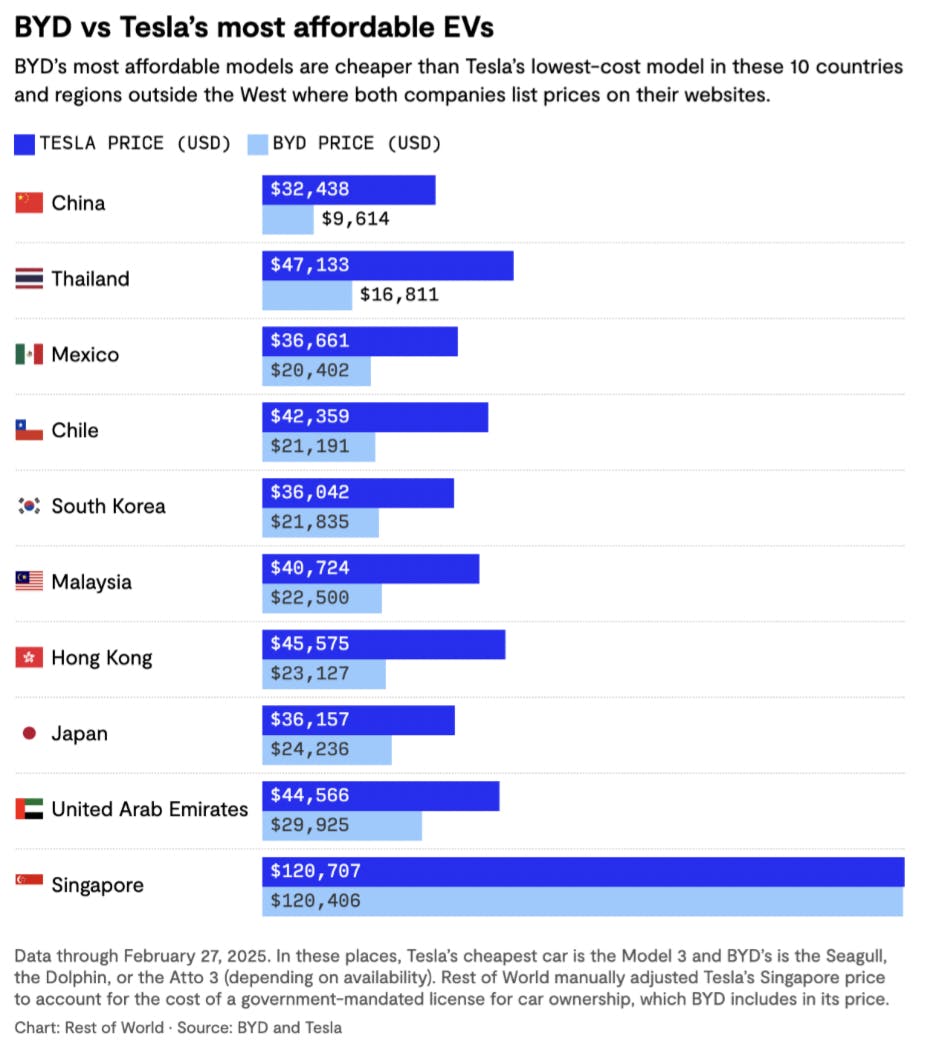

Ford CEO Jim Farley said of Chinese EVs, “They have far superior in-vehicle technology. Huawei and Xiaomi are in every car… You get in, you don't have to pair your phone. Automatically, your whole digital life is mirrored in the car.” More importantly, these luxury-branded cars are affordable compared to foreign alternatives like Teslas. As of 2025, Tesla’s cheapest car is the Model 3 (over $36K for the base model), while BYD’s cheapest cars are the Seagull ($8K) and Dolphin (under $14K. In most countries around the world without tariffs, a BYD model is around half the price of a Tesla.

A Tesla Model Y costs around $45K. In comparison, a BYD Tang is around $11K, Xpeng G6 (which has almost identical features to Model Y) is at $27K, and Li Auto L6 is in a similar price range as Model Y but with an 893-mile range (Model Y has around 350 miles). Even in Europe, with the tariffs, consumers can obtain an entry-level BYD for under €30K. In May 2025, BYD slashed its price again, with its cheapest model, Seagull, costing only $7.7K. Though it is unclear whether the price squeeze is sustainable, Chinese EVs still offer significant cost savings compared to Tesla.

Source: Rest of the World

China’s Path to EV Dominance

In the early 2000s, China lagged behind automakers in Japan, Germany, and the US in automobile output. Though China manufactured internal combustion engines en masse, it was not a major producer of finished automobiles. In 2025, however, over 60% of the world’s electric cars will be produced in China, and the Ford CEO regularly visits China to learn from companies. How did America lose its dominance to China in less than thirty years?

Timeline of Government Subsidies & Industrial Policy

In 2001, the Chinese government introduced EV technology as a priority science research project in its Five-Year Plan, the country’s highest-level economic blueprint. As of December 2025, the Chinese government website maintains a list of priorities related to electric vehicles, with one title published in August 2025 titled “With the Final Battle of the 14th Five-year Plan | Leap Forward: Our Country’s New Energy Vehicle Industry Accelerates Quality Improvement and Shifts to the New Era.” The article said, “Developing new energy vehicles is the only way for our country to move from an automobile power to an automobile powerhouse.”

In 2009, China began granting financial subsidies to EV companies producing buses, cars, and taxis. Less than 500 EVs were sold in China that year. In 2010, the government designated five cities (Shanghai, Shenzhen, Hangzhou, Hefei, and ChangChun) as testing spots for the rollout of electric vehicles that were heavily subsidized. The same year, the “Ten Cities, Ten Thousand Vehicles” initiative subsidized new electric and hybrid vehicles in public transport sectors like buses and taxis. Shenzhen later became the first city in the world to completely electrify its public bus fleet. The millions of public transits, buses, and taxis in China also provided reliable contracts and a revenue stream for lots of vehicles. Ilaria Mazzocco, a senior fellow in Chinese business and economics at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said, “In addition to the financial element, it also provided a lot of [road test] data for these companies.”

In 2017, the government began giving out green car plates to electric cars. EVs received preferential treatment with free two-hour parking and free delivery passes in certain cities. A year later, in highly populated cities like Beijing and Shenzhen, EVs no longer needed to lottery for plate numbers. License plates that once required waiting nearly a decade or paying thousands of dollars could be procured for free with the purchase of an EV.

In 2018, the standards for battery and vehicle subsidies increased, allowing only cars with ranges further than 300km to qualify for subsidies. Despite these changes, government support was equivalent to almost a third of the sector’s total revenue in 2019.

From 2009 to 2022, the Chinese government invested more than $29 billion into subsidies, R&D, and tax breaks. Some of these subsidies were also offered for foreign brands like Tesla, which set up a factory in Shanghai in 2018. “To go from effectively a dirt field to job one in about a year is unprecedented,” Tu Le, managing director of Sino Auto Insights, said. “It points to the central government, and particularly the Shanghai government, breaking down any barriers or roadblocks to get Tesla to that point.” The success of Tesla’s Shanghai facility created a “catfish effect” in which some Chinese brands attempted to innovate and catch up with Tesla (many copied from Tesla’s open-sourced patents).

The government replaced the official subsidy policy with a “dual credits” system in 2023, where companies with surplus new energy vehicles can sell them to companies that face penalties for selling non-compliant vehicles. The government is predicted to waive some $97 billion in tax exemptions for the EV industry through 2027.

Industrial Base, Clusters, and Talent

The entire EV industry received a regulatory boost in 2007 when Wan Gang, a former auto engineer for Audi, became the Minister of Science and Technology in 2007. Dubbed the “father of China’s electric car industry,” he was a major proponent of EVs and tested Tesla’s Roadster model in 2008, the year it was released.

As of December 2025, China has nearly 50 graduate programs focused on battery chemistry and metallurgy. 66% of widely cited papers on battery technology come from researchers in China, compared to 12% coming from the US. BYD employs around 120K engineers, equivalent to Tesla’s entire labor force.

Tariffs

China has faced multiple tariffs from Western countries in response to its critical control of raw materials. In 2024, the European Union imposed duties on Chinese electric car imports, while the US and Canada implemented tariffs exceeding 100% the same year. Chinese lithium-ion EV batteries also face a 25% tariff from the United States, while critical minerals from China (lithium, graphite, magnets) also face a 25% tariff. Chinese graphite, one of the only minerals produced domestically in China, faces tariffs of around 93% in the US. As of December 2025, US consumers have to pay a 250% tariff (when adding all other tariffs costs non-specific to EVs) to buy a Chinese EV, effectively erasing BYD’s price advantage relative to US EVs.

Similarly, Mexico and Brazil approved tariff hikes after experiencing a surge in Chinese EVs. Despite these obstacles, Chinese companies have continued exporting vehicles across the globe. In Europe, exporters have sold to countries like Spain and Italy, which are less economically tied to German carmakers. To avoid tariffs, more of these cars are hybrid and gasoline cars, exempt from the scrutiny, inadvertently offering a dirtier solution than fully electric cars.

Tightening trade restrictions are also pushing Chinese manufacturer to expand their overseas footprint. In Chinese-friendly countries like Hungary, Turkey, and Brazil, BYD has also set up electric European car product plants. By 2026, Chinese overseas manufacturing capacity is expected to almost double to reach 4.3 million vehicles per year. The overseas expansion of Chinese producers, prompted by tariffs, helped drive sales in emerging markets in Latin America and Europe.

Chinese Retaliation and Restricting Exports

In response to international tariffs, China has tightened its chokehold over its mineral supply chain. In July 2025, the Chinese government announced that it would restrict efforts to transfer China’s eight key EV battery manufacturing technologies out of the US. Export of battery cathode, LFP technology, and others was restricted. Rare earth metal exports were also highly restricted, though China recently began issuing export licenses for some of these metals in July 2025.

US Capacity

The US government and auto-manufacturing industry have contributed to advancing innovation in EV manufacturing towards competing with China in the future. In 2025, US battery manufacturing capacity has doubled since 2022 following the implementation of tax credits for producers. In March 2025, the government issued an executive order titled "Immediate Measures to Increase American Mineral Production” to expedite permitting and increase domestic investment in critical mineral projects. Specifics include broadening the definition of critical minerals, prioritizing federal lands for mining, and leasing authorities to facilitate rapid development and investment in domestic mineral projects. Many of these projects are likely to face public scrutiny due to environmental regulations.

While the Inflation Reduction Act once offered subsidies for US consumers purchasing EVs up to $75K, it has since been rolled back under the Trump administration. The politicization of EV has made long-term change difficult to sustain. While the Democratic Party champions clean energy and EVs in general, it opposes many of the mineral extraction plans necessary to reduce Chinese reliance. At the same time, the Republican Party rolled back IRA benefits that supported domestic EV demand, but advocates for American rare earth mineral factories. While Chinese government officials are highly encouraged to use electric vehicles, US politicians have the opportunity to target government purchasers, such as the U.S. Postal Service, the Transportation System, and other agencies buying EVs, to increase demand.

To pose a challenge to the Chinese EV market, the US government will also likely need to subsidize and support domestic manufacturers and innovation. Specifically, analysts have suggested the US increase R&D funding through the NSF, Department of Energy, ARPA-E, and Department of Defense. The US will likely need to develop an ultra-energy-dense, cheap battery for long-distance travel, and increase battery production by closing the gap between university research and mass production incentives.

Chinese Outlook

While China currently dominates EV production, it is not clear if its growth is sustainable. Fierce domestic competition has led to price-cutting in Chinese automakers and suppliers. There are over 50 automakers fighting for customers by “involution,” or cutting prices repeatedly. In September 2025, BYD said that its profits fell by almost a third in the spring compared to 2024 due to price competition. In 2020, Chinese EV maker Nio faced near-bankruptcy, and was only made solvent when the Anhui provincial government gave the company a $1 billion investment with a 25% stake in the company. While the race to the bottom helps consumers, it hinders long-term growth. The May 2025 announcement from the Chinese government to stop price wars puts the industry in a double bind: they can either continue producing cheap, affordable cars for the average consumers or increase their prices and face fierce resistance from consumers both within the country and outside.

China currently has the capacity to produce twice as many cars as it sells domestically annually. There are certain parking lots in China where new EVs are stored outdoors in large quantities, waiting to be sold. As consumer appetite slows for EVs, China needs to find new ways to sell its products in a global market that aims to compete with it.