Actionable Summary

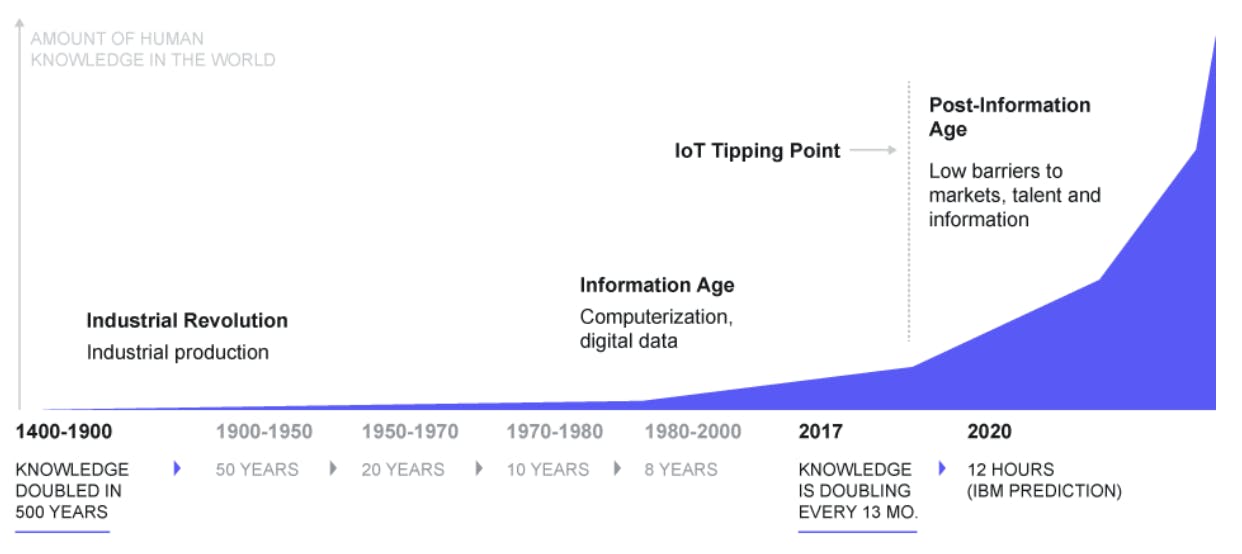

The total amount of human knowledge was doubling at a rate of once every 100 years until 1900. It has been doubling every 13 months more recently. As the volume of information continues to grow, the need for effective knowledge management becomes increasingly urgent.

The idea of a second brain or "extended mind" can be traced back to the common practice of note-taking and journaling, which have long been used to supplement our memory and facilitate the creative process.

Today, “second brain” is a term used to describe tools that allow users to capture, store, and retrieve information on demand.

Using a second brain allows users to hand over the job of noting and remembering to an external system so they can focus on doing creative work and moving the needle.

Second brains today either take the form of pen and paper, handwritten notes with index cards, or a stack of personal knowledge management (PKM) tools like Apple Notes, Notion, Mem.ai, Roam Research, and Obsidian. These tools allow users to tag and link notes together.

PKM tools today typically involve three distinct components: (1) Information capture: digesting information from multiple sources; (2) Information storage: linking thoughts with tags and extracting core takeaways from a given resource; (3) Information retrieval: drawing on inspiration across domains and putting insights into action.

Traditional PKM tools are static. They become cluttered and unmanageable, leading to lost insights and missed opportunities for creative thinking. With this model, users learn something → write it down → forget about it.

Rapid advancements in AI and natural language processing, coupled with the explosive adoption of tools like ChatGPT, have laid the groundwork for a solution capable of revolutionizing the way we capture, store, and retrieve knowledge.

In contrast to a static second brain, an AI-powered second brain would enable dynamic retrieval, adapting to the user's needs and presenting relevant information based on context and current tasks.

As human intelligence and AI continue to converge, we may witness the development of more advanced hardware and software integrations, such as Neuralink and other brain-computer interfaces. These innovations could further enhance the capabilities of a second brain, providing direct access to knowledge repositories and even allowing for real-time communication between humans and AI.

It is possible to create a manual second brain right now to help avoid information overload. But the future of an AI-powered second brain will begin with the emergence of a true copilot for the human mind.

The Problem of Information Overload

“The mind is not a vessel to be filled, but a fire to be kindled.” (Plutarch, On Listening to Lectures)

Since the beginning of the internet and the proliferation of social media, people have been increasingly bombarded with news, articles, and data, all competing for finite attention. Information overload and digital clutter can prove overwhelming and limit people’s ability to think clearly and creatively.

The human brain, although an incredible tool for generating ideas and solving complex problems, is ill-equipped to manage such a deluge of data. As a result, it often struggles to retain and make sense of overabundant information. The volume of information is reaching such a volume that just being selective about what you consume is no longer an effective solution. At such great velocities of new information, distinguishing signal from noise is becoming an impossible task for any unaided human mind.

Source: Valamis

Advancements in the storage of knowledge have been a driving force of human progress throughout history. The invention of the printing press in 1448 ushered in a new age of mass communication and helped contribute to the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment. The creation and spread of knowledge via the printing press also raised literacy levels worldwide.

The "knowledge-doubling curve" is a theory that describes the rate at which human knowledge is increasing over time. The concept of the knowledge-doubling curve was first proposed by Buckminster Fuller, a notable futurist, in the 1980s. At that time, Fuller estimated that human knowledge reached a doubling of once every 100 years in 1900, a rate which accelerated to once every 25 years by 1945 and has continued to accelerate since.

Compounding knowledge has allowed humanity to expand and thrive. Nonetheless, its rapid growth also implies that old knowledge is becoming obsolete more quickly than ever. The “half-life of knowledge”, a term coined by Austrian-American economist Fritz Machlup in 1962, refers to the time elapsed before half of the knowledge in a given field is superseded or becomes obsolete. As Alvin Toffler, a futurist and the author of the 1970 book Future Shock, put it:

“The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.”

Toffler argued that transitioning from agrarian to industrial society was a revolution that caused structural changes, leaving people disconnected and subject to "future shock.” He suggested this could lead to numerous social issues including "information overload,” a phrase he helped popularize.

The massive influx of new knowledge and the declining half-life of knowledge creates a tough challenge: sifting out the useful information from the obsolete. As the volume of data surges, the capacity to effectively sift through and analyze this information becomes a crucial skill. This capacity can be compared to the cognitive strategies employed by grandmaster chess players, who use "chunking" to rapidly identify relevant patterns, achieving a depth of analysis and speed advantage over amateurs. Chunking is the process by which the mind divides large pieces of information into smaller units (chunks) that are easier to retain in short-term memory. Chess masters store many chess patterns, known as "chunks,” in their memory. They can recall these patterns and associated plans and ideas to aid their performance as they play a chess game.

The efficient synthesis of information enhances accuracy and expedites decision-making, ultimately leading to a compounding effect of small advantages in information processing. Therefore, individuals who can combine relevant information in a timely manner are better equipped to capitalize on opportunities and navigate the Information Age, a period of human history marked by the transition from industrial production to information technology as a core driver of the economy. As E.O. Wilson, an American biologist, in his book ‘Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge’, wrote:

“We are drowning in information while starving for wisdom. The world henceforth will be run by synthesizers, people able to put together the right information at the right time, think critically about it, and make important choices wisely.”

As Wilson states, good decisions can only be made when we have the right information at the right time. Yet with our cognitive resources stretched thin, we must find alternative means of managing the information we consume to unlock our true creative potential when needed.

Enter the concept of the “second brain” — a digital extension of our mind that captures, organizes, and synthesizes information on our behalf. A second brain lets us focus on what truly matters: generating new ideas and making informed decisions without having to rely excessively on hard-to-master tools like “chunking”.

The Evolution of Note-Taking

Note-taking has undergone a significant transformation from ancient times to the modern digital age. The evolution from analog methods to digital applications reflects our changing understanding of information organization and knowledge retention.

Socrates famously criticized writing as a degradation of memory, but this claim did not bear out over time. In the days when literacy was scarce and writing had to be done laboriously by hand, note-taking was a precise and meticulous task carried out by scribes who documented what someone said exactly as they said it. This note-taking method is reflected in the preservation of Aristotle's lecture notes. These notes have been passed down over centuries, providing invaluable insights into the philosophical ideas of the time. This meticulous approach was the source of Socrates’s criticism that writing was more mimicry than understanding. Individuals learn to repeat content without critically engaging with it.

After the advent of mass printinge, people began to take notes in the margins of books and documents. This process required the organization and categorization of the information, and it wasn't long before personal notebooks became a widespread phenomenon. Contrary to Socrates's prediction, humans found they could accomplish more by taking better notes. Rather than simply mimicking phrases, note-taking allowed people to organize larger corpuses of information leading to an increased ability to make new connections and retain learning. The concept of the "extended mind" helps explain this phenomenon. The extended mind thesis posits that developing processes for recalling information is more efficient than memorizing it, expanding one's cognitive ability. The phone in your pocket has not made you worse at information processing; rather, it has helped outsource some of the constraining aspects of information storage and retention, expanding overall cognitive ability.

The advent of digital technology has ushered in a new era of note-taking, transforming it from a strategic task to an accumulative one. Modern note-taking applications like Notion, Mem.ai, or Roam Research aim to organize and manage information efficiently. While these tools help us better store and manage information, we still have to find ways to recall and retrieve that information effectively.

One way to avoid lost thoughts is by ‘linking your thinking’. Proposed by personal knowledge management creator Nick Milo, the crux of this method is that linking your thoughts gives you a better chance of remembering information that you’ve encountered before and written down. Some common tools for this kind of linked thinking include applications like Roam Research or Obsidian organize users’ notes into a networked knowledge graph.

By constructing a series of interlinked notes, you can find common themes between your memories, increasing your ability to recall. This means your notes grow in value over time as you add new experiences and connections, enhancing your existing knowledge base. Roam Research has also productized the idea of a knowledge graph by allowing users to visualize and explore relationships between different pieces of information. Roam Research’s thesis about connections has been seen in other applications that have adopted hashtags as knowledge graph markers. By tagging notes with relevant hashtags in applications such as Apple Notes, users can quickly categorize and filter content, making it easier to retrieve and reference in the future.

The development of digital note-taking applications reflects a broader shift in how we approach knowledge management. From the precise documentation of scribes to the interconnectivity of modern graph-based systems, the evolution of note-taking mirrors our changing relationship with knowledge itself. Modern note-taking practices suggest that we have the capacity to extend our minds beyond the limitations of memory alone.

The civilizational impact of knowledge management’s transformation is hard to overstate. For example, media theorist Marshall McLuhan has argued that human epochs are defined by the technologies that produce and distribute information, with the character of these technologies defining the civilizations around them.

The Components of a Second Brain

“We are all plugged into an infinite stream of data, updated continuously and delivered at light speed via a network of intelligent devices, embedded in every corner of our lives. Value has shifted from the output of our muscles to the output of our brains. Our knowledge is now our most important asset and the ability to deploy our attention is our most valuable skill. Our challenge isn’t to acquire more information, it's to change how we interact with information, requiring a change in how we think.” (Tiago Forte, Building a Second Brain)

In the book “Getting Things Done,” David Allen said: "Your mind is for having ideas, not holding them." While the human mind is a remarkable instrument capable of generating innovative ideas, it possesses limited working memory, which makes it difficult to juggle multiple concepts simultaneously. Furthermore, long-term memory is susceptible to decay and distortion, causing us to forget or misremember important details. This inherent constraint hampers our ability to put the vast amounts of information we consume into action.

Second brains today take the form of either handwritten notes with index cards or a software stack of note-taking tools, allowing you to tag and link your notes together. This concept is not new; it can be traced back to the common practice of note-taking and journaling, which have long been used to supplement our memory and facilitate the creative process. Even so, most knowledge workers rely on their minds to do all the hard work. An individual’s manual second brain follows three distinct steps:

Information Capture. A second brain digests information from a multitude of sources. These include notes, emails, documents, conversations and media. The objective of the capture process is to take in anything interesting that can bring you future value, whether personally or professionally.

Information Storage. You—the human—now have to synthesize what you captured. This means extracting core takeaways from the website you saved or pulling out the nugget from the podcast you listened to.

Information Retrieval. You want to avoid your insights collecting digital dust. Revisiting notes inside your second brain to update and repurpose across domains regularly is important. The objective here is to put your insights into action.

While spreadsheets, databases and analytics tools help to some degree with this process, they are limited in their ability to consolidate and surface insights. Subsequently, information and skill-building for individuals and companies remain stored only in people's minds.

Synthesis of information is currently done manually. If I wanted to write a blog article on the philosopher Marcus Aurelius, I’d have to sift through all my notes and memories. This process is currently relatively disjointed, involving a large degree of context switching. The inspiration I would want to draw on often comes from multiple sources (handwritten notes in my journal, my writing in Notion, Apple notes, websites, YouTube videos, etc.) Pulling this information together is incredibly time-consuming, and data can be lost.

The Limits of Human Knowledge Management

As the speed of information increases, note-taking that is limited to an organization becomes more burdensome. Gone are the days of slowly reading a book to learn all about a topic; information comes fast and is often forgotten immediately. Modern knowledge work requires a high degree of responsiveness to the increasing speed at which information is produced and travels.

Inundated with information, meticulous notetakers often produce copious amounts of abstracted information that are never recalled. One reason for this is that the tooling they use exhibits a tradeoff between simplicity and power, which makes information harder to process as it accelerates, increasing the cost of management.

The limitations of current knowledge management systems can be bucketed into three major categories:

Alignment: Information is dynamic and context-dependent. Its usefulness and relevance are often determined by its alignment with specific tasks or objectives. While taking notes or capturing information, it can be challenging to determine the context in which that information will be most valuable. This misalignment can lead to notes that, when revisited, lack a clear purpose or fail to provide meaningful insights. For instance, a note jotted down during a meeting may seem significant at the moment, but may lose its significance when reviewed in isolation. Users are left with deciphering and relating notes to their current needs — an endeavor that can be time-consuming and cumbersome.

Labor Intensity: Effective note-taking and knowledge management often demand active engagement and effort. Users must consciously take notes, store relevant quotes or links, and organize the collected information meaningfully. This labor intensity can be a deterrent for some, resulting in missed opportunities to capture valuable knowledge. Furthermore, the onus of manually categorizing and tagging information can add to cognitive load, leaving users overwhelmed and potentially reducing the efficiency of knowledge retrieval.

Fragmentation: The advent of knowledge graph-based tools like Roam Research has changed the way users connect and associate information. However, even these sophisticated knowledge graphs are not immune to the challenge of fragmentation. While users can create associations and links between notes and concepts, making sense of the intricate web of connections still requires active engagement. Users must review and analyze these connections regularly to derive insights and identify patterns. This often leads to a network of unexplored associations as users struggle to find the time and energy to analyze and reflect on the vast landscape of interconnected knowledge.

The explosion of information available to each of us is demonstrating the cracks in our current processes for accepting, synthesizing, and acting on information. But AI is inaugurating a new information paradigm that the technology is best suited to assist with creating new content from existing information.

Why AI is the Solution

Traditional approaches to information retrieval tend to be static. We have to tag, link, and update our knowledge base ourselves. The hardest part is finding your insights on demand. Search is a useful tool but relies on one thing we want to escape: the limits of the human mind. It’s up to us to recall the information we want to retrieve (from our second brain), find it, and implement it.

By contrast, an AI-powered second brain would enable dynamic retrieval, adapting to the user's needs and presenting relevant information based on context and current tasks. Coveo, the AI-powered enterprise search tool, showed that knowledge workers spend an average of 3.6 hours searching for information each day, highlighting the inefficiency of conventional methods. By employing dynamic retrieval, the time spent on information search can be dramatically reduced, allowing knowledge workers to devote more energy to creative problem-solving.

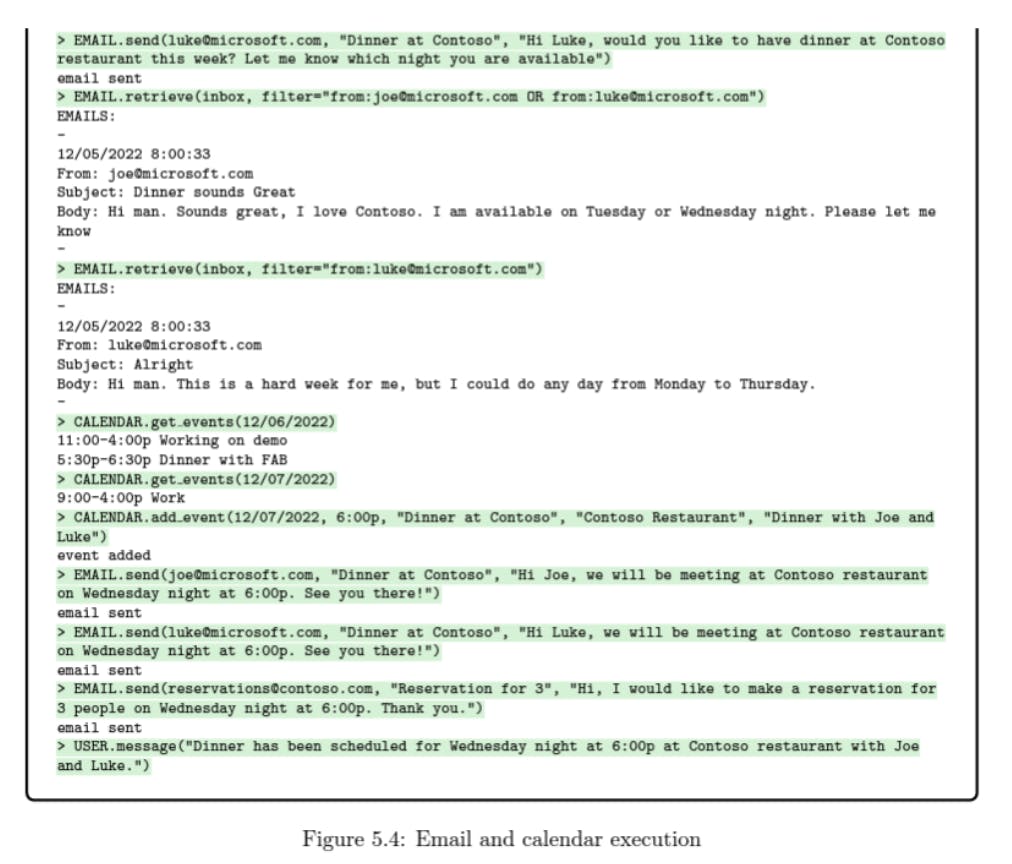

Moreover, an AI-powered second brain that can connect with other tools, such as email clients, project management software, and communication platforms, would be able to create a unified and comprehensive knowledge ecosystem. Interoperability would allow for seamless integration with a wide range of applications and platforms. For example, OpenAI’s GPT-4 can use multiple tools at once. It retrieves information about a user’s calendar, coordinates with others over email, books a dinner reservation, and then messages details to the users. Interoperability will be critical to ensure an AI-powered second brain becomes a truly integrated part of our daily lives, rather than just a standalone static tool.

Source: Microsoft Research

“Sparks of AGI,” a paper released by Microsoft Research in March 2023, highlights the possibilities of this interconnectivity. In it, the researchers made a case for how GPT-4 and Google’s PaLM were among a new generation of AI models exhibiting greater levels of general intelligence than before. They demonstrated GPT-4's ability to solve tasks across mathematics, coding, vision, medicine, law, psychology, and more without special prompting. They also found that GPT-4’s performance was often close to or even surpassed human-level, and exceeded prior models like ChatGPT. The researchers viewed GPT-4 as an early version of artificial general intelligence (AGI), having investigated its limitations and considered the societal impacts of GPT-4.

Moreover, in April 2023 developers were creating "autonomous agents" powered by LLMs to tackle challenging tasks. These agents could become a breakthrough in the effective use of LLMs if successful. Interacting with an LLM typically requires us to type in specific prompts until we achieve the desired output. However, crafting many prompts to answer a complex question can be time-consuming. To automate this process, developers have created autonomous agents. Autonomous agents can generate a sequence of tasks to fulfill a predetermined objective. Agents can perform various duties such as web research, coding, and making to-do lists. They provide a software interface to large language models and use common software practices like loops and functions to guide the LLM in achieving goals.

Leveraging Recent LLM Advancements

Since ChatGPT's debut in late November 2022, AI has shown that it can change the way that knowledge workers tackle daily tasks. Critical in distinguishing AI tools that successfully augment knowledge work is a focus on user experience. For instance, OpenAI released its ‘Playground’ in 2021. This web-based tool makes it easy to test prompts and familiarize yourself with how the language model works. Yet OpenAI’s GPT playground didn’t go viral. ChatGPT, on the other hand, did because user experience allows the masses to understand the power of AI. While the underlying technology is similar, the user interface is different. OpenAI layered a known interface — chat— on top of its language model, opening up the realm of usability for everyone to understand.

A knowledge worker’s second brain must be able to capture, synthesize and retrieve information at the speed of thought. It’s important to remember that large language models (LLMs) like GPT-4 are autoregressive. They are next-word prediction models that forecast future values based on past values. While AI can produce coherent text generation, it struggles with complex problems.

We can break complex problems down into two types of intellectual tasks. Incremental tasks (which GPT-4 is great at) and discontinuous tasks (which GPT-4 is bad at).

Incremental tasks:

Solved sequentially or gradually.

Progress made by adding one word or sentence at a time.

Examples: writing summaries, answering factual questions, composing poems.

Discontinuous tasks:

Require a creative leap in progress.

Involves discovering new ways to frame problems.

Examples: writing jokes, developing scientific hypotheses or new writing styles.

To the layman, asking AI to tell a joke or solve a math problem often leads to disappointment and the immediate berating of said language model: “I can do better than this” or “computers aren’t so smart after all”. But when it comes to taking a lot of information (like what a user would have in their notes) and making incremental connections between those ideas, AI could potentially be exceptional at that activity.

Applications like Notion, Mem.ai, and Roam Research are now using AI integrations to uplift knowledge bases. Most recently, Notion has incorporated OpenAI’s LLM to offer AI assistance to its users. Notion AI is a helpful tool to assist users in the writing process. It can help users brainstorm, edit, summarize, etc., and is an additional resource to manage time effectively. Notion AI can help users craft their first draft by providing ideas on any subject, enabling them to be more creative in their writing. It can also detect and correct spelling and grammar mistakes and translate posts into different languages. Additionally, Notion AI can summarize and extract the main points from meeting notes.

It is only when we switch our perspective from LLMs as a text-generation tool to a thinking engine that the value of AI increases in promising directions. Our knowledge base will increase in value when we augment it with AI and connect it to applications within our digital ecosystem. Machine learning systems have historically promised to relieve us of mundane tasks so that we can focus on creativity, empathy, communication, and problem-solving. However, powerful language models are now working in reverse, outsourcing human creative and analytical thought. We are already seeing applications such as producing realistic artwork, interpreting unstructured data, and offering intelligent code recommendations to software engineers.

What’s more, the value of this relationship will grow with the more information that is stored. Therefore, AI can actively assist in the creative process by suggesting new perspectives, identifying gaps in our understanding, and connecting seemingly unrelated pieces of information. This symbiotic relationship between humans and machines should allow us to harness the full power of our collective knowledge, resulting in heightened output and creativity. This could be augmented further when we add feedback loops, which could market the transition from the augmentation of knowledge worker tasks to the automation of knowledge worker tasks inside your second brain.

The AI-Powered Knowledge Worker

As AI continues to evolve and permeate various aspects of our lives, the future of note-taking promises to be significantly more efficient and intuitive. Advanced natural language processing, voice recognition, and machine learning algorithms will allow for the automatic generation, organization, and summarization of notes, transforming the way we capture and interact with information. Furthermore, integrating augmented reality and virtual assistants into note-taking will create an interactive and immersive experience that transcends traditional boundaries.

The AI-enabled knowledge worker can expect marked improvements in efficiency and productivity as a result of streamlined information management. By automating mundane tasks such as data entry, sorting, and categorization, AI frees up valuable time and mental bandwidth, allowing knowledge workers to focus on more meaningful endeavors. As of 2023, this increased productivity is expected to raise global GDP by 7% in the coming decade.

Operating with an AI-powered second brain will inevitably change your biological brain. We must learn to adapt our thinking to the presence of a technological appendage. This may involve refining our ability to ask probing questions, identify relevant patterns, and draw connections between disparate ideas. By nurturing these skills — in tandem with developing the underlying technology — we can ensure that our partnership with our second brain remains fruitful and effective, pushing the boundaries of human knowledge.

The widespread adoption of the "second brain" can potentially transform the workplace and society. As we become more adept at harnessing the power of artificial intelligence to augment our cognitive abilities, we may witness a renaissance of innovation across diverse fields such as science, art, and education. A second brain offers a promising vision of a more enlightened, creative, and collaborative future by enabling us to effectively navigate the information age and tap into the full spectrum of human knowledge.

Brain-machine interfaces have been around for some time. Their earliest success was demonstrated in 2006 when BrainGate, developed at Brown University, enabled a paralyzed person to control a computer cursor. Research groups and companies, such as the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and DARPA-backed Synchron, have since continued the development of similar devices. These have two approaches: invasively, through an implant touching the brain as with Neuralink, or non-invasively, using electrodes near the skin as with now Meta-owned CTRL-Labs.

As AI and human intelligence continue to converge, we may witness the development of more advanced hardware and software integrations, such as Neuralink or neural chip implants. Neuralink provides a brain-computer interface consisting of thousands of electrodes implanted in the brain to read and send neural signals to a computer.

These innovations could further enhance the capabilities of a second brain, providing direct access to our knowledge repository and even allowing for real-time communication between humans and AI. Such advancements have the potential to completely change how we interact with information and redefine the nature of human intelligence and cognitive ability.

How AI-Enabled Second Brains Will Revive Innovation

In the future, the emergence of an AI-powered second brain as a singular system with integrations across people’s digital ecosystems will act as a true copilot for the mind. Rather than positing a particular solution to what an AI-powered second brain looks like, this research is intended to inspire future tool development by identifying an imminent area of opportunity.

Ultimately, we are at an inflection point. The explosion of personal knowledge management tools like Notion, Mem.ai, Obsidian, and Roam Research, coupled with AI language models now capable of superhuman feats, will enable us to more easily tap into our innate creativity. This will allow us to generate new ideas and insights that would otherwise remain buried beneath the avalanche of data that defines our modern lives, and could lead to a renaissance of innovation.

Special thanks to Ryan Khurana for research support.