In August 2025, the Trump administration announced a landmark deal to acquire a 10% equity stake in Intel, purchasing roughly 433 million newly issued shares for a total of $8.9 billion. This move represents the first major strategic shareholding by the US government in a leading technology company.

Unlike past episodes of federal intervention in the private sector, Intel was not facing imminent insolvency. Although Intel posted operating and net losses in Q2 2025 due to restructuring costs and impairment charges, the company still generated over $12 billion in revenue that quarter and, as of 2024, retained the second-largest global market share in semiconductor manufacturing. The equity purchase, therefore, reflects not an emergency rescue but a deliberate strategic choice and an acknowledgment that advanced semiconductor capacity itself is a national security asset.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) produces 92% of the world’s most advanced semiconductors, while the US share of global chip fabrication has collapsed from 100% in the 1960s to 37% by 1990 and just 8% by 2024. This decline reflected a long-standing and misguided belief that the US could lead in design while outsourcing fabrication to lower-cost overseas foundries. That logic has created a dependence on Taiwan that leaves critical sectors vulnerable to supply disruptions. Without reliable access to leading-edge chips, the West’s ability to sustain progress in AI and other strategic technologies would be at risk.

As the only US-based contender with the technical ability to rival Asian foundries, Intel’s capacity represents the closest foundation for a domestically controlled supply chain. The government’s decision to acquire a stake in Intel must therefore be seen not simply as a financial intervention, but as the first major step towards directly shoring up the nation’s technological self-sufficiency. America’s effective reliance on Taiwan for nearly all advanced chip production has made building an American TSMC a national imperative.

By taking a stake in a functioning technology leader, Washington is breaking from its historical pattern of involving itself in private industry only during wartime or financial crises. The move mirrors elements of China’s long-standing model of strategic state involvement, raising the possibility that the US could edge toward its own form of state capitalism. Whether this remains an exception or signals a broader shift, it nevertheless marks a turning point in how government and business power intersect.

History of US Government Involvement in the Private Sector

In 1917, President Woodrow Wilson nationalized the railroads under the US Railroad Administration to ensure that troop and materiel transport was centrally coordinated. The government directly operated the rail network until 1920. During World War II, intervention went further. The Defense Plant Corporation and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) financed or directly built thousands of facilities, from shipyards and aircraft factories to synthetic rubber plants, which were then leased to private operators. At its peak, more than 80% of RFC loans were tied to defense production.

Later episodes in American history reflected a pattern of reactive intervention in failing sectors. In the 1970s, after the collapse of several major Northeastern railroads, Washington created Conrail, a federally owned company that absorbed bankrupt freight lines until its privatization in 1987. Similarly, Amtrak was established in 1971 to take over unprofitable passenger routes abandoned by private carriers. At the time, Amtrak’s creation was widely seen as a temporary fix, destined to end with the broader collapse of passenger rail.

During the 2008 financial crisis, nationalization extended into the finance industry. That year, the Federal Housing Finance Agency placed mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac under conservatorship, where they effectively remain as of 2025, nearly two decades later. In 2008, the Treasury and Federal Reserve also took nearly an 80% equity stake in American International Group (AIG), one of the world’s largest insurers, to prevent systemic collapse.

In 2008, Congress authorized the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), which gave Treasury Department up to $700 billion to stabilize the financial system; about $443 billion was ultimately disbursed in loans, equity purchases, and guarantees to banks and automakers. In 2009, the government also injected roughly $50 billion into General Motors, taking a majority stake, while Chrysler underwent a government-managed restructuring.

These cases illustrate how US nationalizations typically arose under duress and rarely reflected a clear or lasting industrial strategy. These were not designed as long-term state holdings but as emergency backstops, combining equity stakes and subsidies to restore private market confidence as quickly as possible. Once the immediate problem was solved, Washington typically saw no need to maintain ownership, reflecting a broader US preference for private markets over permanent state control.

Unlike these past episodes of state intervention, the government’s stake in Intel is not meant as a temporary rescue or a bridge until private markets recover. Rather, the aim is to secure long-term domestic control over the supply chains that underpin artificial intelligence, advanced defense technologies, and critical infrastructure.

The Intel deal is not an isolated incident and may reflect a broader late-2025 trend under the US government of using direct equity stakes to secure strategic supply chains. ****In September 2025, the Trump administration announced plans to take a 10% equity stake in a major Canadian lithium miner supplying General Motors (GM), while in June, Washington acquired a golden share in US Steel as part of the company’s acquisition by Japan’s Nippon Steel. The Pentagon also purchased a 15% stake in MP Materials in July 2025, becoming the firm’s largest shareholder and securing a supply of rare earth minerals critical to advanced manufacturing and defense systems.

These moves point to the emergence of a new equity-based industrial policy, where government buy-ins are used not as temporary stopgaps but as tools for asserting long-term national interests. In doing so, Washington may be inaugurating a new era of proactive state ownership in key industries and redrawing the boundaries between public and private control of the economy.

How the US Identifies Strategic Industries

The United States employs a fragmented, multi-layered process to identify and support sectors deemed vital for national security and competitiveness. The process involves alignment between Congress, the executive branch, federal agencies, and state governments, who designate strategic industries through a mix of acts (like the CHIPS and Science Act), national security reports, and agency-level programs. As of 2025, priority sectors include semiconductors, batteries, critical minerals, advanced manufacturing, and energy storage.

Modern industrial selection typically operates through competitive grants (e.g., $52 billion in semiconductor subsidies via the CHIPS Act), tax incentives, and procurement. The Department of Defense’s Office of Strategic Capital (OSC) 2025 investment strategy outlines a tiered approach: controlling "chokepoints in economic networks" in the short-term, dominating key sectors in the medium-term (such as autonomous mobile robots and advanced bulk materials), and winning tech races in areas like synthetic biology and advanced manufacturing in the long-term.

Yet, these priorities risk shifting based on electoral cycles, lobby-driven policymaking, and agency leadership. The US government's efforts to guide strategic investments in various industries have thus produced inconsistent results.

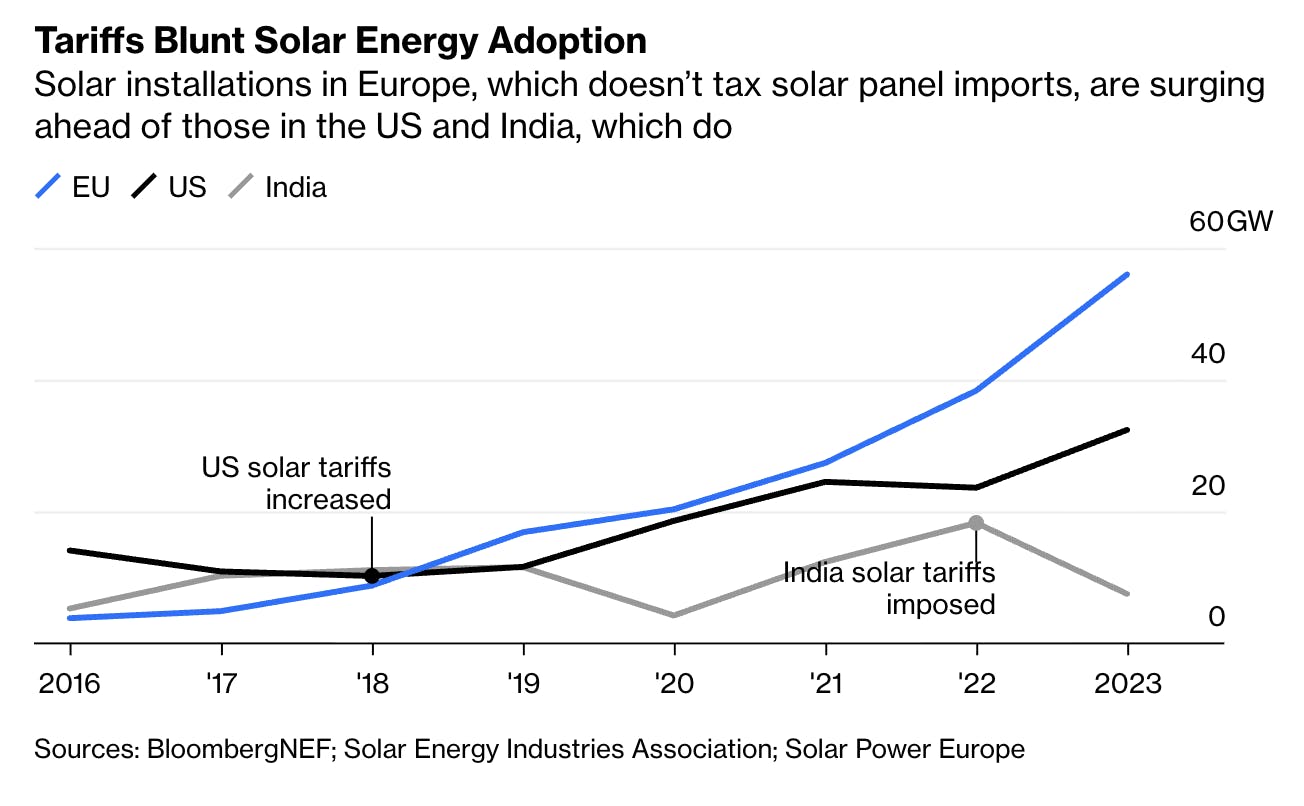

For example, the US lost leadership in solar manufacturing as its global market share collapsed by about 80% between 2011 and 2021, while China had scaled aggressively. This decline reflected structural weaknesses in US industrial policy. Despite strong growth in demand, with annual solar installation increasing by an average of 44% since 2005. Tariffs on imported solar panels, imposed in 2018 to protect domestic producers, were later softened and adjusted multiple times amid political and industry pressure, creating uncertainty that disadvantaged U.S. manufacturers competing with China’s heavily subsidized producers.

Source: Bloomberg

At the same time, lobbying by powerful incumbent sectors like agriculture and fossil fuels, which receive over $20 billion in subsidies annually, diverted political attention and resources away from emerging solar technologies.

The US’s maritime capacity followed a similar trajectory of decline. As of 2025, only 0.13% of the world’s large vessels are built in the United States, compared with roughly 60% in China. Nearly 80% of US trade by weight depends on ocean shipping, yet most of this commerce relies on foreign-built, foreign-owned vessels. By 2024, nine major European and Asian carriers controlled about 90% of America’s containerized shipping trade. Historically, Washington only bolstered shipbuilding during crises, funding massive wartime fleets and creating regulatory oversight through the Shipping Board. When this oversight was dismantled in the 1980s under Reagan and Clinton, long-term domestic capacity eroded. This pattern illustrates how fragmented, crisis-driven industrial policy leaves critical sectors vulnerable.

Semiconductor fabrication capacity has also eroded, with Taiwan now producing more than 90% of the world’s most advanced computer chips, forcing Washington to spend billions to reshore production only after dependence became a vulnerability. This loss of domestic capacity stems from a decades-long assumption from the US government that it could maintain global leadership by focusing on chip design while outsourcing manufacturing to lower-cost overseas foundries, a strategy that steadily hollowed out the country’s own fabrication base.

By intervening primarily in times of crisis and leaving long-term development to the market, the United States has thus repeatedly missed opportunities to build and maintain domestic capacity in strategically important industries.

How China Identifies Strategic Industries

The United States is now confronted with the geopolitical threat posed by China, a peer competitor that has combined long-term strategic planning with industrial policy to emerge as a major force in technology. China’s model is centralized, long-term, and rooted in clear state mandates.

National plans such as Made in China 2025 and the ongoing 14th Five-Year Plan designate several sectors as critical to national power, including information technology, robotics, green energy, new materials, and biotechnology. The China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund (“Big Fund”) raised $50+ billion for semiconductor development alone.

These designations are driven by high-level planning and agencies like the National Development and Reform Commission, not elections or short-lived political cycles. Through civil-military integration, China channels commercial technologies directly into defense and public infrastructure. Companies like SMIC and Huawei benefit from coordinated state backing, enabling them to expand despite export controls and sanctions.

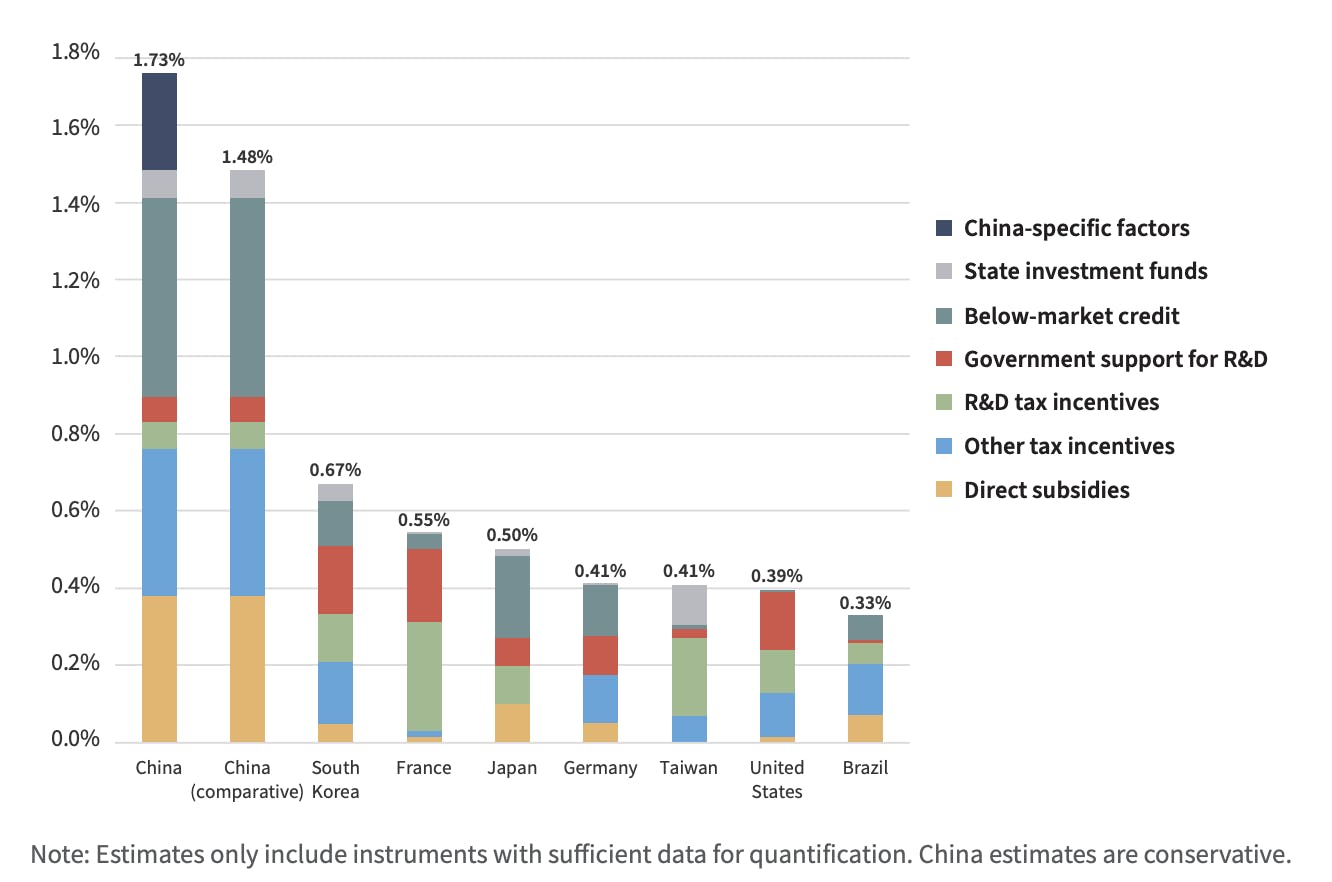

However, China spends an enormous amount on public subsidies, tax breaks, and below-market credit. In 2019, China dedicated the equivalent of 1.73% of its GDP to such support, compared to 0.39% in the US, and when procurement is included, the total could reach 4.9% of GDP, more than 12 times the US figure.

Source: CSIS

China’s approach also risks inefficiency and debt buildup due to indiscriminate subsidy flows. Although "Made in China 2025" listed 10 target industries, state funds have poured across dozens, fostering overcapacity (e.g., solar panels, electric vehicles) and mounting local government debt. Analysts have warned that while aggressive state coordination can accelerate technological catch-up, it often leads to waste, protectionism, and instability, as market signals are subordinated to political imperatives.

The Tradeoffs of Embracing State Capitalism

The contrast between these two models is quite stark. China shows how sustained, coordinated state support can accelerate technological catch-up, but also how indiscriminate subsidies create inefficiency and fragility. The Intel stake signals that the US, long reliant on fragmented and reactive measures, may be inching towards its own version of state capitalism.

On the positive side, government equity stakes can secure capacity in strategically vital sectors. By holding shares, Washington gains leverage beyond subsidies through acquiring a seat at the table in corporate decision-making. In semiconductors, where a single fabrication plant costs $20 billion or more, state ownership reduces the risk of firms offshoring production or privileging short-term shareholder value over long-term national security. Ownership also aligns public and private interests, as taxpayers share directly in the upside if companies succeed.

The drawbacks, however, are also significant. Equity stakes expose the government to financial risk if firms underperform. Past examples, such as the 2009 auto bailouts, cost taxpayers billions even though they ultimately stabilized the industry. Direct ownership also risks politicizing corporate strategy, with firms lobbying for favorable treatment or political leaders shaping industrial decisions for electoral reasons. Critics argue that this could slow innovation by making US tech companies more bureaucratic and less responsive to market signals.

Looking forward, the Intel deal sets a precedent. If semiconductors are deemed too strategic to leave fully to the market, similar arguments could be made for defense-adjacent firms like Palantir, or even foundation model developers such as OpenAI. The central question is whether partial nationalization represents a pragmatic adjustment to global competition, particularly China’s state-backed model, or whether it risks undermining the very market dynamism that has historically made the US an innovation leader.