Over the last two decades, software has gone through a rapid evolution. In the early 2010s, Marc Andreessen said “software is eating the world.” Just a few years later, in 2017, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang said that, while software is eating the world, “AI is going to eat software.” Now, we see Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella saying that the software era might be over:

“[SaaS] applications [will] collapse in the [AI] agent era. [They’re just] CRUD databases with a bunch of business logic.”

From the up-and-coming disruptor to the dominant world-order to, very quickly, being on the chopping block of disruption. Predictions of the death of software are around every corner. But the reality is that the rumors of the death of software in the age of AI have been greatly exaggerated.

The Software Trade-Off: Customizability vs. Cost

If you go back through the history of software, you see that each pivotal moment was effectively a trade-off between customizability and cost. And reducing cost has almost always won out as the highest priority.

Source: Contrary Research

Starting with the very first mainframes in the 1940s to the 1960s, like the ENIAC and UNIVAC, you have massive complex machines that take up full rooms and are individually hand-wired or hand-coded. With every build being a custom job. You had maximal customization (within the technical capabilities of the time), but it came at an extremely high cost.

Then you enter the personal computer era, but what you get is an experience that is actually far from personalized. In order to make software mass-distributable, you couldn’t make it adaptive. You could have different machines or programs for different purposes, but each served a specific function.

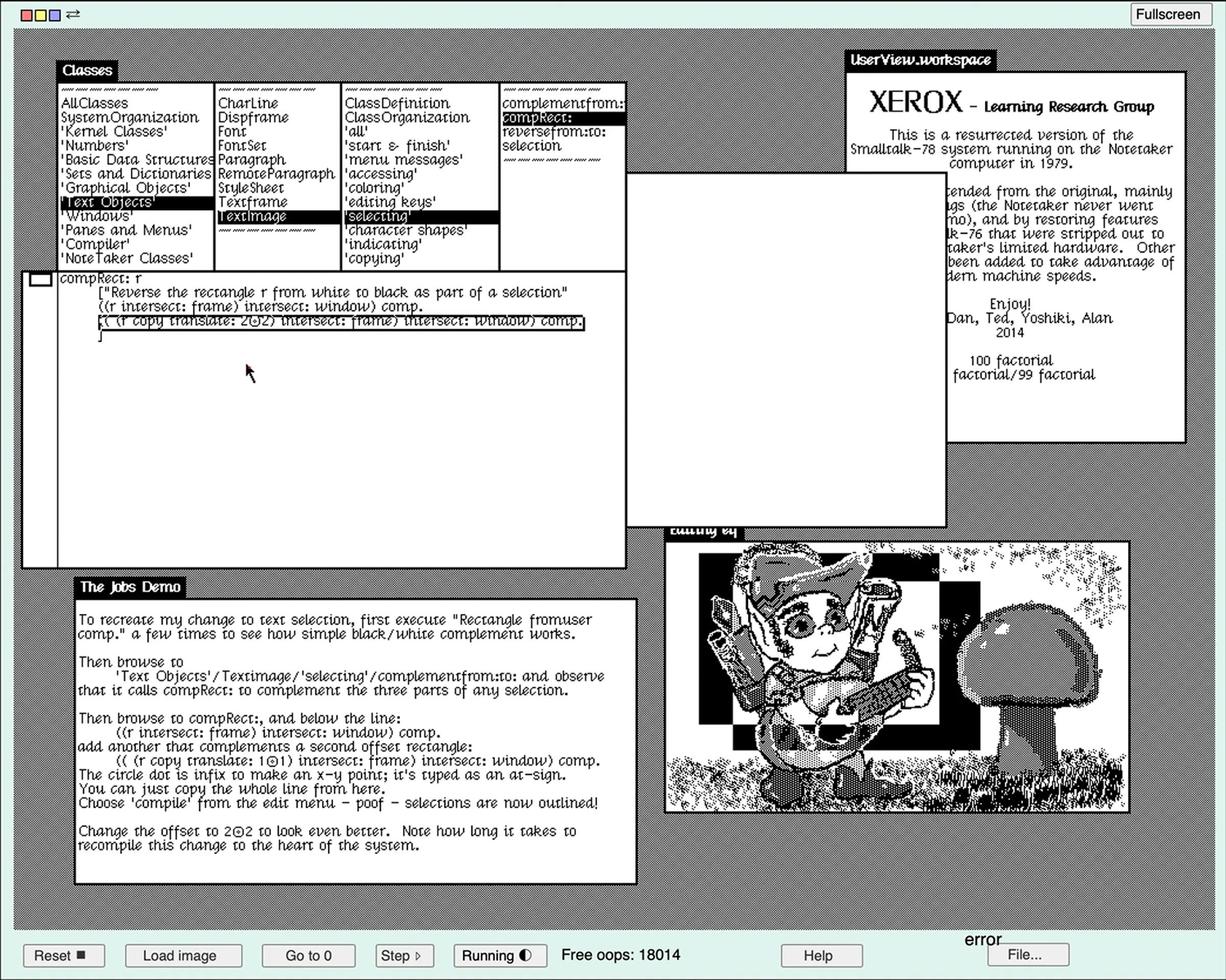

In fact, as we see in this scene from history recreated in the movie “Pirates of Silicon Valley”, personal computing was actually defined by a road not taken. A lot of people know the story of Steve Jobs’ inspirational tour of Xerox PARC and his introduction to the graphical user interface (GUI). But that was just a teaser of what he could have taken from that tour.

Source: Mac History

Smalltalk, the programming language that enabled the GUI, didn’t actually stop at making the interface adjustable. It was a programming language that enabled an entire interactive computing environment. Everything on the screen was a live object that could be modified and personalized. But Apple’s takeaway, again in the pursuit of reducing the cost of computing, was in favor of a fixed GUI. What felt like a unique experience for anyone who hadn’t experienced a GUI before, but one that would ultimately be the same for everyone.

Source: IEEE Spectrum

Once again, the industry made the choice to sacrifice customizability to enable increasingly lower costs.

Then you have the twin revolutions of software distribution: cloud computing and software-as-a-service. It’s important to emphasize that you can’t understate how important these things were for software distribution; it was a breakthrough. Between cloud providers like AWS and new-age SaaS solutions like Salesforce, software had never been easier to distribute. But as a result, while software became easier to access, it also became harder to tailor. Costs plummeted, but customizability got pushed to the fringes.

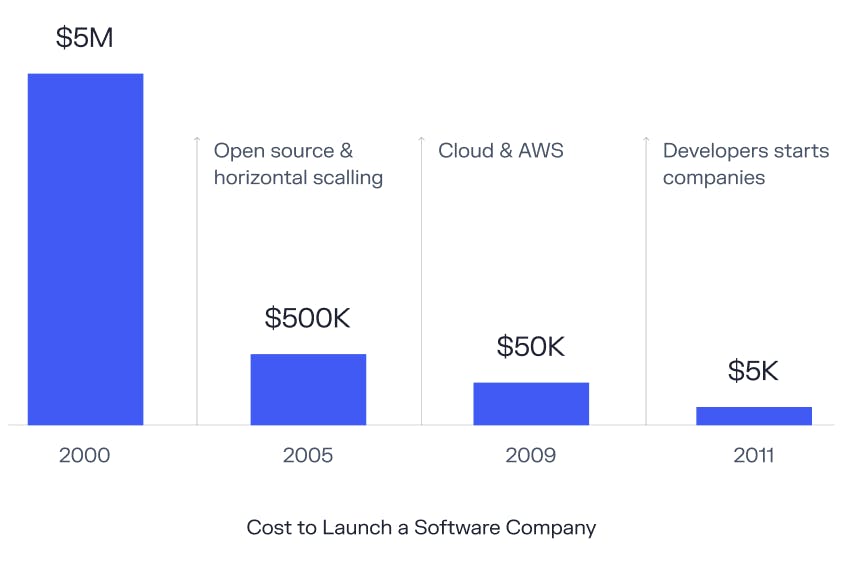

Source: Mark Suster; Contrary Research

As a result of this manic pursuit of cost reduction, we saw the cost of building a software company plummet. Today, the promise of AI could further reduce the cost of software production to near zero. But the question is whether that’s all AI will do. Will software maintain its march towards simply being as cheap as possible? Despite the technological breakthrough of generative code, the current paradigm of SaaS may still keep us locked in a uniform way of building because of the philosophical foundations of how software is built.

Monolithic SaaS & Extensibility

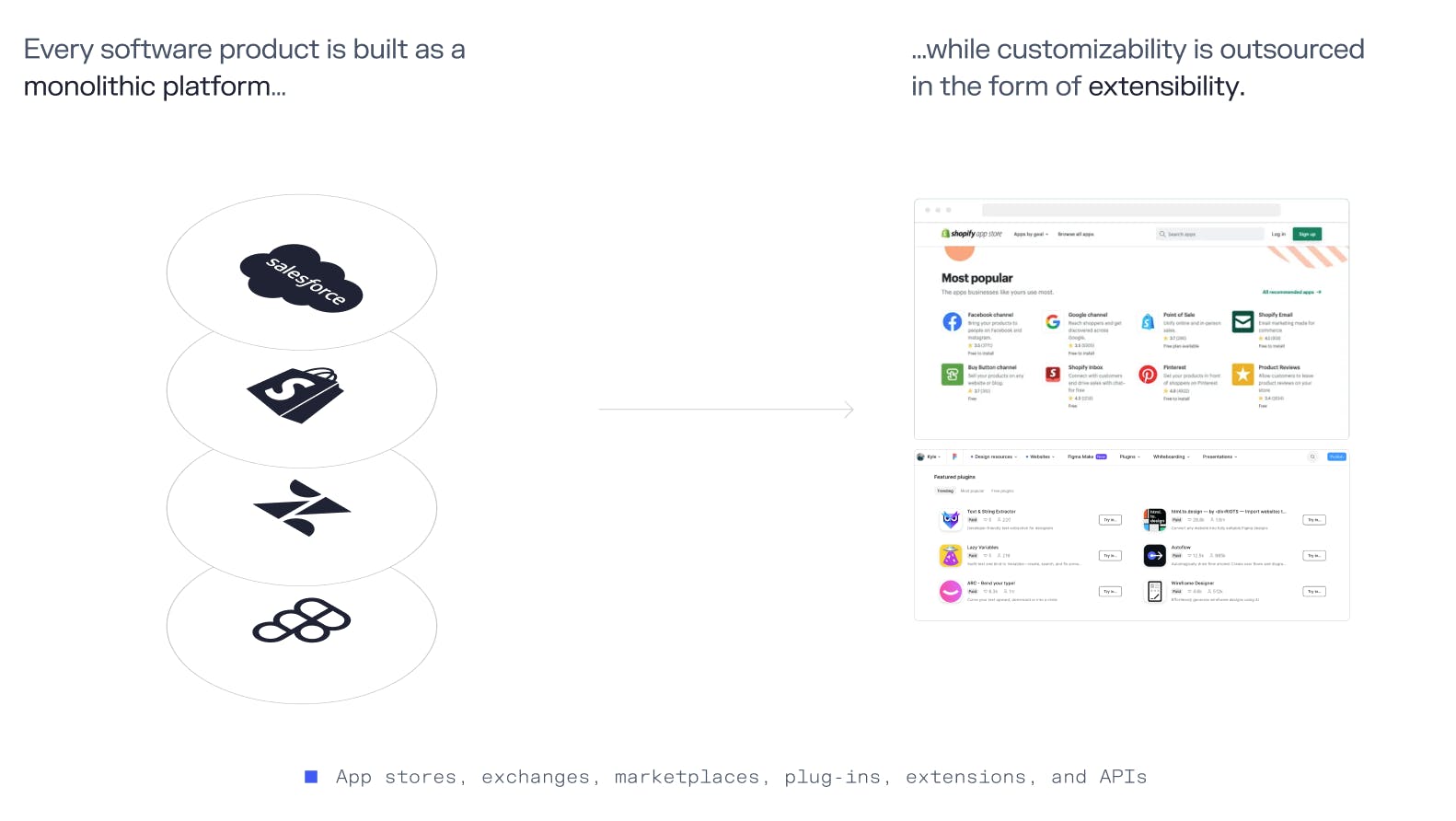

Source: Contrary Research

In the pursuit of cost reduction and SaaS distribution, the psychology around how we build software in the Golden Age of SaaS crystallized around this idea that you only ship one product. One code base to rule them all.

Basically, every major software platform since the advent of SaaS has been built as a monolithic code base. In some cases, the closest you come to software customizability within that monolith is whether you can have light mode or dark mode.

Any expansion of features or capabilities, rather than being enabled within the product, goes into one of two buckets: (1) either into the master backlog of feature requests vying for entry into the monolith, or (2) packaged externally as a plug-in or add-on.

The quality of software was defined by the quality of the product in the monolith. Customizability of the software came in how extensible it was. How open access is the product? Is it API-friendly with a thriving third-party app ecosystem? Or is it a walled garden where what you see in the code base is all that you get?

In fact, many of the most recognizable software tools of the latter half of the Golden Age of SaaS are extensibility enablers: Stripe, Twilio, Plaid. API-centric businesses that protect the sanctity of your code base from an onslaught of adjacent capabilities in payments, messaging, or bank access.

Modular Software

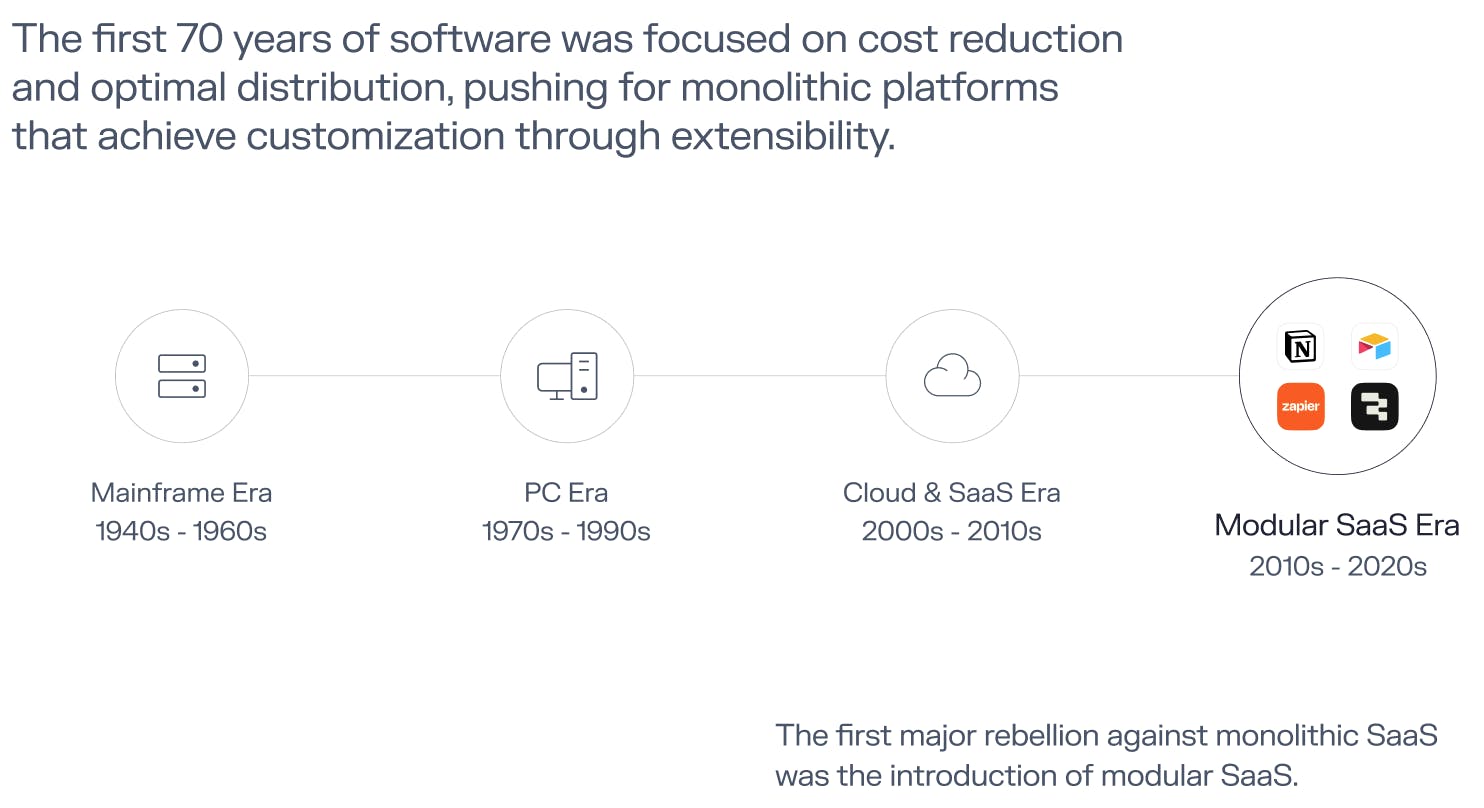

Source: Contrary Research

After 70 years of software cost reductions, we started to see the first pushback to the march of monolithic SaaS in the introduction of modular software. Companies that were founded in the first half of the 2010s, like Notion (2013), Airtable (2012), Zapier (2011), and Retool (2017).

Each has articulated the belief that software was meant to be more flexible. Ivan Zhao, the CEO and co-founder of Notion, has even described the original vision for Notion as enabling people to “make and create their own software.” He references the original vision of Smalltalk from Xerox PARC as an inspiration for that.

But while modular software was attempting to break down the monolith, it was still limited. The best these tools have been able to do is offer some internal building blocks that could be more mixed and matched than your typical monolith.

If extensible monolithic software stayed fixed internally and reached out to external ecosystems for customizability, then modular software enables some customization within its internal building blocks, but it still stays fixed within a set paradigm of how those building blocks can be used. For custom capabilities, these tools are even more accessible to external ecosystems. But that inability to evolve doesn’t mean software is dead. Far from it. It’s evolving. And the opportunity is bigger than just some blocks we can move around on top of a consistently fixed foundation. The goal is composable software.

Composable Software

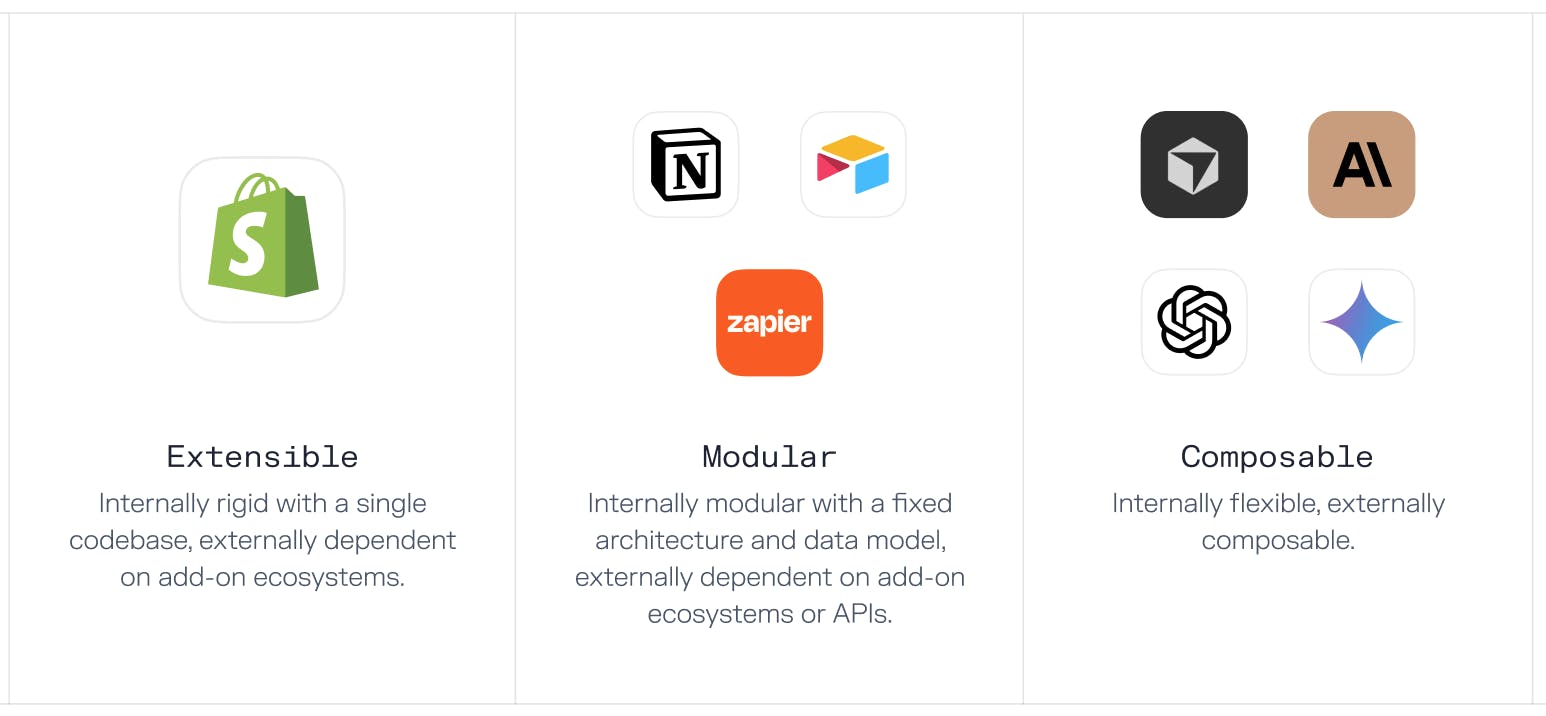

Source: Contrary Research

Software that is fully composable is more than just flexible. It can be reconfigured, either manually or even autonomously. Before AI, the friction was too high. Modular platforms like Airtable and Notion had to maintain some semblance of opinionated paradigms because there would be too much work inherent in making their internal systems infinitely adjustable. But AI makes that composability accessible without dramatically increasing the complexity of using the software.

The defining characteristics of composable software are systems that are built up around independent and interoperable capabilities that can be dynamically assembled into new systems. Where extensible software relied on bolt-ons and modular software just offered predefined components, composable software actually focuses on primitives as building blocks rather than concrete products.

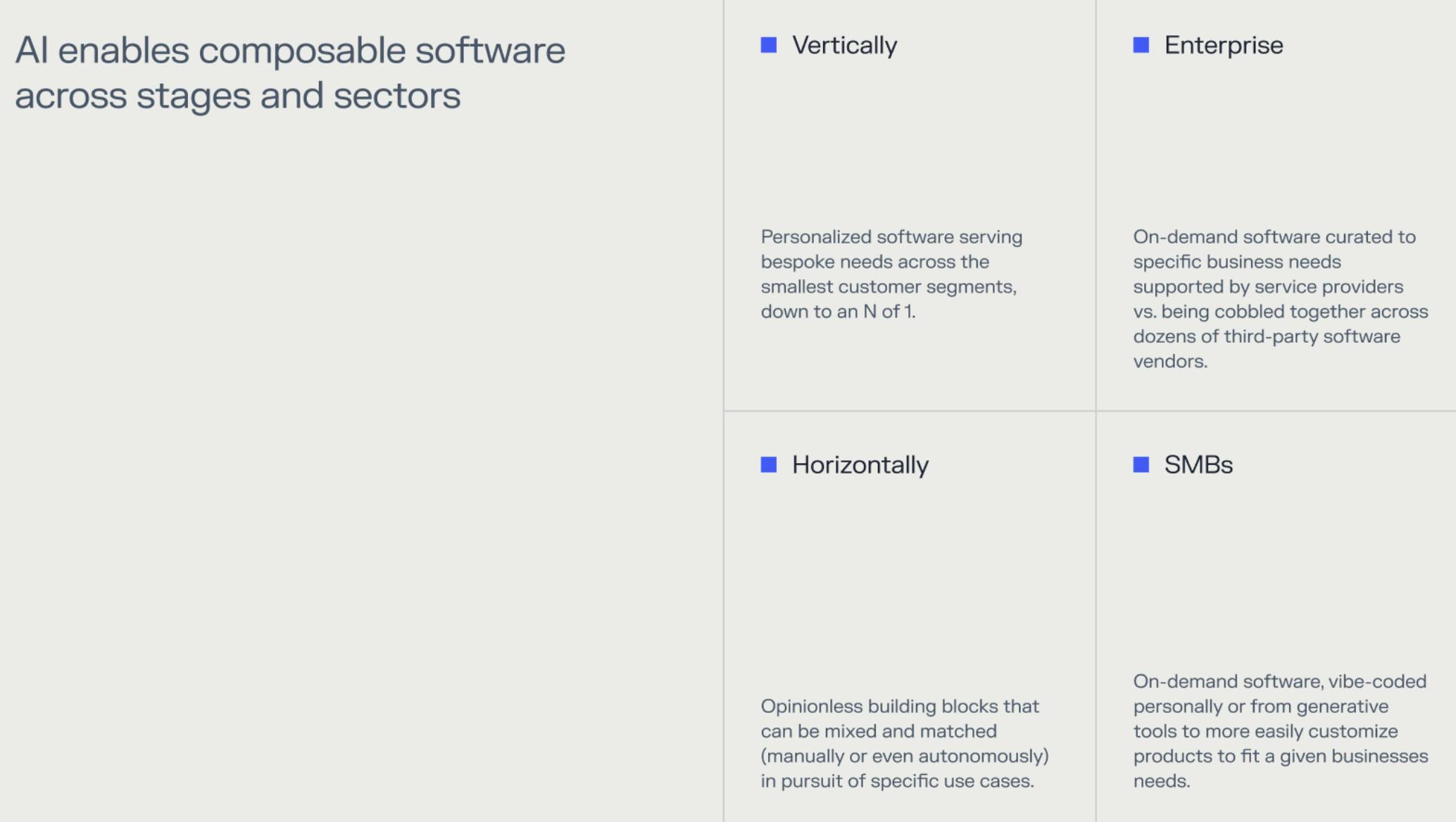

The vision for fully composable software has implications for both vertical and horizontal SaaS, as well as across customer bases spanning from enterprise to SMBs.

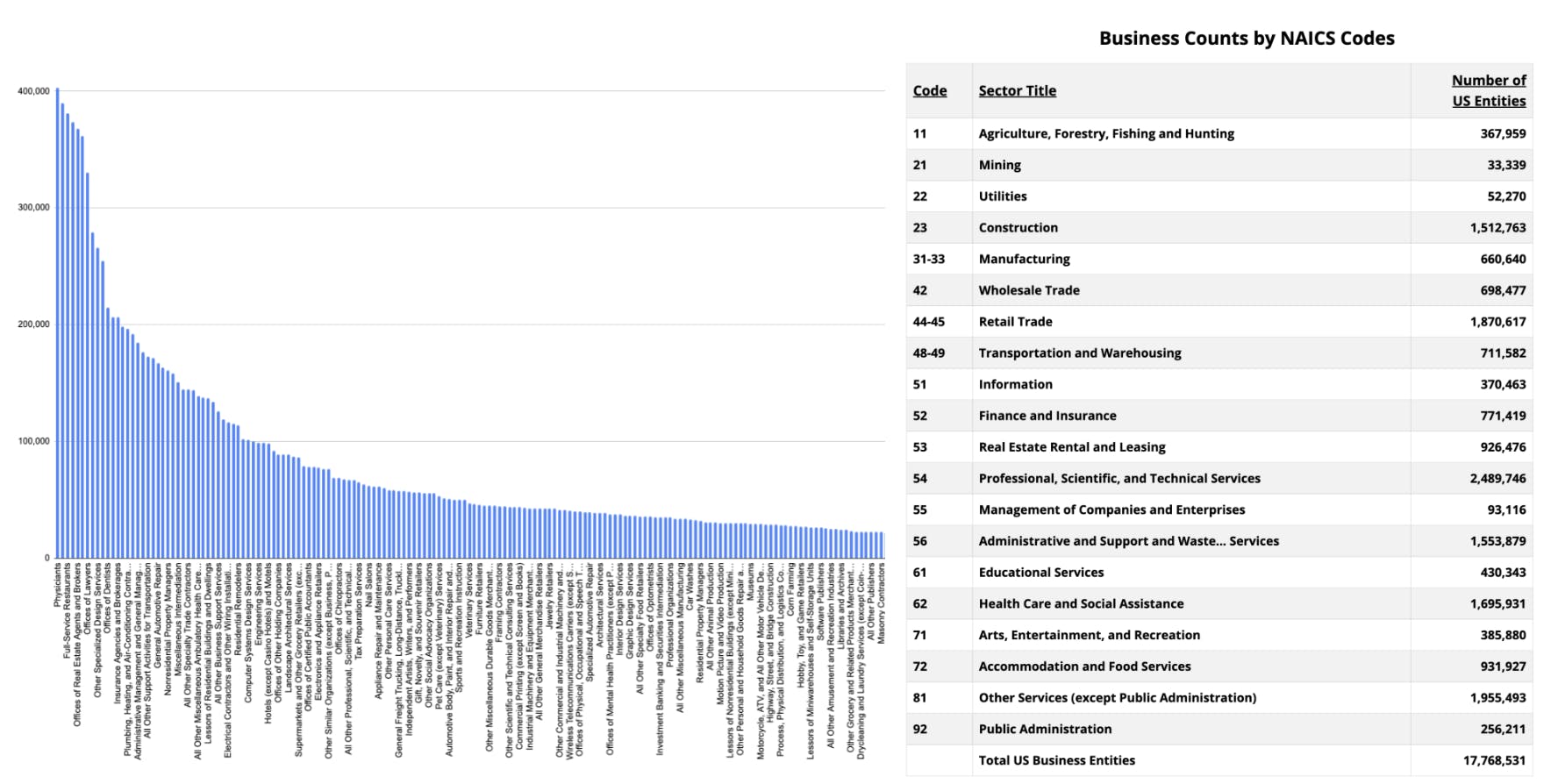

Starting with vertical SaaS. Anyone worth their salt who was invested in or built around vertical SaaS is intimately familiar with the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes. When you see the census data across 17M businesses in 1K different verticals, you realize that “vertical software” doesn’t exist as a category of products. It’s thousands of categories.

Source: NAICS

And most of those categories have typically been underserved by the monolithic software paradigms of the past.

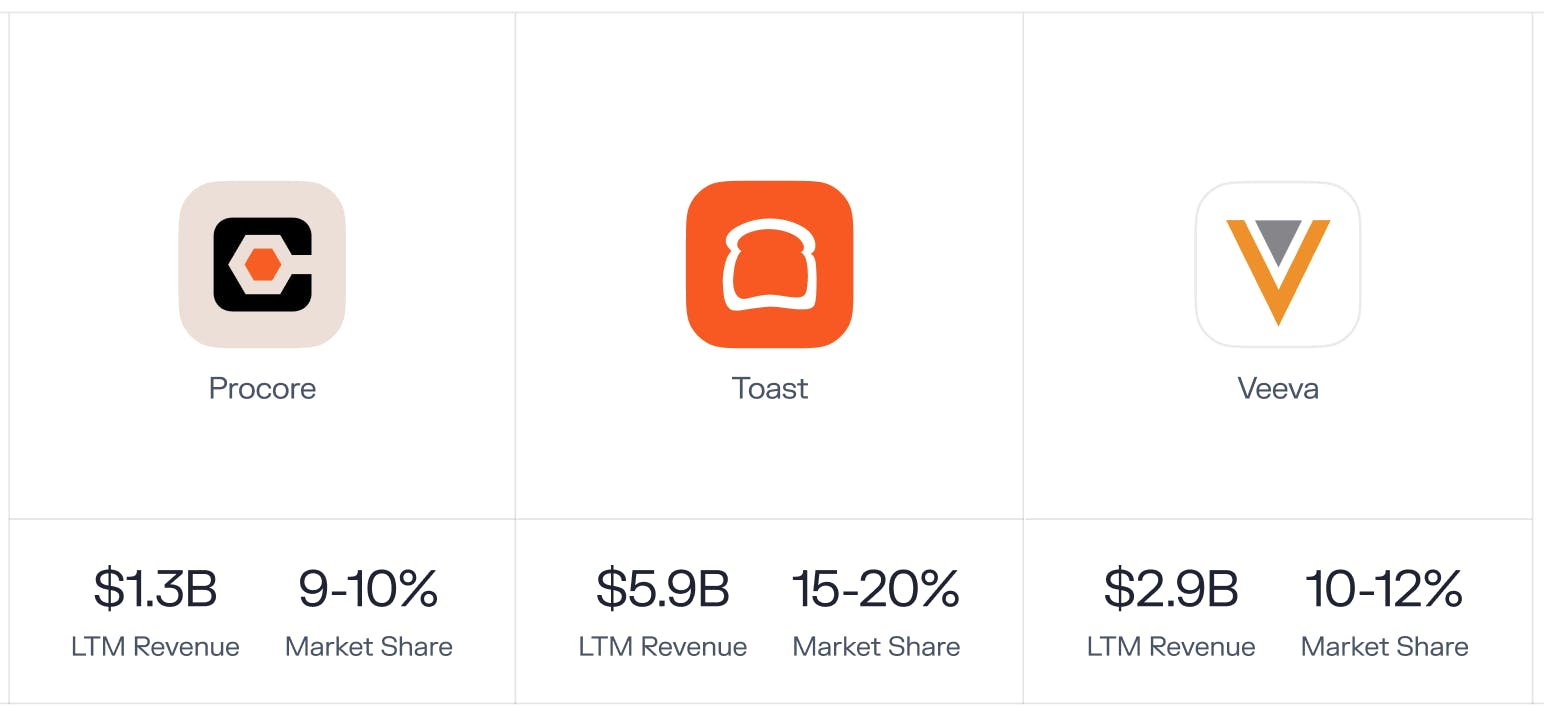

There are, most certainly, multi-billion-dollar success stories in vertical software. In most cases, it’s because these companies have found “riches in niches” by targeting specific subsets within their “verticals.” Procore with smaller general contractors, Toast with independent restaurants, and Veeva with the largest pharma companies.

Source: Contrary Research

The largest vertical SaaS company is probably Shopify, and it is a masterclass in extensibility. Firm foundation with an infinitely extensible universe for customizability. But the vast majority of customers in the long tail of any given vertical are still dramatically underserved by software.

Think about it this way. There are 700K restaurants in the US. There are 6 million home service professionals. 900K construction companies. No vertical SaaS company can build such a disparate population. Instead, they build for the least common denominator: the average participant in a given vertical. The logic has always been that you need to try to pick something to be good at because you can’t do everything for everyone.

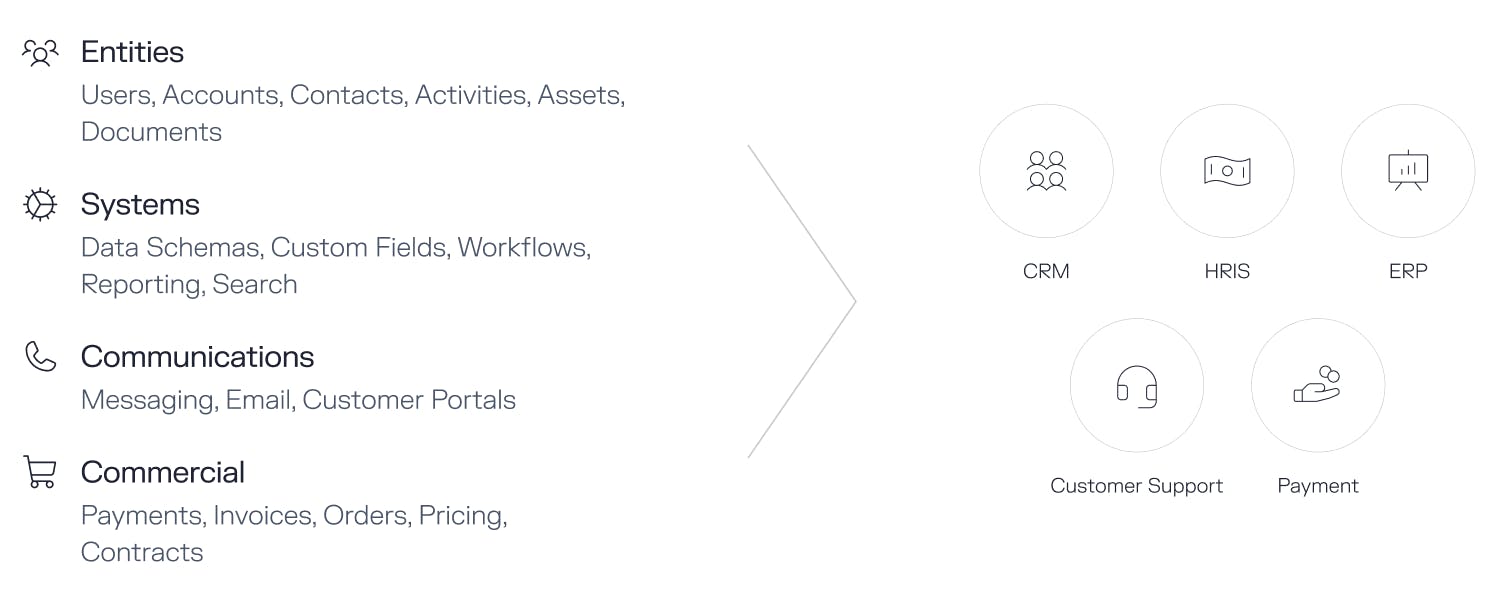

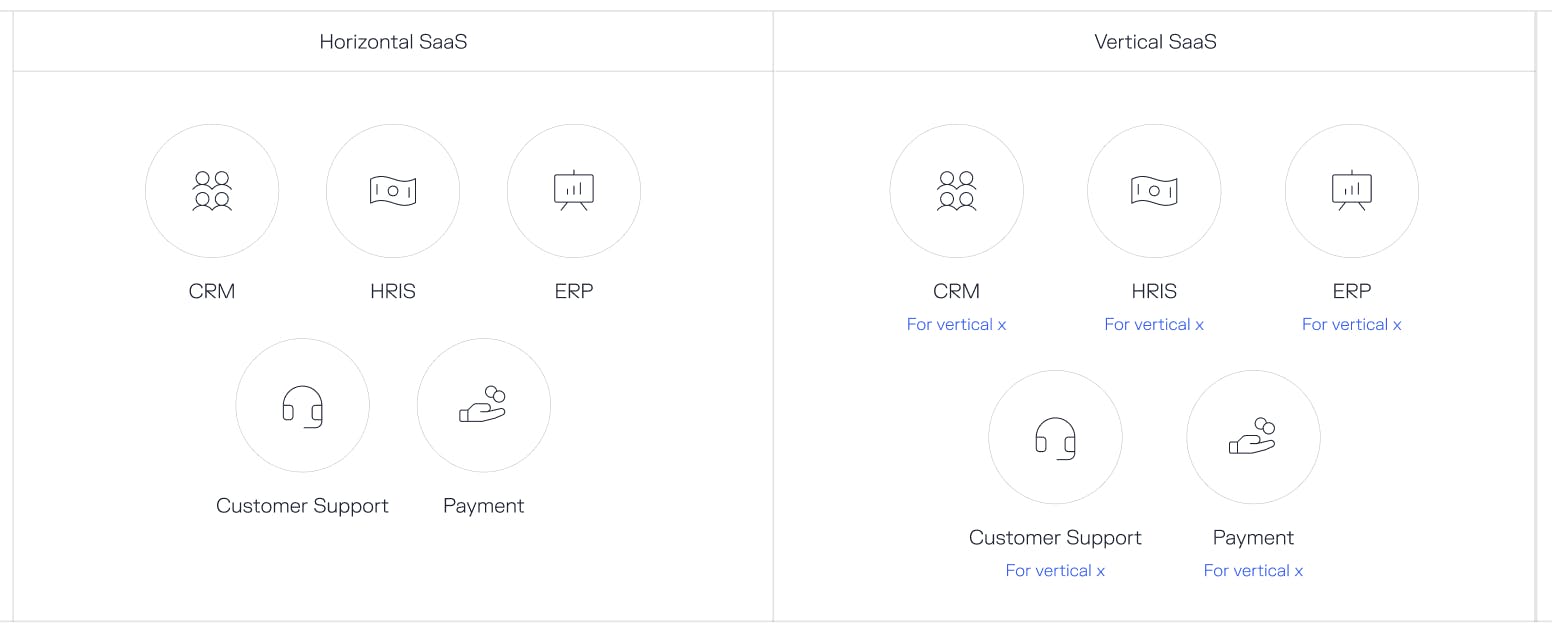

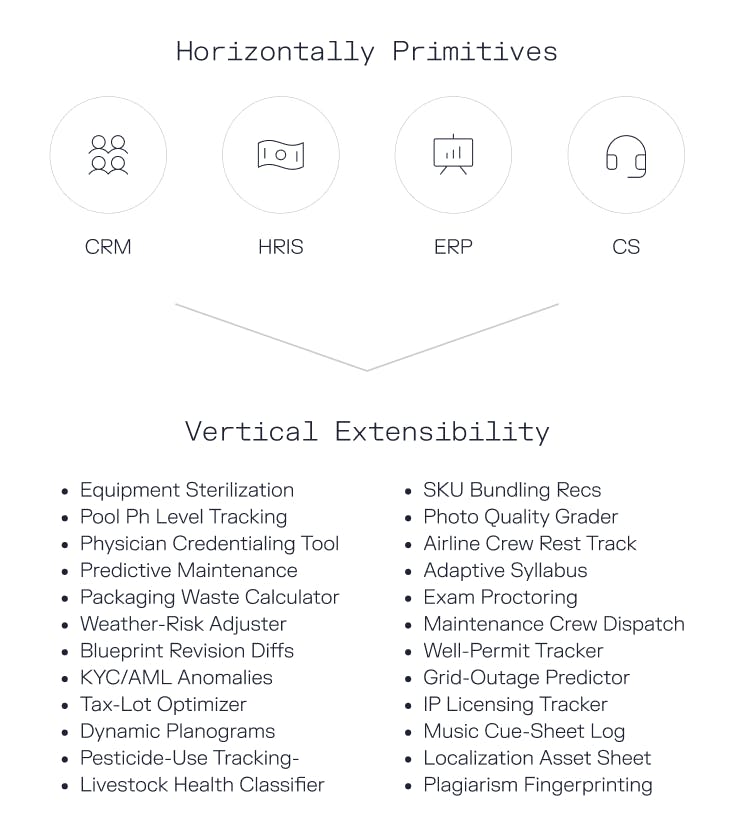

When you break down what vertical SaaS is, you start to realize that vertical SaaS is just a combination of horizontal software primitives bundled together in pursuit of a specific use case. From entities (users, accounts, contacts) to systems (data schemas, search fields), communication (messaging, customer portals), commercial functions (payments, invoices, orders), and on and on. Horizontal software is made up of those same primitives.

Source: Contrary Research

Vertical software is just horizontal software with vertical-specific business logic infused into the code base. But that makes it fundamentally inflexible. The friction of building vertical SaaS was finding enough common ground across different participants in a given vertical who are able to wrap their operations around your “customized” business logic.

Source: Contrary Research

But AI enables vertical SaaS to become infinitely personalizable because the friction of creation is so low. AI should also enable horizontal SaaS to become more composable, not only because it’s easier to build, but because eventually agents will be able to stitch those building blocks together autonomously.

As a result, you get a foundation of horizontal primitives that can be infinitely extensible into any vertical, no matter how small. You could think of this as diagonal software: a foundation of horizontal primitives that don’t have to be reinvented, but can be plug-and-play, while also infinitely extensible into niche vertical capabilities without high friction or technical weight on a monolithic codebase.

When we think about customer segments of very different sizes, everything from that N of 1 segment to an SMB or even up to an enterprise, today you see a wide spectrum of software usage.

SMBs don’t use enough software. Enterprises use too much of it! But the underlying reason behind both of those decisions is very similar. SMBs can’t find software that fits their needs, either because it doesn’t work for them or the friction of using it is too high. Enterprises try to find software that fits their needs. And you have people whose job can be puffed up by “managing systems,” so they push to adopt software. But the hit rate is just as low. 30-50% of the software being used by enterprises is wasted.

The idea of software on demand will exist on a similar spectrum. On the one end, you have SMBs who might vibe code a project manager uniquely curated to their needs. On the other end, you have enterprises wielding a combination of Accenture + AI tokens to try to custom-create their internal tools.

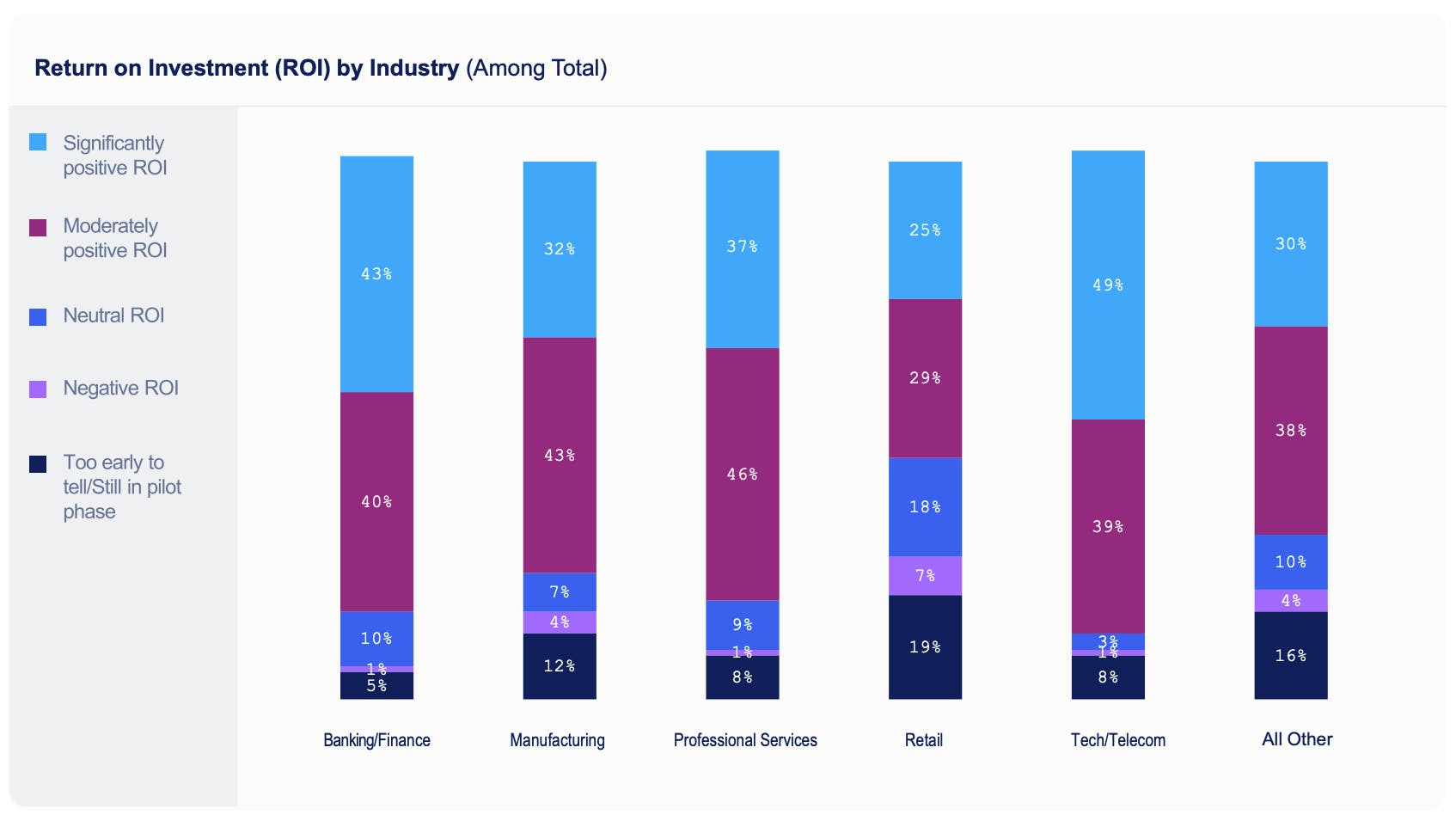

Skepticism abounds across countless examples as people misuse AI, like any technology before it. And there are plenty of limitations in people’s ability to use it correctly, as well as limitations in the underlying capabilities of the technology thus far. But the reality can’t be ignored. Across industries, companies are experiencing productivity gains and cost savings from using AI. Already, companies are enacting programs that could save tens of millions of dollars in costs by using AI to make processes more efficient or entirely cut out large swaths of third-party software spend.

Source: Wharton

Compass, the real estate tech company, said, in its Q2 2025 earnings call, that the company was already seeing massive cost savings from AI:

“We now have a new program already underway that will drive $50 million to $75 million of incremental adjusted EBITDA… through continued focus on cost efficiencies, [including] a reduction in costs driven by use of AI across various areas of our technology and operational functions.”

Similarly, Josh Wolfe, of Lux Capital, has said that he expects “a lot of tech forward companies will use AI to replicate internally the software they use from third-party vendors and cut the majority of their current SaaS deals.” So whether it's more formalized enterprise software on-demand with service providers helping pull things together in a secure and managed way, or a more informal SMB version that could consist of anything from individual vibe coding to simpler platforms built with AI-native principles of maximum composability. The evolution taking place in software is coming directly from the implications of composable software.

Source: Contrary Research

The Delivery Mechanisms of Composable Software

The final question is one of pragmatism. Composable software is a conceptual framework for how the production of software will evolve. But when the rubber hits the road, what kind of new software companies will we see getting built?

Vibe Coding

The first we’re already seeing. Simple “vibe coding” either to produce standalone apps, like Base44, or internal tools, like the document finder vibe coded by Pinterest employees that now handles 4K questions per month. The biggest question for these tools will be effective maintenance. And I think we’ve only scratched the surface of that iceberg.

Vertical SaaS + Domain-Specific Models

Source: Nice, Samsara, ServiceTitan, Duetto; Contrary Research

Another version of this we’re already seeing is established platforms dipping their toes in the water. Vertical SaaS companies have existing install bases that give them an immediate platform for their AI products. Going forward, the opportunity will be to weave things like domain-specific models into their workflows to make their AI products even more effective.

Horizontal Primitives + Vertical Extensibility

Source: Contrary Research

But the real paradigm shift from composable software will come as it becomes easier for new companies to build primitives as their primary product. From there, you could start to see the reemergence of extensibility in the form of vertical applications.

In a world where a traditional vertical software company wouldn’t have built the fringiest feature requests, now those pieces can be built more autonomously by either the owner of the horizontal primitive, third-party service providers, or freelance app developers. You could imagine a world where Bob’s Pool Emporium could pull a horizontal software primitive off the shelf, vibe code its own unique vertical extensions, and white-label it to its customers.

Those combinations can also increasingly be composed not just manually, but autonomously by agents trying to complete specific tasks.

Self-Driving SaaS

The eventual outcome of composable software is what Karri, the CEO and founder of Linear, has described as “self-driving software.”

Source: Linear; Contrary Research

Karri describes the first instinct AI gave everyone as “the chatbot era.” But we’re still nudging software along, just with prompts instead of button presses. Self-driving SaaS is the potential for future systems when “AI stops requiring constant user input” and starts to “proactively move work forward.”

Linear’s version of self-driving SaaS is a system that automatically takes in requests from sales calls and support tickets, triages them into the necessary operational orgs, and then either dispatches a coding agent for simple fixes or adds contextualized assignments to relevant teams.

Source: Linear; Contrary Research

Software: An Asked and Answered System

These are just some of the opportunities as the cost of producing software approaches near zero and composable software unlocks all the prior limitations of monolithic SaaS products. In the same way that SaaS, and the internet, and mobile, and AI have defined how technology companies were built in prior evolutions, composable software will unlock a similar pool of opportunities.

Software will become self-driving by leveraging composable building blocks. Horizontal primitives with vertical extensibility. Software will shift from revolving around monolithic products to being either manually or autonomously composed of primitives. The era of cheap software allowed software to eat everything. Now, the era of personalized software will allow software to enable everything.

Steve Jobs once made a prediction about technology’s ability to provide the perfect tutor from the halls of history:

“We are now entering a revolution of free intellectual energy… My hope is, someday, when the next Aristotle is alive we can capture the underlying worldview of that Aristotle in a computer. And someday some student will be able to not only read the words Aristotle wrote, but ask Aristotle a question. And get an answer.”

This quote is cited frequently, often in the context of AI tutors. But is also a fundamental framing for all software. Software is, fundamentally, an asked-and-answered system. Every piece of software revolves around a “job-to-be-done” type of question.

When we reflect on the role that software will play in our lives going forward, it will revolve around every function of value. Every job-to-be-done. We have problems that need solutions. In the past, software offered solutions, but in line with the least common denominator. The average user experience. Going forward, we can answer those questions with increasingly composable software that can be personalized to meet the needs of very specific use cases and individual users.