Actionable Summary

The uneven adoption of AI has created a paradox. Despite billions invested and rapid advances in generative models, 42% of enterprise AI initiatives were discontinued in 2024. The reason isn’t the models themselves, but how they’re embedded into businesses. The winners won’t simply build copilots; they’ll redesign workflows, rethink structures, and in some cases, take ownership of the service layer where value is created.

History offers a roadmap. Serial acquirers like Waste Management, United Rentals, and Constellation Software showed that disciplined capital allocation and repeatable M&A can compound for decades. Their success stemmed from choosing the right structures with a focus on deciding where every dollar and every hour earn the highest return.

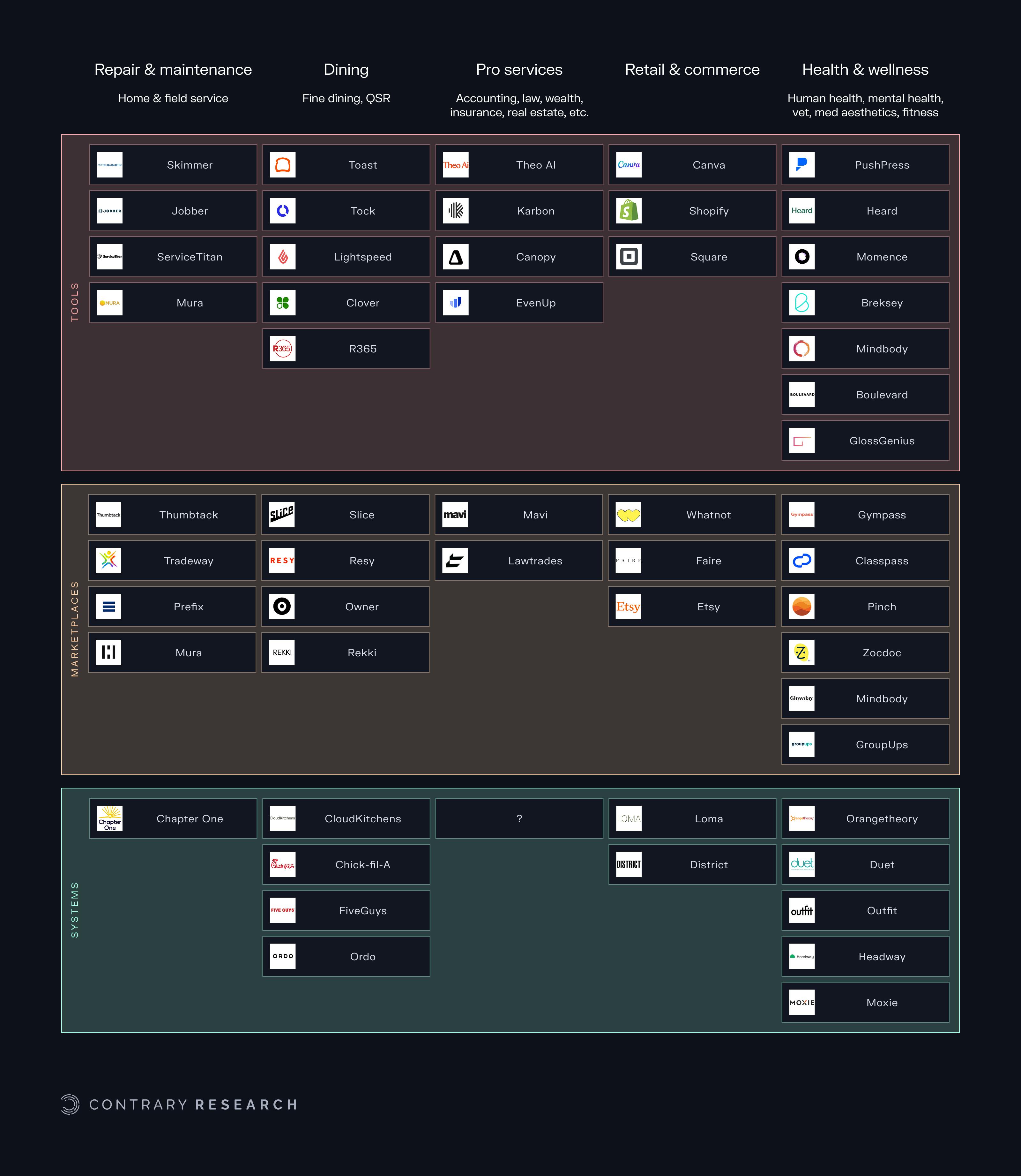

Vertical SaaS once won by digitizing industry-specific workflows, from restaurant payments to plumbing dispatch. With generative AI, the scope expands beyond record-keeping into execution, allowing founders not just to organize work but to perform it. This shift enlarges the addressable market for vertical software, since AI can capture portions of labor spend alongside software budgets.

Just as past consolidators had to decide whether to centralize or decentralize operations, today’s AI founders face a structural choice: is it more effective to sell tools to incumbents, or to own the operating layer where those tools are applied? Each path carries different implications for capital intensity, distribution, and defensibility.

For founders who are building in vertical AI, the work begins with mapping workflows, running targeted pilots, and testing whether distribution can scale efficiently. It also requires aligning capital and talent with the model being pursued. These steps reduce the risk of failure and keep design anchored to market reality. The goal isn’t to prescribe a single path for distributing vertical AI, but to give leaders a process they can revisit as customer behavior and market conditions evolve.

The next generation of CEOs will look less like pure technologists and more like capital allocators. Their job is to treat AI not as a feature but as a labor class, and to deploy it with the same discipline that the most successful serial acquirers applied to capital. The challenge is deciding where to play and how to structure ownership. The opportunity is to turn AI from pilot projects into compounding engines of cash flow.

The Terrain

“The future is already here – it’s just not very evenly distributed.“

— William Gibson

In May 2025, shortly after the release of Sonnet 4, Anthropic’s CEO Dario Amodei delivered a warning to the US government and population: “AI could wipe out half of all entry-level white-collar jobs — and spike unemployment to 10-20% in the next one to five years”. Yet at the same time, according to S&P Market Intelligence, 42% of enterprise AI initiatives were discontinued in 2024, up from 17% in 2023. What explains this gap between the promise of AI and its adoption?

LLMs are shaping up to automate significant portions of knowledge work. That change could create margin uplift opportunities for non-technology businesses. But meaningful AI adoption remains uneven across industries. While advanced AI tools and platforms have become increasingly available, genuine operational change remains elusive for many as they pursue AI to improve customer experience, efficiency, and profitability.

This is leading to a shift in how software companies are built, and even what kinds of companies get built in the first place. Instead of selling software to traditional businesses, some founders and investors are increasingly choosing to own or operate the businesses themselves and leverage AI from within; what many are calling an AI rollup. In this model, founders take over direct control of the service and can dictate how a product is used, whether because they acquired existing companies and are weaving AI in retroactively, or by building new AI-native service companies from scratch.

Direct ownership or operation of a traditional company, versus selling to one, removes the need for sales cycles, change management, or customer education. And if you believe AI can meaningfully increase the margins in a given industry, then the fastest way to capture that upside may be to run the business yourself. As founders look to build technology companies, there are three distinct but complementary pathways emerging:

Selling software: Building AI tools that help existing businesses work more efficiently

Buying and modernizing operators: Acquiring existing businesses and embedding AI

Building from scratch: Starting new, fully integrated businesses designed around AI

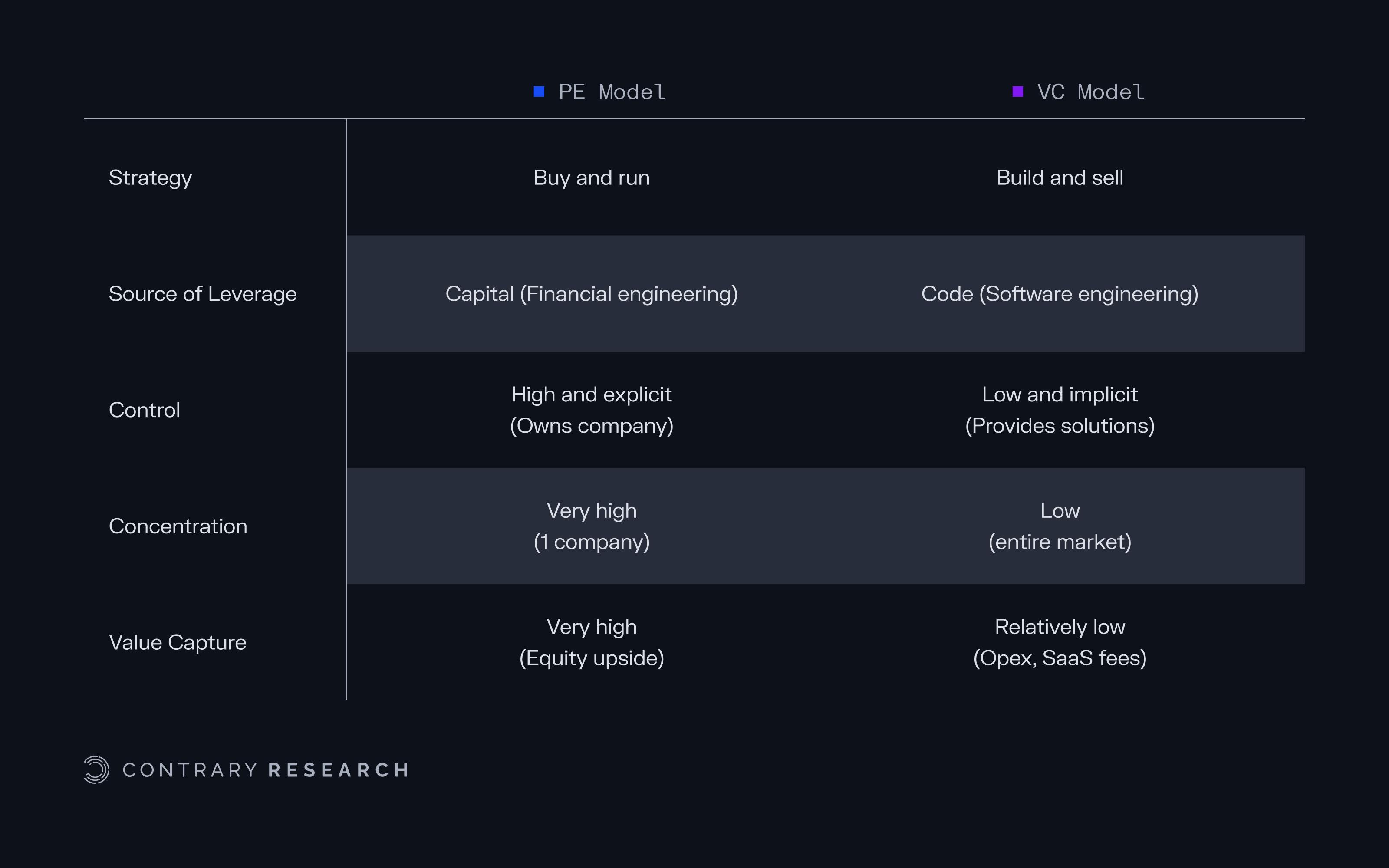

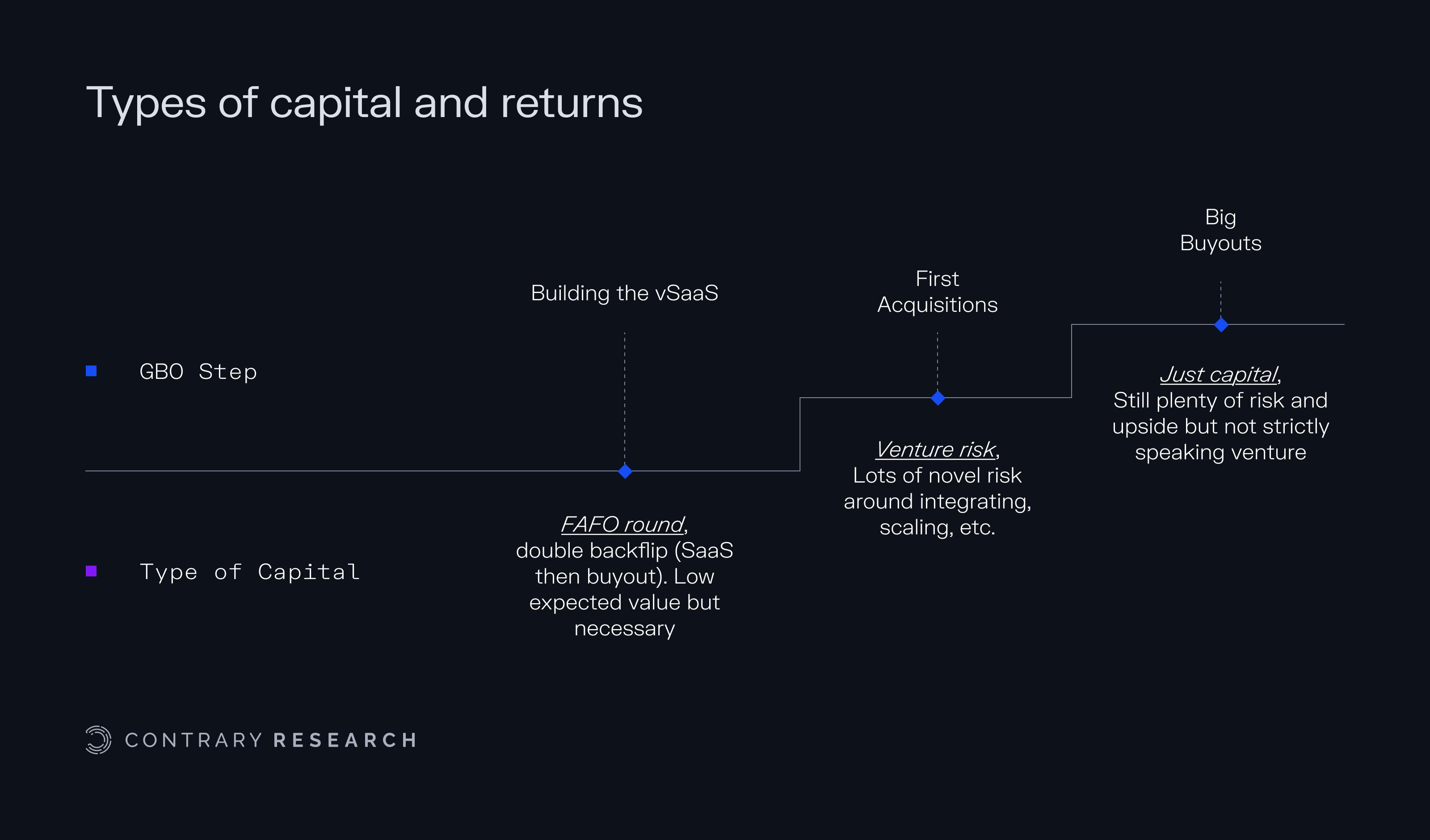

Ultimately, each path requires capital; the question is who supplies it, and why? Historically, private equity and venture capital operated with distinct mandates. Private equity focused on acquiring mature, cash-generating businesses with an eye toward operational improvement and debt leverage. Venture capital, by contrast, invested in startups with higher risk and higher growth potential, accepting lower near-term efficiency in exchange for outsized long-term outcomes. However, the distinction between venture capital and private equity has always been more of a spectrum than a wall. As one investor notes:

“Both models start with the same principles: (1) the average company in a given vertical isn’t run as effectively as it could be, and (2) you have the insights and playbooks to run the average company more effectively.”

Source: Matt Brown; Contrary Research

What separates private equity and venture capital funds is not intent, but how much control they seek, how concentrated their bets are, and how they plan to extract value. In recent years, however, these boundaries have begun to blur. For much of the last two decades, venture capital succeeded by staying predominantly asset-light. Most investors preferred startups that scaled through software rather than operational complexity. But as traditional tech categories become saturated and AI unlocks efficiencies in older industries, a new strategy is emerging, and some investors are reorganizing around that reality. Several venture firms are beginning to support acquisition-driven platforms that combine technology with real-world operations.

As an example, Slow Ventures has formalized what it calls the “Growth Buyout” strategy. Will Quist, a partner at Slow, argues that in many legacy sectors the upside from selling software is “not worth the squeeze”. Sales cycles are long, pricing power belongs to entrenched oligopolies, and customers are lenient about paying. Slow’s answer is to buy a legacy operator outright, arm it with proprietary software, and let the improved cash flow finance the next acquisition.

In another example, Thrive Capital created Thrive Holdings, a dedicated $1 billion roll-up vehicle to invest in everyday industries, in 2024. Its model is to help operate these businesses directly and use their cash flow to fund further acquisitions. Thrive has already backed Crete, an accounting platform, and Long Lake, a consolidator of homeowner association managers.

General Catalyst (GC) announced its incubation of HATCo (Health Assurance Transformation Company) in October 2023, which acquired Ohio-based healthcare system Summa Health in January 2024. HATCo is a part of GC’s wider Creation Strategy, towards which the firm has raised $1.5 billion. The strategy is designed to partner with founders to build new companies from scratch, often in combination with an “AI-enabled roll-up model”.

Other investors, including 8VC, Khosla Ventures, a16z, and Elad Gil have explored similar approaches across various industries. Most AI rollup coverage highlights the venture firms pitching the idea, which makes it easy to cast them as the modern Berkshire Hathaways. However, in most cases, these funds are writing ordinary equity checks and moving on; more marketing than execution. The actual heavy lifting of choosing markets, picking between buying, building, or selling, and then threading software into messy workflows to build an actual company sits with founders.

Lessons of History

Some of the most successful companies in modern business history scaled through disciplined, repeatable acquisitions. These companies, often referred to as “serial acquirers”, built economic engines by identifying fragmented industries, deploying capital into overlooked assets, and extracting long-term value through operational leverage and defensible positions.

At a high level, acquirers typically fall into two categories: strategic and financial. The former are those who expect to unlock synergies through vertical or horizontal integration, for example, through shared procurement, labor utilization, pricing, or distribution. The latter are capital allocators focused on buying durable, cash-generating businesses with minimal integration, letting them operate autonomously. However, many successful acquirers sit somewhere in the middle, combining operational alignment with disciplined capital deployment.

One of the earliest and clearest examples of serial acquirers is Waste Management, founded by Wayne Huizenga, Dean Buntrock, and Larry Beck in 1968. Huizenga, who had previously launched a small garbage hauling business in Fort Lauderdale with just one used truck and $5K in borrowed capital, scaled the company by acquiring dozens of small, independent operators. By the time Waste Management went public in 1971, it had completed over 130 acquisitions, consolidating a fragmented industry of small, independent haulers. The company has continued expanding and was acquired by USA Waste in April 1998, which assumed the seller’s name. As of June 2025, Waste Management is North America’s largest waste disposal company, bringing in over $20 billion in annual revenue and operating across the entire waste supply chain, including collection, landfill, and recycling.

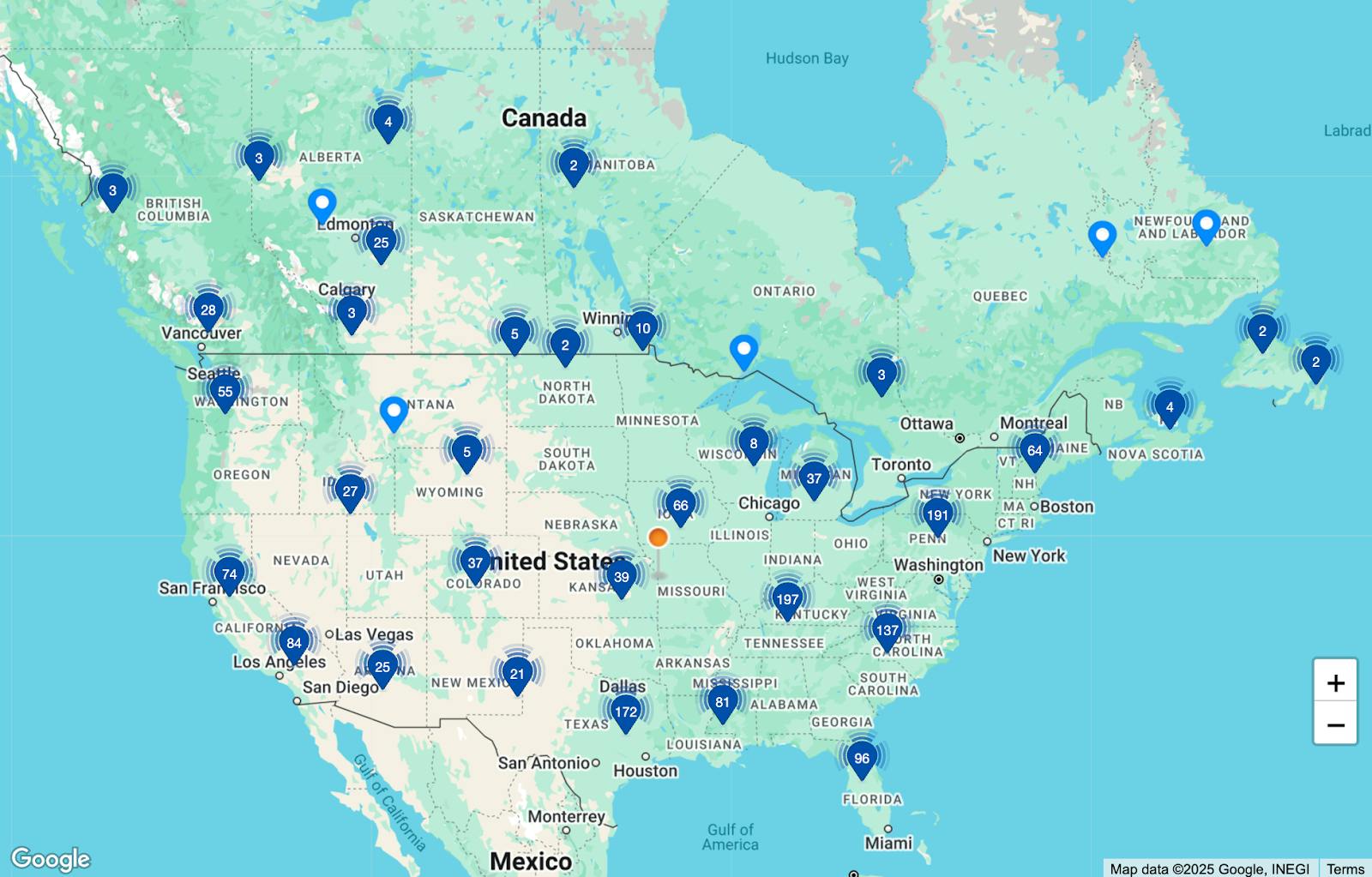

United Waste, one of the companies Waste Management acquired for $2.2 billion in 1997, was also a consolidator in the garbage hauling industry. Started by former oil trader Brad Jacobs in 1989, United Waste focused on rural areas in states like Kentucky and Michigan, which were largely ignored by larger national players. Following the sale, Jacobs launched United Rentals, a construction equipment rental business. Just like Jacobs’ previous company, United Rentals was a serial acquirer from the beginning, programmatically buying up small shops across the US, and eventually becoming the largest equipment rental company in the world.

Source: United Rentals

Jacobs didn’t stop there. He went on to build XPO Logistics, and later spun off GXO and RXO, completing over 500 acquisitions across eight of the companies he founded. A rare M&A serial entrepreneur, Jacobs made acquisitions the cornerstone of his playbook. His approach was relatively simple but highly effective: target industries that are large, fragmented, and slow to modernize; buy companies at attractive multiples; and then standardize operations to unlock value. As Jacobs noted:

“The easiest way to create tremendous shareholder value is to buy businesses at profit multiples lower than the multiple his own stock trades at, and then significantly improve those businesses.”

While companies like Waste Management and United Rentals built value by integrating acquisitions into a centralized operation, another group of serial acquirers has demonstrated that integration isn’t always essential to value creation. Rather than extracting synergies through economies of scale, these firms focused on building portfolios of independently run businesses, emphasizing autonomy over consolidation. Their success stems from repeatable underwriting, a focus on long-term cash generation, and a commitment to preserving what already works.

Berkshire Hathaway, led by Warren Buffett, starting in 1965, is perhaps the most well-known example of a financial serial acquirer. Berkshire’s strategy has always centered on acquiring fundamentally sound businesses with durable moats, capable management, and predictable cash flows. Its portfolio spans a diverse range of industries, including insurance (GEICO), railroads (BNSF), manufacturing (Precision Castparts), utilities (PacifiCorp), and consumer goods (See’s Candies, Dairy Queen). Berkshire provides capital and occasionally strategic counsel, but rarely intervenes in day-to-day operations. This decentralized model is enabled by a deep trust in local operators and a long investment horizon, holding companies indefinitely.

Riches in the Niches

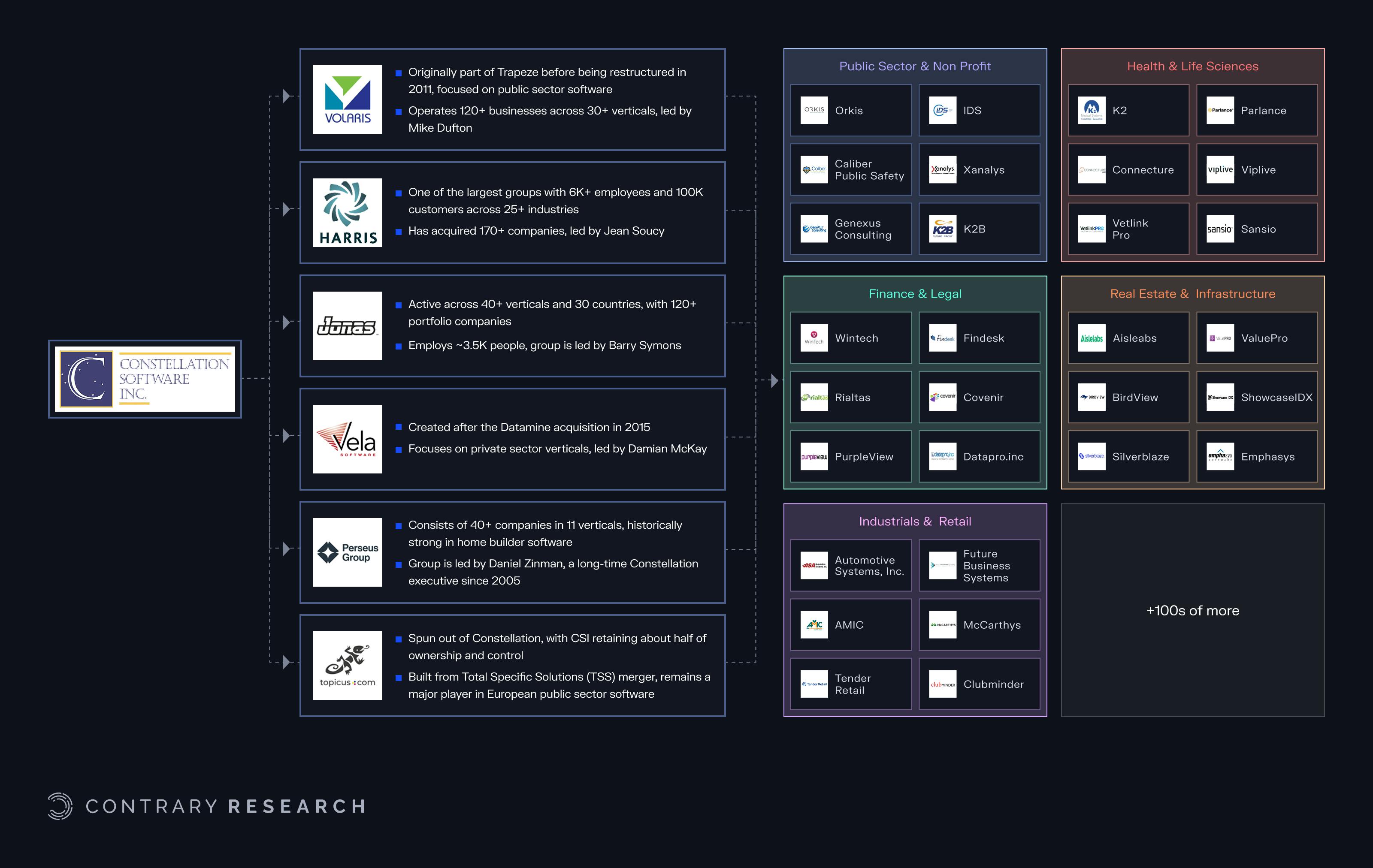

In 1995, Mark Leonard launched Constellation Software with $25 million in capital, backed by Ontario’s municipal pension fund and a handful of colleagues. Inspired by Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger of Berkshire Hathaway, Leonard’s goal was to become the best buyer and permanent holder of vertical software companies in the world. Constellation’s first acquisitions were Trapeze (public transit scheduling) and Harris Computer Systems (utility billing software), both of which were portfolio companies of Ventures West, Leonard’s prior firm.

As of August 2025, Constellation owned over 1K businesses organized into six operating groups, many of which were once acquisitions themselves. Each group specializes in a handful of verticals and conducts its own M&A, growth, and product decisions. Headquarters sets capital allocation policies, high-level targets, and internal guardrails, but otherwise delegates everything. Once a platform is established, managers are far better positioned than HQ to identify, evaluate, and acquire new targets. This gives Constellation surface area and speed in fragmented, underserved markets that a centralized firm could never match. This autonomy is also attractive to founders, especially those looking for a liquidity event, but also to preserve their team and autonomy.

Source: Constellation Software; Contrary Research

Constellation does not integrate companies culturally or operationally; only financially. As Leonard explained in his 2016 annual letter to shareholders:

“CSI's strategy is to be a good owner of hundreds (and perhaps someday thousands) of growing autonomous small businesses that generate high returns on capital. Our strategy is unusual. Most CEO's of public companies would rather run a single big business - perhaps two or three big businesses, but rarely 200 businesses. They expect (or hope) to get above average returns on capital by pursuing 7 economies of scale and by crushing or acquiring their smaller competition. ‘We are #1 in this large and growing market’ is their normal aspirational paradigm. It's also a formula with which shareholders, analysts and boards are comfortable. We recognise that economies of scale, centralised management and world class talent competing in large and growing markets can be a great business-building formula. But, it isn't what we do."

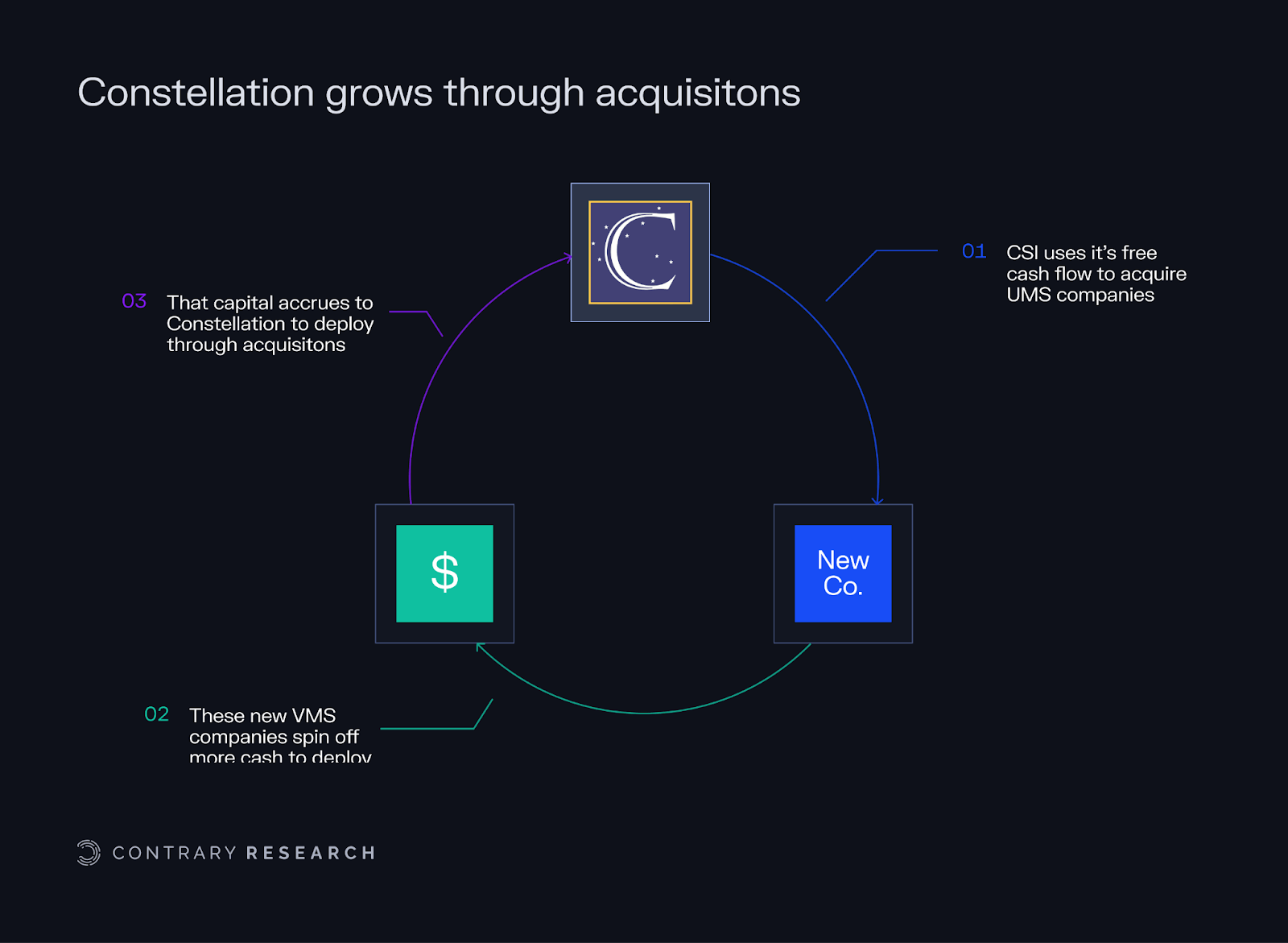

Constellation turns free cash flow from its vertical market software businesses into fresh acquisitions, folds those companies in with minimal disruption, and then channels the new cash they generate back into the same cycle. This disciplined loop has compounded value for decades. Constellation has grown from $165 million in 2005 revenue to over $10 billion in 2024; the company’s stock price has grown over 150x in the same time frame.

Source: The Generalist; Contrary Research

Even though SaaS has reshaped much of the software landscape, the majority of Constellation’s portfolio still runs on-premise software. Arguably, this isn’t because it’s better for the customer, but because it makes their products harder to replace. SaaS, with its portability and lower deployment friction, can reduce switching costs and invite competition. On-premise systems, in contrast, often tie deeply into operational workflows and legacy infrastructure, making transitions costly, risky, and time-consuming. The result is a software environment where customer lock-in is maximized and disruption is minimized. As Constellation’s former CFO Barry Symons put it:

“What we do at Constellation, for most of our existing customers, in most of our verticals is real enterprise resource planning. All the ERP mission-critical-type software. And if you ever switched over some critical type of software, it’s not a fun experience. Root canals are much better — I’d much more recommend that. So our customers really don’t want to leave us — so as long as we don’t give them reasons to.”

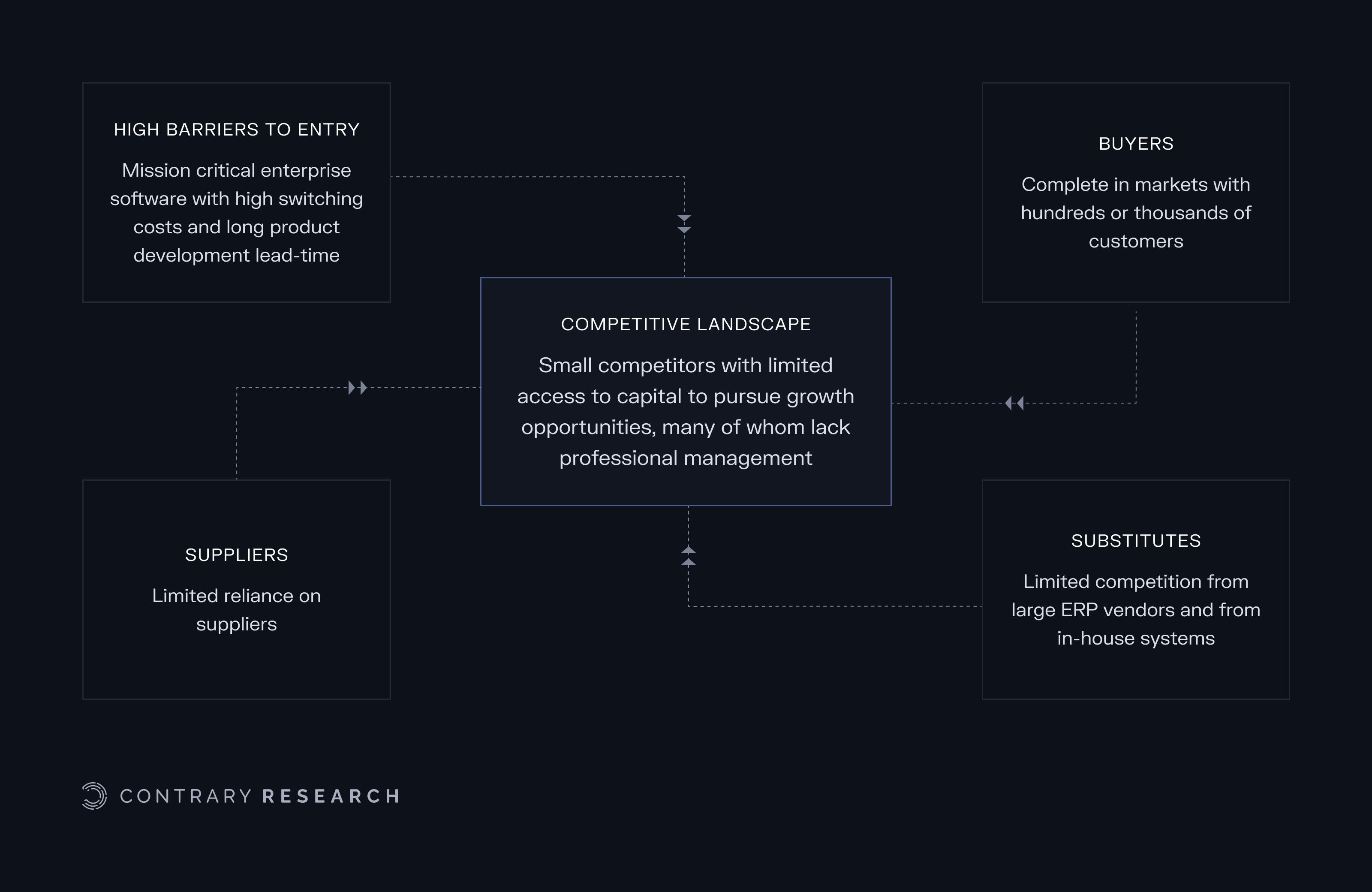

Constellation’s businesses operate in some of the most defensible niches in all of software. Their products are almost always mission-critical, often serving as the ERP backbone of a business or public agency. Most verticals they enter have only one or two credible vendors, and once a customer adopts a solution, switching becomes a logistical and operational nightmare. These markets are small and saturated, which deters well-funded competitors from entering. The software itself typically represents a tiny fraction of the customer’s total cost base, yet plays an outsized role in day-to-day operations. As such, price competition rarely works, and incumbents retain control for decades.

This creates a unique dynamic: the earlier you enter a vertical, the more defensible your position becomes. A startup might offer a sleeker UI or modern APIs, but it would need to overcome enormous switching inertia and justify that effort in a market too small to attract much, if any, venture capital investment. When combined with strong gross margins, low churn, and perpetual ownership, this strategy has yielded one of the most durable and compounding models in the history of software.

Source: Constellation Software; Contrary Research

What began in 1995 with a $25 million check and a handful of acquisitions has transformed into one of the most prolific compounding engines in software history. Since its IPO in 2006, the company has grown at a ~30% CAGR. Its strategy of acquiring and holding hundreds of vertical software businesses has proven that scale, stability, and superior capital allocation can rival innovation when executed with discipline.

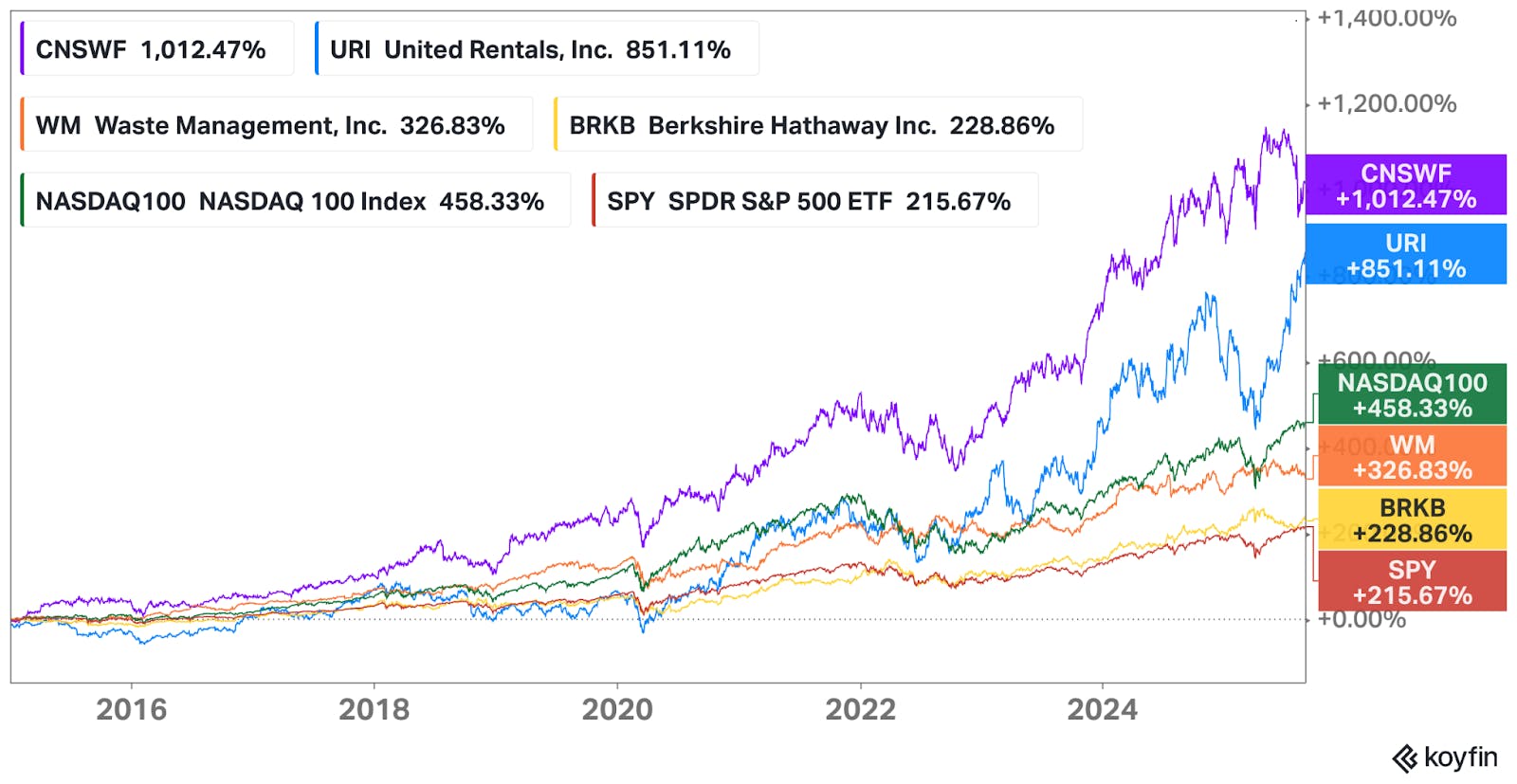

Over the past decade, public markets have rewarded several disciplined acquirers. Constellation Software, United Rentals, and Waste Management have significantly outperformed the S&P 500 and NASDAQ 100. To some degree, these returns indicate the market’s appreciation for capital efficiency, recurring revenue, and repeatable playbooks. Additionally, companies that pursue acquisitions systematically tend to outperform those that acquire infrequently.

Source: Koyfin

For decades, this model was largely followed by traditional corporate buyers and private equity firms. But in the late 2010s, venture capital tried its hand at a similar playbook. Rather than investing solely in technology-first startups, some venture firms began backing companies whose core strategy resembled private equity: acquiring and operating traditional businesses.

Enter VC

This shift began with the rise of venture-backed ecommerce aggregators. Following the rise of third-party merchants on Amazon and Shopify before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, a wave of startups emerged to consolidate digital storefronts. Their pitch was to acquire high-performing product brands, apply centralized logistics and advertising infrastructure, and scale profitably. The most prominent of these was Thrasio, which was founded in 2018 and raised over $3 billion in debt and equity. Others, including OpenStore, Berlin Brands Group, and Pattern Brands, pursued similar models.

At its peak in October 2021, Thrasio was valued at nearly $10 billion and owned hundreds of merchants, completing an average of 1.5 acquisitions per week. By May 2022, the business had conducted its first round of layoffs and had changed leadership. Many of its products experienced sales declines post-acquisition, due to operational missteps and shifts in consumer behavior as pandemic-driven demand subsided. Most critically, the business was built on cheap debt during the zero-interest-rate period. As interest rates rose and margins compressed, Thrasio found itself burdened with high debt service costs and deteriorating cash flows. The company ultimately canceled its planned SPAC IPO and filed for bankruptcy in February 2024. The collapse highlighted the limits of applying a growth-stage venture playbook to an operationally intensive acquisition model, and became a cautionary tale of how financial engineering alone cannot substitute for durable differentiation.

However, not all venture-backed rollups followed this path. A number of startups pursued differentiated models and selective acquisitions, rather than racing to scale through volume alone. One such example is Teamshares*, which has approached serial acquisition by productizing employee ownership. Founded in Brooklyn in 2019, the company acquires small businesses from retiring owners, typically in traditional, fragmented industries like commercial refrigeration, apparel manufacturing, and commercial services, transitioning them into employee-owned companies via an ESOP (employee stock ownership plan). Teamshares appoints trained presidents to run operations and gradually dilutes its own equity to reach 80% employee ownership over time. Unlike traditional private equity, it doesn’t plan to resell these businesses. Instead, it provides a fintech platform that can monetize the network through proprietary tools like neobanking, insurance, and credit products. As of May 2025, Teamshares had completed over 100 acquisitions and raised $245 million in funding, with an ambition to build a network of over 10K small businesses over time.

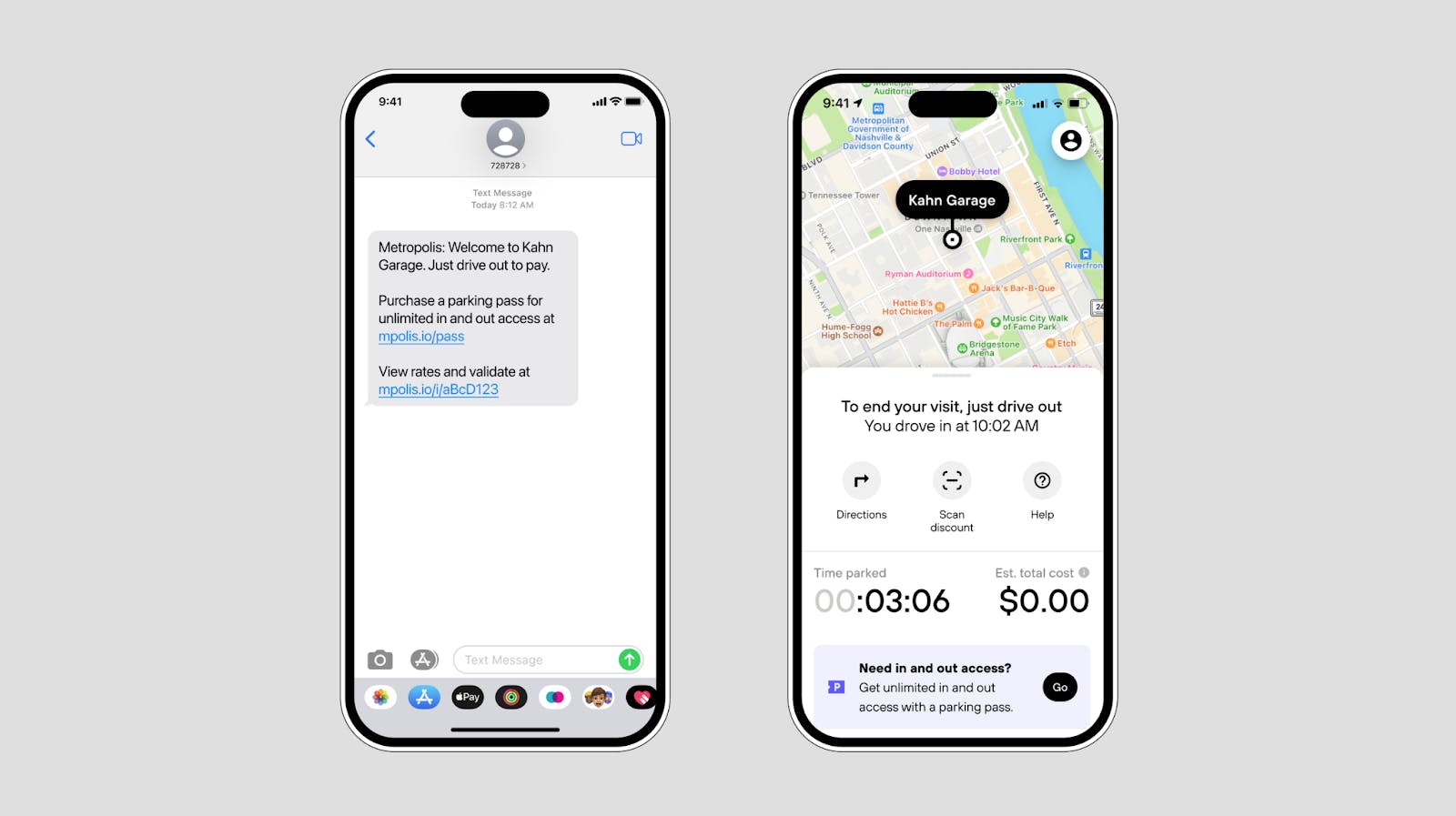

While Teamshares differentiates with its ownership structure for small businesses, Metropolis illustrates another approach by leveraging technology and acquisitions to modernize a fragmented, asset-heavy industry. Founded in Los Angeles in 2017 by Alex Israel, Metropolis uses an AI and computer vision stack to enable frictionless entry and exit for parking lot customers, enabling them to drive in, be identified via license plate cameras, and get automatically charged upon exit.

Initially, Metropolis pursued a traditional B2B go-to-market model, partnering with parking facility owners and operators to layer in its technology, but the team encountered the structural limitations of the industry. Parking operators worked under long-term lease or management agreements, and sales cycles were often slow-moving and relationship-driven. In Israel’s words, the company had early product-market and unit economic fit, but struggled to achieve go-to-market fit. To overcome this, Metropolis pursued an alternative – rather than sell to incumbents, it would buy them.

Source: Metropolis

The company’s first major acquisition was Premier Parking, a Nashville-based operator managing over 600 garages. By acquiring Premier in 2022 and deploying its technology across the portfolio, Metropolis gained both operational leverage and credibility. Customer experience improved, and asset owner margins expanded. Encouraged by these results, Metropolis’s investors, which included Slow Ventures, Starwood Capital, and Silver Lake, supported a far larger bet. In October 2023, the company raised $1.7 billion in debt and equity to acquire SP Plus, the largest parking operator in North America, for $1.5 billion.

In the 2023 financial year, SP Plus managed 3,384 commercial locations and over 150 airports, generating $1.8 billion in annual revenue but only $31 million in net income. Before the acquisition, SP Plus had pursued modernization through its own small acquisitions, including US-based frictionless parking startup DiVRT, enforcement software provider Roker, and AeroParker in the UK. Metropolis now sits atop a fragmented but sprawling network of urban mobility infrastructure, with the mandate and financial means to consolidate and modernize it.

These examples illustrate how venture-backed rollups tested the boundaries of traditional private equity and technology-first playbooks. Examples like Thrasio demonstrate that high-volume acquisition is not enough. Others, like Metropolis and Teamshares, demonstrate a more measured approach to specific implementations of the serial acquirers playbook. But before drawing broader conclusions, it’s worth zooming out to understand the evolution of vertical software itself.

AI & The Vertical Stack

The emergence of SaaS in the 1990s made it possible to deliver core business tools over the internet, eliminating the need for users to manage installation, upgrades, or maintenance. Some of the earliest and most influential examples were NetSuite, Salesforce, and Concur. Founded by former Oracle executive Marc Benioff in 1999, Salesforce pioneered the idea that core business functions like customer relationship management (CRM) software didn’t need to be hosted on in-house servers. Instead, they could be delivered entirely through the browser, with automatic updates, lower upfront costs, and no IT overhead. This radically changed how software was bought and sold, and established a template that would eventually expand into almost every business category.

Eventually, founders of SaaS companies realized that the biggest pain points weren’t always shared across companies. Every industry operates a little differently. A trucking company, a spa, and a law firm each have distinct workflows, compliance needs, and customer expectations. Unlike horizontal SaaS, which aimed for broad applicability, vertical SaaS companies embedded themselves deeply into the specific logic and language of one industry. Hence, there wasn’t going to be one winner-takes-all solution. Instead, hundreds of specialized tools could thrive in smaller, less competitive markets. But at the same time, these smaller markets weren’t always attractive to venture capitalists. Most VCs were focused on multi-billion-dollar markets with high growth potential, not companies serving tow truck fleets or retirement homes.

Across the landscape of vertical software, founders have taken different paths to scale. Some chose to sell early, finding lasting homes under Constellation, private equity platforms, or other acquirers. Others stayed independent, reinvesting in product, expanding across adjacent workflows, and gradually evolving into the digital backbone of their industries. In doing so, they built enduring, multi-billion-dollar companies rooted in deep vertical expertise. For example:

ServiceTitan became essential infrastructure for the trades, streamlining scheduling, dispatch, payments, and more for HVAC, plumbing, and electrical contractors.

Toast began with point-of-sale terminals for restaurants, then layered on payroll, payments, inventory, and lending.

Mindbody focused on wellness studios, helping them manage bookings, memberships, and customer engagement, becoming the central nervous system of boutique fitness.

Shopify, while technically could be considered horizontal, succeeded by deeply understanding the needs of independent merchants and offering an all-in-one ecommerce stack.

Procore digitized the messy world of construction project management, becoming the default software layer for contractors and builders.

Epic Systems took the long road in healthcare, quietly building a closed but powerful EMR ecosystem used by most major US hospitals.

Each one started in a narrow niche. Over time, they earned the right to expand into adjacent features such as finance, infrastructure, and even entire marketplaces. Their stories show that when done right, vertical SaaS can become a foundation for an enduring business, not just a stepping stone to a broader market.

Source: Slow Ventures; Contrary Research

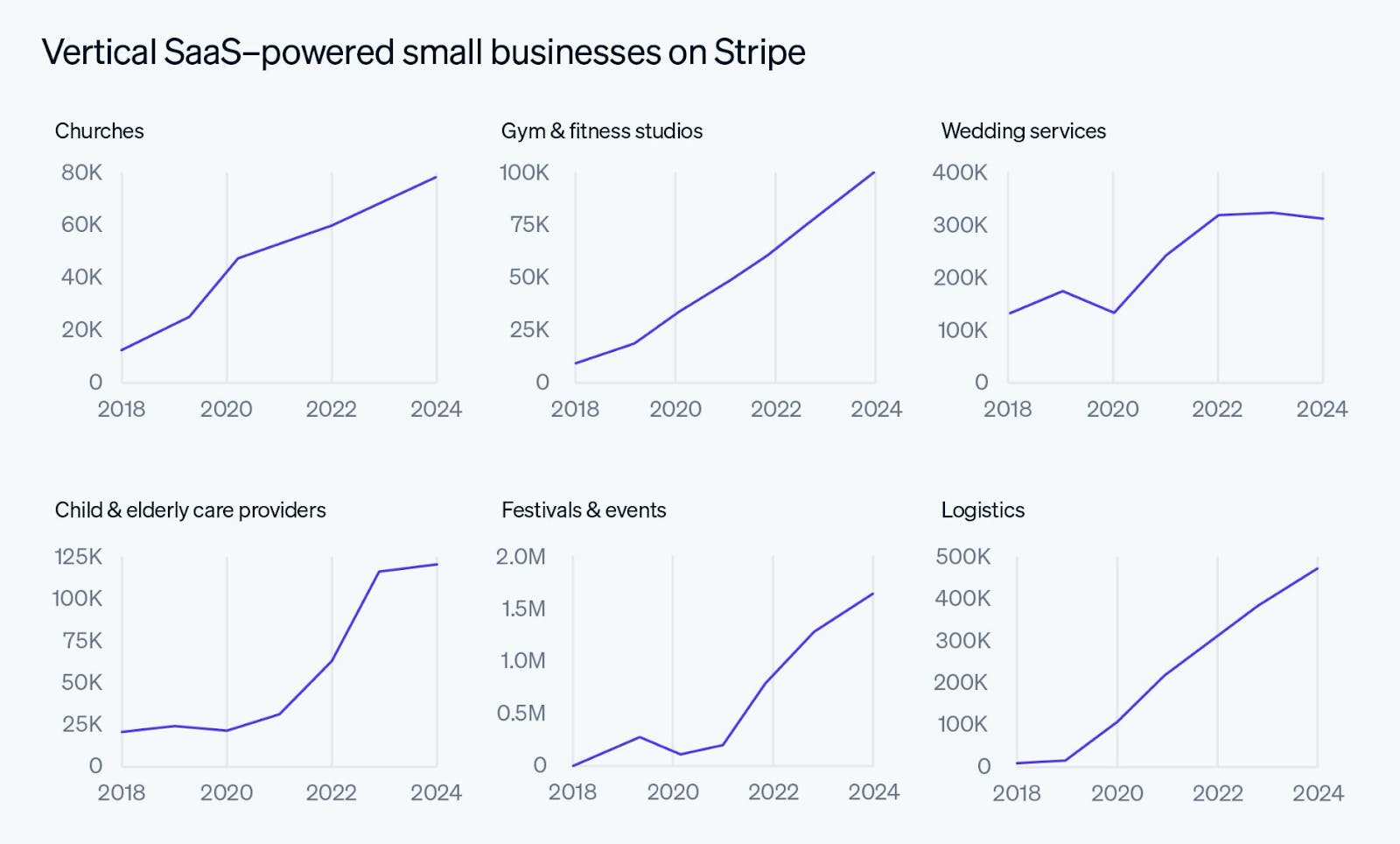

In its 2024 annual letter, Stripe observed a surge in newly established independent businesses using its payments solutions, largely attributing this to the rise of vertical SaaS platforms. As an example, from 2005 to 2017, the number of independent pizzerias in the US declined as franchises such as Domino’s, Pizza Hut, and Hunt Brothers dominated. That trend reversed in 2017, and by 2023, more new pizzerias opened than in any prior year. This was because vertical SaaS platforms like Slice provided pizzerias with everything they need to compete with large franchises: a website, payment system, marketing tools, custom pizza boxes, and more.

Such tools give independents the infrastructure of a franchise without giving up control. This way, SaaS becomes a distribution platform for entrepreneurship. As Stripe put it:

“Today, 60% of all small businesses in America use vertical SaaS platforms to help run their business. Arborists use SingleOps, towing companies use Traxero (which even has a state-of-towing podcast), and liquor stores use Transformity’s AI-driven inventory management. If you want to open a med spa, Moxie can get you going in 30 days. Independent law firms use Clio; pool cleaners use Skimmer; churches use Planning Center, Tithe.ly, Subsplash, or Pushpay; synagogues use Shulware; truck dealerships use Procede; and funeral homes use Meadow Memorials or Tribute Technology.”

Source: Stripe

What Changes With AI

In November 2022, OpenAI released ChatGPT. Within two months, the application reached over 100 million users, which made it the fastest-growing software product in history. While initially framed as a chatbot, it quickly became clear that LLMs, the underlying technology, could be used as a general-purpose interface for a broad range of cognitive tasks.

Source: Contrary

This release triggered widespread experimentation across the software industry, and many B2B companies began revising their product strategies to incorporate generative AI. In vertical SaaS, responses varied. Some companies integrated OpenAI’s models into existing features, while others began building new products around AI capabilities.

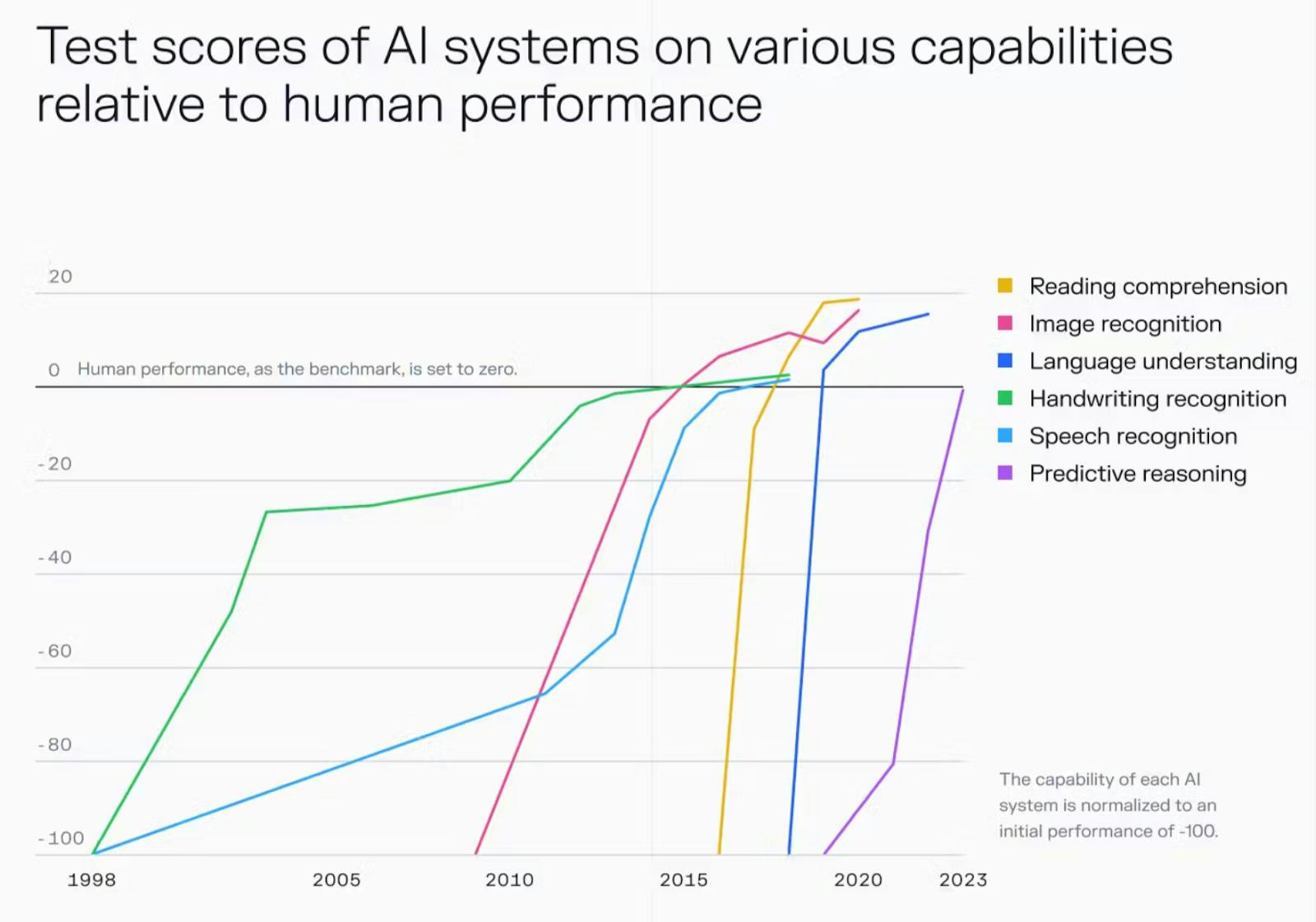

Traditional SaaS platforms transformed workflows by digitizing them, replacing paper forms and manual processes with structured, cloud-based interfaces. This made tasks faster, more organized, and easier to track. Tools like CRMs and ERPs captured data, standardized inputs, and improved collaboration across teams. LLMs extend this trajectory by not just documenting or organizing work, but performing it.

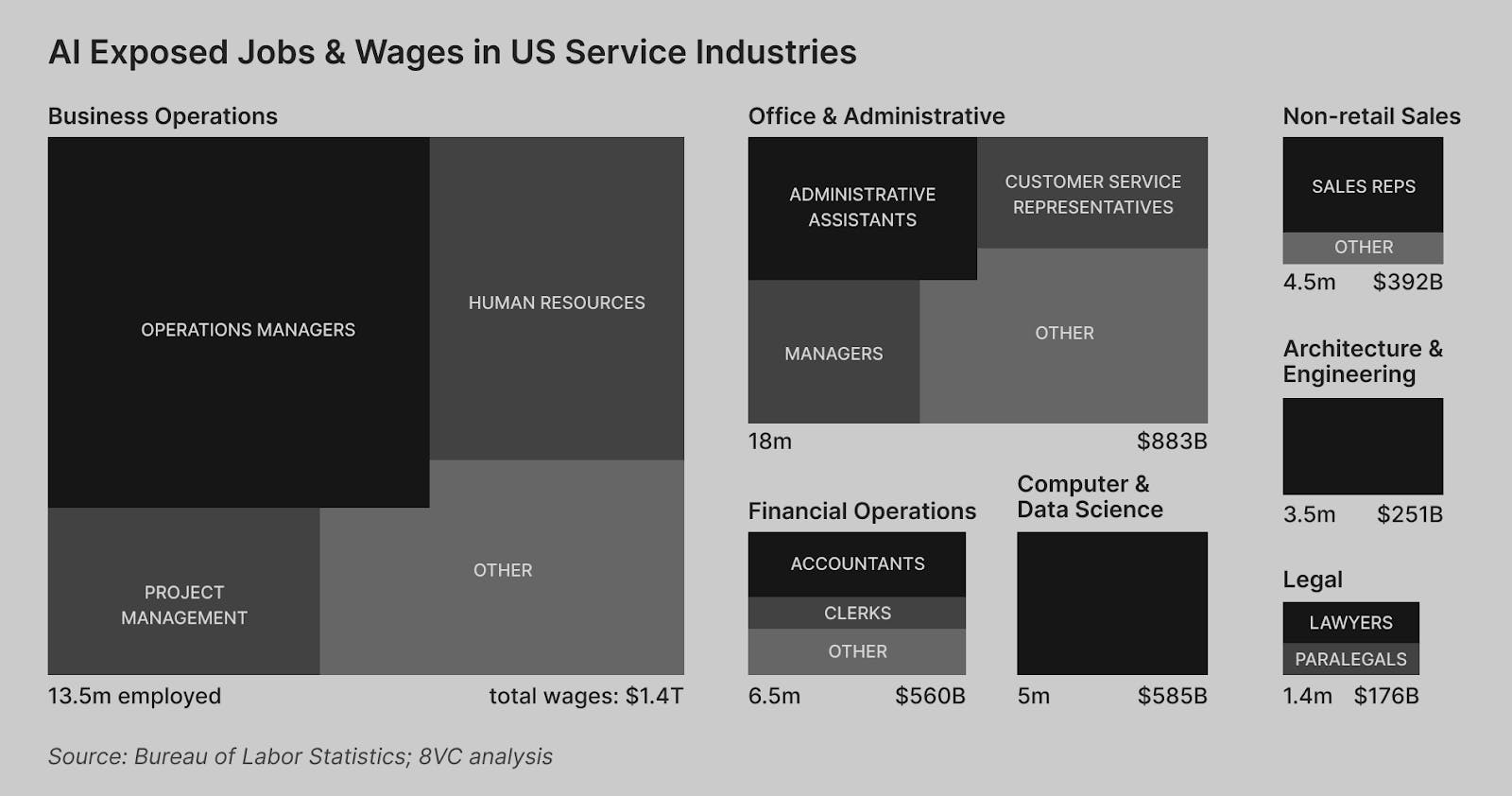

This transition has important implications for vertical markets. Many industry-specific workflows, such as insurance claims processing, freight brokerage, or medical billing, were historically labor-intensive, with limited software penetration due to the high degree of complexity and customization required. By automating execution rather than just record-keeping, AI-native systems expand the total addressable market, capturing not only software spend but portions of the underlying labor cost base.

Source: a16z; Contrary Research

One prominent early example was Thomson Reuters’ acquisition of Casetext for $650 million in June 2023. Casetext developed CoCounsel, an AI legal assistant built on OpenAI’s models, capable of conducting legal research, drafting memos, reviewing contracts, and more. The acquisition signaled that generative AI could move beyond consumer novelty into critical, professional workflows, offloading high-cost labor in tightly regulated industries. Rather than simply indexing legal documents, tools like CoCounsel perform substantive legal work, redefining the boundaries of what enterprise software can do.

Source: 8VC

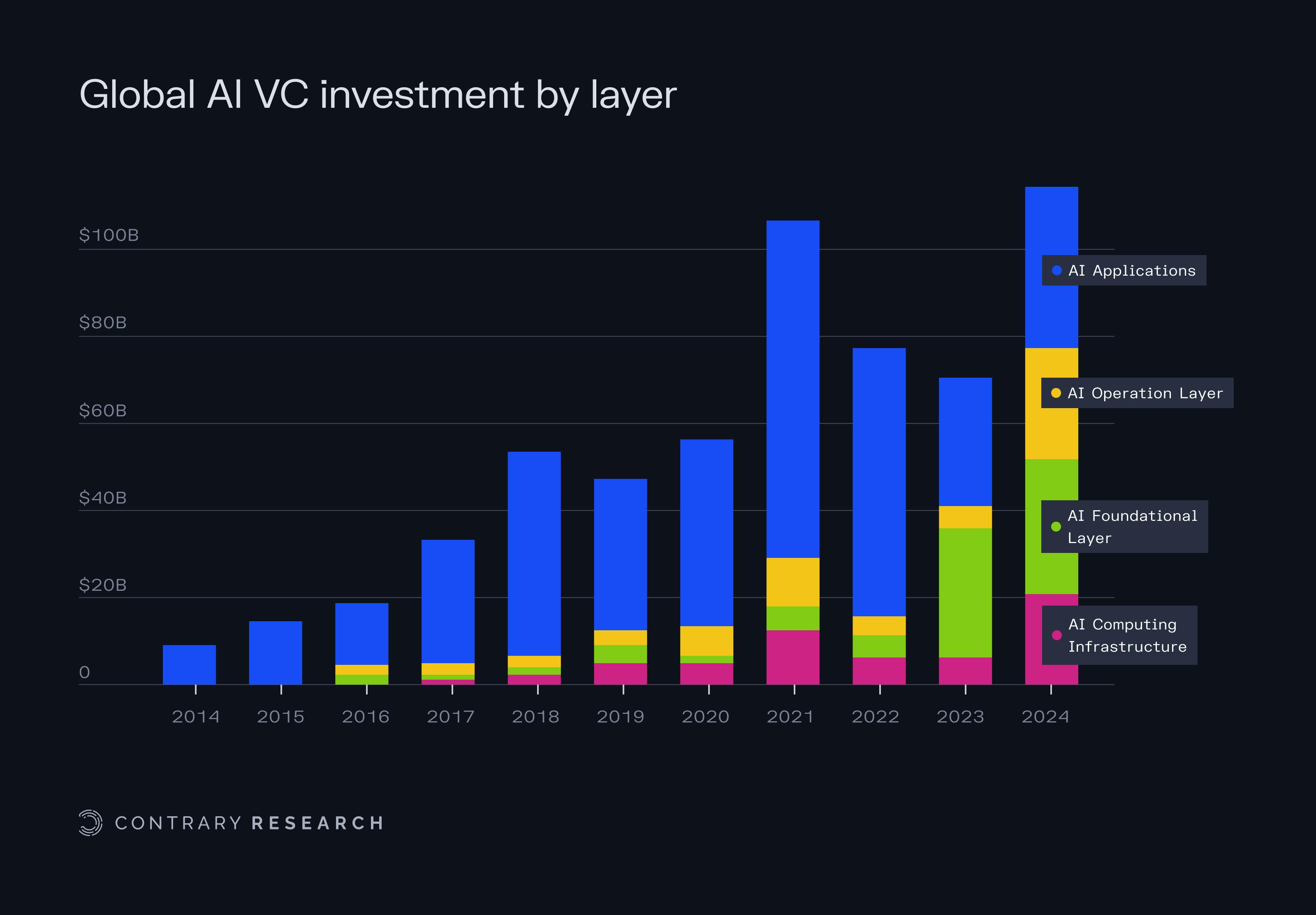

As more industries adopt similar capabilities, the market for vertical software expands, and the small markets dominated by players like Constellation Software are no longer that small. In 2023, the total wages paid to workers in the US amounted to over $11 trillion. Some estimates indicate that over $4 trillion of these wages could be impacted by AI, whether augmented or automated. The funding environment has shifted to reflect the opportunity. In 2024, AI startups raised approximately $110 billion in venture financing, a 62% increase from the prior year. By contrast, total private technology investment declined by 12% year-over-year, indicating a concentration of capital toward AI-native companies.

Source: TechCrunch; Contrary Research

Deployed Intelligence

Investment is surging into AI, yet value is only realized when the technology becomes part of daily operations. The constraint has moved from building bigger models to embedding them in real-world workflows, an exercise that looks very different from shipping traditional SaaS.

Deploying AI is not the same as shipping software. While traditional SaaS tools are typically integrated through onboarding, training, and configuration, AI systems often require deeper immersion. Understanding real-world workflows, or sometimes rewriting them entirely, iterating with users, and building guardrails over time. Palantir, one of the earliest AI-native companies, didn’t succeed through a self-serve product. Instead, it maintained teams of “forward deployed engineers” who embedded directly within client organizations. Their job was to observe, interpret, and abstract operations into reusable software logic. Over time, these abstractions informed product improvements and drove scale. The initial cost was high, but the payoff was deeper defensibility and tighter operational integration.

In this model, AI is best understood as a new labor class, which is contextual, capable, and increasingly general, but still requiring management. Instead of just buying software out of the box, you’re effectively hiring AI, training it, monitoring its output, and adapting your workflows to accommodate it. Integration success depends less on model quality and more on thoughtful deployment; how the model is wrapped in the interface, aligned with decision logic, and embedded into daily operations. The opportunity, especially in vertical software, is to rebuild workflows from scratch, instead of automating established ones.

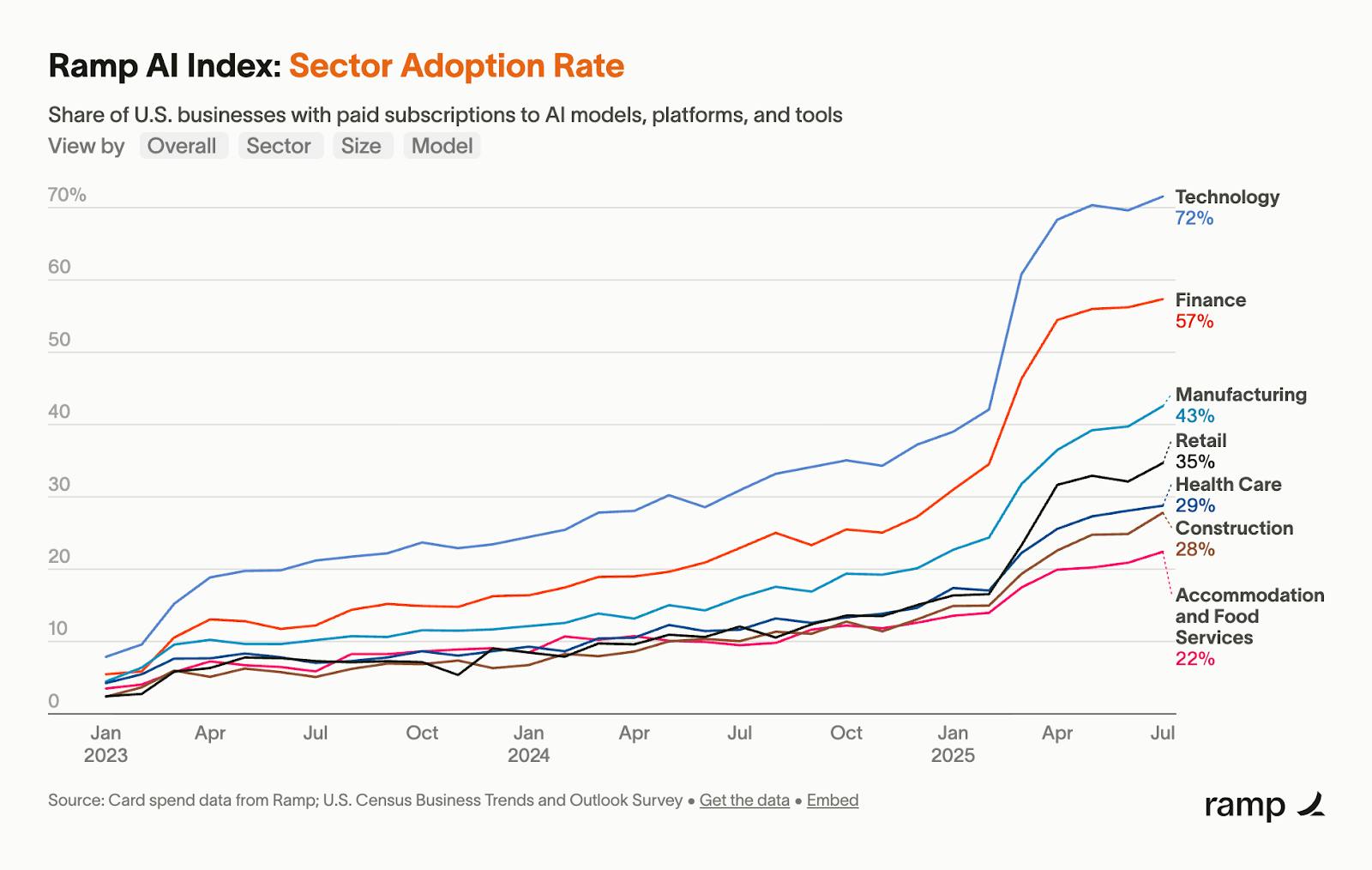

According to Ramp’s* 2025 AI Index, 72% of technology firms had paid subscriptions to AI tools, compared to just 28% in construction and 22% in accommodation and food services. This disparity highlights both the pace of adoption and the structural constraints across verticals. Moreover, usage does not necessarily imply transformation. While AI spend is rising, it’s difficult to assess whether these subscriptions translate into meaningful margin improvement.

Source: Ramp

Despite widespread access to foundation models, most non-technology companies are unequipped to deploy AI effectively. AI deployment requires interdisciplinary fluency across engineering to build interfaces, product design to map decision points, domain knowledge to guide logic, and change management to drive adoption. Many firms in traditional industries expect AI to behave like plug-and-play SaaS, but AI systems demand new workflows and active oversight. They behave probabilistically, improve with feedback, and require iterative tuning.

This gap is reopening the case for vertical integration. Many full-stack companies of the 2010s struggled due to labor bottlenecks and low-margin services, but today, AI could change the economics. With agents performing a growing share of the work, human-intensive operations become lighter, and margins improve. As Y Combinator put it in a 2025 Request for Startups:

“Suppose you believe that LLMs are now able to automate a lot of legal work. There are two things you might do with that idea. You could build an AI agent and sell it to law firms. That's what most people do. Or, you could start your own law firm, staff it with AI agents, and compete with the existing law firms.”

Two Paths to Capture the AI Margin in Vertical X

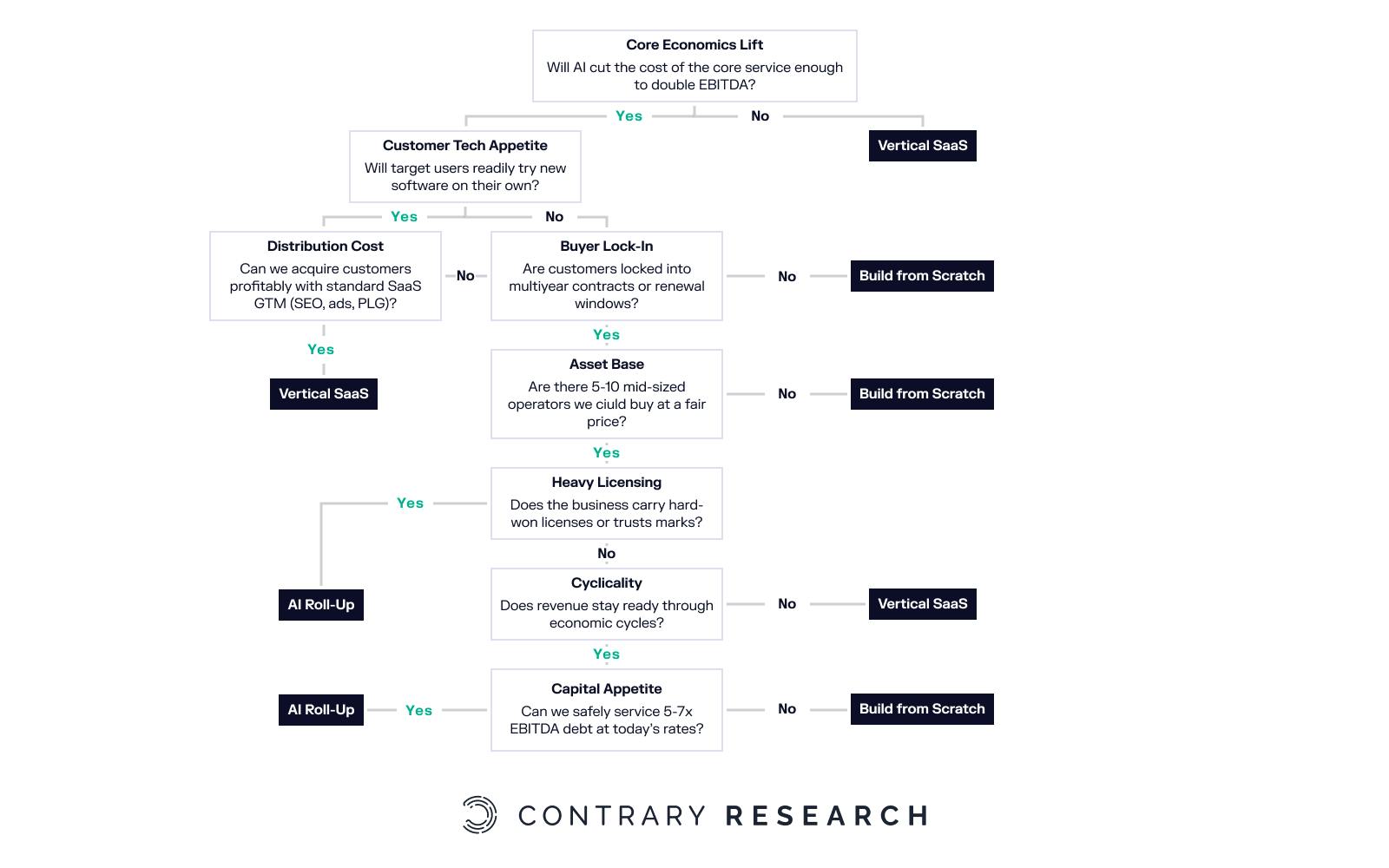

As AI begins to reshape workflows in traditional industries, builders face a choice in how to capture the margin unlocked by automation. There are two primary approaches: selling software to existing operators or becoming the operator directly.

Path 1: Sell Software to the Operator

The first path resembles the traditional SaaS model, though with a modern twist. Companies develop copilots, automation layers, or agent-powered tools and distribute them to existing operators. This approach is typically faster to execute and more scalable, particularly in industries where incumbents are difficult to displace but open to performance-enhancing tools that fit within their existing workflows. Crucially, this model assumes that the end customer has the internal capability to operationalize software, deploy it effectively, train staff, manage exceptions, and adapt workflows accordingly.

In practice, distribution remains a major friction point. Many verticals still rely on legacy systems, have low software literacy, or lack the resources for change management. Even when the product delivers clear value, adoption can be slow due to the effort required to retrain teams and rewire existing processes. Moreover, competition in this segment is intense. In nearly every vertical, a growing number of AI-powered software vendors are pitching similar benefits to the same customer base, making differentiation and retention more difficult.

Path 2: Build or Buy the Operator

The second path is to go beyond software and build or acquire the service provider itself; operating the business, embedding AI directly, and removing all dependency on customer-side integration. This approach is slower to stand up, significantly more operationally intensive, and requires more upfront capital. But it also promises greater control and, ultimately, higher margin capture.

When you own the service layer, you can install your tool directly, and you don’t need to convince a customer to adopt it. You can redesign workflows, measure impact precisely, and iterate without waiting for customer feedback. In return, your business gains increased defensibility and stronger alignment between technology and service delivery.

In the age of AI, whichever path founders and investors choose, whether selling software or owning operations, both require rethinking the traditional venture playbook. In many cases, AI demands new commercialization models, new organization structures, and possibly new forms of ownership.

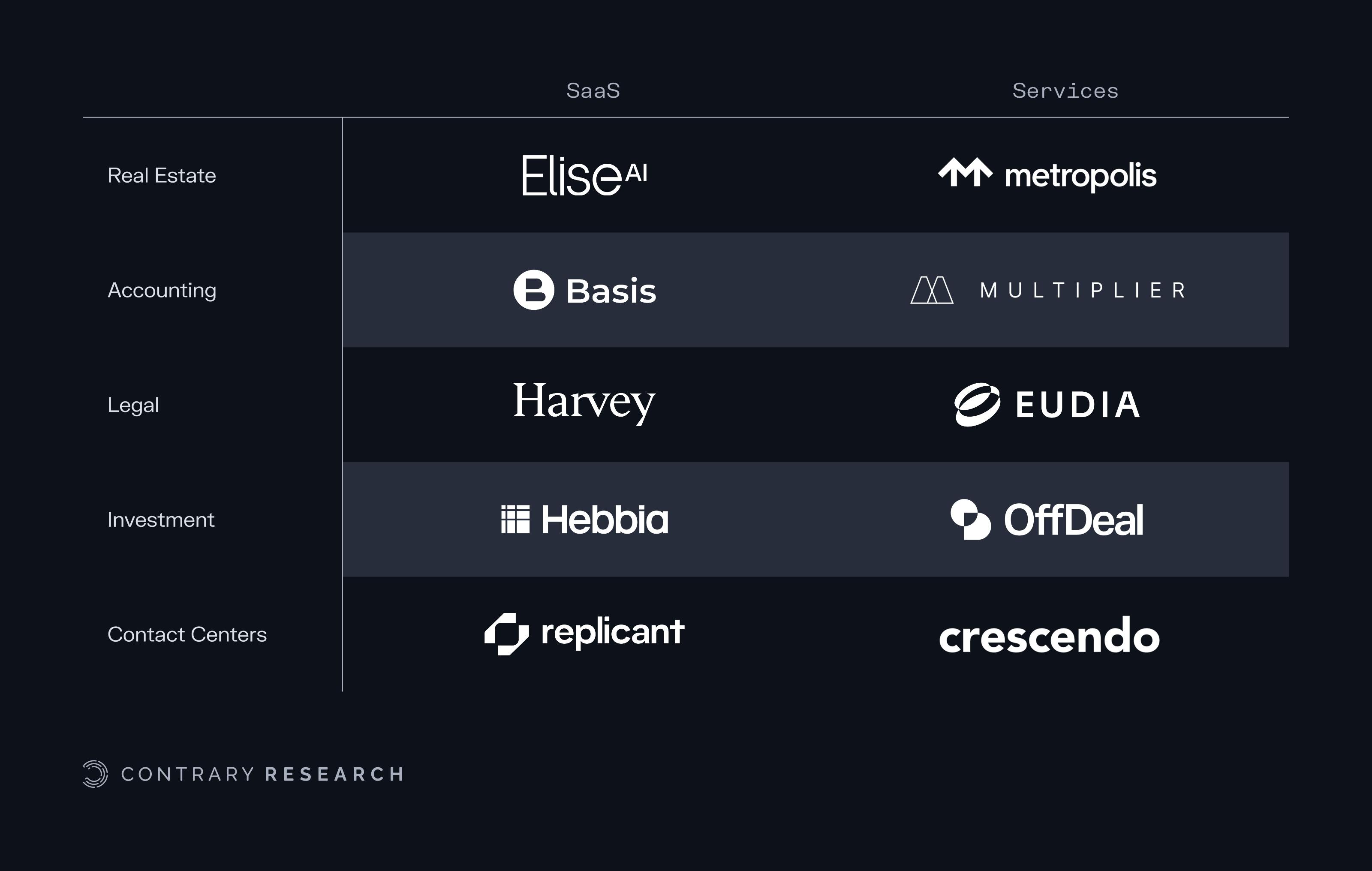

Case Studies

Across a number of traditional sectors, companies are leveraging one of the three models of AI deployment: (1) selling to customers, (2) buying existing operators, or (3) building full-stack AI-native companies from scratch. In some cases, a company may start with one approach, but gradually shift into another after expanding its offerings. Each model has tradeoffs. The right choice depends on the industry’s structure, the durability of the product, and the team’s execution capabilities.

Source: Contrary Research

Real Estate

EliseAI: Automation platform for property managers across mostly residential housing. Starting in tenant communication, EliseAI is a suite of conversational AI agents which integrate into the customer’s property management system and handle tasks like tour scheduling, tenant questions, and maintenance requests. EliseAI sells its product as software, targeting over 350 institutional real estate owners, claiming to automate over 85% of all conversations without human intervention. In an interview in June 2025, co-founder and CEO Minna Song explained that a common pitfall among EliseAI’s customers is trying to layer new technology onto outdated workflows without making structural changes.

Metropolis: Having previously built a parking mobile app, Metropolis founder Alex Israel set out to embed intelligent infrastructure directly into the built environment. Instead of just routing drivers to parking spaces, Metropolis uses proprietary AI and computer vision to enable frictionless entry and exit. Metropolis initially pursued B2B sales to parking facility operators, but the team encountered limitations given long-term lease and management agreements, making sales cycles slow. In Israel’s words, the company had early product-market and unit economic fit, but struggled to achieve go-to-market fit. To overcome this, Metropolis pursued an alternative: rather than sell to incumbents, it would buy them. The company’s first major acquisition was Premier Parking with 600 garages in 2022, gaining both operational leverage and credibility. In October 2023, the company raised $1.7 billion in debt and equity to acquire SP Plus, the largest parking operator in North America, for $1.5 billion.

Wander: A short-term rental platform for premium vacation homes, Wander started with a vertically integrated model, owning and operating properties through a REIT to ensure quality control and a consistent guest experience. However, as interest rates rose and its Credit Suisse-backed financing fell through, Wander shifted away from ownership, closing its REIT and introducing two new models: Wander Operated, where it fully manages homes it doesn’t own, and Wander Branded, where it licenses its software and brand while local operators handle daily management. By May 2025, the company listed over 1K homes across the US and internationally. Wander positions itself as a tech-enabled operator in the high-end travel segment, focused on scale, software, and customer experience without owning physical assets.

Long Lake: Long Lake Management Holdings was founded in 2024 and is focused on acquiring companies across the residential, business, and infrastructure services sectors. Its first target sector was homeowner association (HOA) management companies, where AI tools have resulted in productivity gains of up to 30%. As of January 2025, Long Lake has raised over $600 million from investors, including General Catalyst and Thrive Capital, through its Thrive Holdings vehicle. Long Lake has acquired 18 companies, collectively employing around 1.4K workers. Long Lake’s strategy involves retrofitting its portfolio companies with AI tools, which it expects will bring efficiencies to service operations.

In real estate, AI adoption appears to hinge less on layering a tool over existing workflows and more on reshaping how those workflows operate. While EliseAI is selling software, Metropolis, Wander, and Long Lake own the operational layer, but not the physical assets (parking garages, vacation homes, and HOA-member homes). In each case, the company’s success hinges on the ability to institute change. EliseAI is dependent on its customers’ willingness to rethink the leasing and maintenance process, but Metropolis, Wander, and Long Lake are able to implement change themselves as the operators vs. third-party software.

Accounting

Basis: A New York–based startup founded in 2023 by Matt Harpe and Mitchell Troyanovsky, focused on using AI agents to augment and automate accounting workflows. Basis sells directly to accountants, giving them AI tools that can be directed and customized for specific engagements. Its product is designed to function more like a virtual team than a traditional system, adapting to different client setups and executing actual tasks. The company’s approach is based on a few clear beliefs: that AI agents should do real work, not just answer questions; that workflows must be adaptable to the nuances of each engagement; and that software should act as a partner rather than a replacement. Instead of layering AI on top of outdated processes, Basis encourages firms to reimagine how work gets done, with AI at the center. Its team has already begun deploying with top 100 US accounting firms, reporting up to 30% time savings.

Crete: An accounting platform launched in 2023, acquiring local accounting firms and integrating them into a national network while offering shared infrastructure. Its founders, Jake Sloane and Frank Zhang, operate ZBS Partners, a private equity fund focused on roll-up strategies in industries like home services, veterinary clinics, and IT service providers. In its first two years, Crete has grown to over $300 million in annual revenue and 900 employees. As of August 2025, the company has acquired more than 20 firms to date and is planning to spend over $500 million on additional acquisitions. Crete allows local partners to retain ownership and continue operating their firms, while providing centralized support across HR, finance, compliance, recruiting, and operations. It also develops internal AI tools in partnership with OpenAI and Thrive Capital’s engineering team. These tools are designed to support accounting workflows such as audit testing, memo writing, and data mapping. Early implementations have helped Crete-owned firms reduce manual work and free up time for higher-value tasks, to improve service quality and increase firm capacity without increasing headcount.

Multiplier: Founded in 2022 by former Stripe executive Noah Pepper, Multiplier began by building AI software for tax firms before realizing the real leverage was in rethinking how firms operate. Instead of taking its software to market, Multiplier pivoted to acquiring existing accounting firms and embedding AI deeply into their services. Its first acquisition, Citrine International Tax, quickly demonstrated the approach – by integrating AI across core tax and compliance work, Citrine doubled its margins and scaled its service capacity, with just 12 team members.

In accounting, AI adoption doesn’t seem to hinge on adding a tool to existing practices so much as reshaping how firms operate from the inside out. Basis shows how AI delivers its biggest gains when it becomes a core part of the workflow, acting as a digital team rather than a surface‑level feature. Crete and Multiplier point to a shift in approach, away from selling standalone software and toward acquiring firms where AI can be embedded directly into their service models.

Legal Services

Harvey: An AI platform built for the legal industry, designed to help lawyers and in‑house teams streamline routine tasks like contract review, drafting, due diligence, and legal research. Founded in 2022, the company combines large language models with domain‑specific training to deliver highly tailored outputs for complex legal work. Its AI agents operate within a firm’s existing workflow, extracting key information, highlighting potential risk areas, and generating first‑pass documents that attorneys can review and refine. Since its launch, Harvey has gained significant adoption across corporate legal departments such as T-Mobile, Bayer, and Repsol, and top‑tier law firms like Macfarlanes, A&O Sherman, and Paul Weiss. The company serves over 300 legal clients and has surpassed $100 million in ARR in July 2025.

Eudia: An AI‑enabled platform for in‑house legal teams, incubated by General Catalyst as part of its Creation Fund. The company emerged from stealth in February 2025 with $105 million in financing, $30 million of which was upfront and another $75 million contingent on Eudia finding acquisition targets. This structure reflects General Catalyst’s broader roll-up approach, blending venture-style company building with operational control, and focusing AI where traditional legal services have been slow to evolve. In July 2025, Eudia acquired Johnson Hana, a 300-person legal firm with clients including Airbnb, OpenAI, X, and Citibank. Eudia aims to embed AI deep into corporate legal departments, tackling routine and repetitive work such as compliance review, contract drafting, and risk assessments. Its platform combines AI agents with a structured data and knowledge layer, making complex information usable and actionable for lawyers.

The legal sector reminds us that services built around expertise ultimately revolve around people. Products like Casetext have shown how AI can make routine legal work more efficient, and platforms like Harvey and Eudia are making it possible for legal teams to focus more on higher impact work. But in this industry, technology alone doesn’t drive value. The best lawyers are the core of the business, and their trust, relationships, and judgment can’t be replaced by automation.

Atrium learned this the hard way. Its approach worked well for higher‑volume, repeatable legal work, where sales, marketing, and customer service could fill much of the role lawyers had traditionally played. But for lower‑volume, higher‑stakes practice areas, the ability to attract and keep top lawyers became the deciding factor. AI can help build more productive legal platforms, but only when they respect the central role lawyers play. The biggest opportunities will come from aligning technology, incentives, and culture in ways that support those lawyers, making their work more impactful and their firms more resilient, rather than treating them as interchangeable pieces.

Investment Advisory

Offdeal: An AI‑native investment bank built to reconfigure how M&A advisory works, focusing on lower‑middle‑market transactions that traditional firms often ignore. Founded in 2023, OffDeal replaces hierarchical deal teams with small two-person pods that use AI to identify buyers, benchmark performance, and draft pitches, so junior staff can focus more on judgment and client relationships. Its AI agents help match sellers with institutional buyers or locate acquisition targets across a database of millions of businesses, making advisory available to owners long overlooked by traditional investment banks. In doing so, OffDeal aims to reshape a fragmented market by putting M&A tools within reach of smaller businesses.

Inven: Inven is an AI platform built for investment professionals to streamline the early stages of dealmaking. It allows users to find relevant private companies across industries by extracting and analyzing data from millions of online sources using custom LLM pipelines, replacing the fragmented, manual research that typically goes into finding acquisition targets. Its coverage includes both lower middle‑market and middle‑market businesses, making it a valuable resource for advisors, corporate development teams, and investors alike. As of June 2025, Inven works with over 500 investment firms globally.

OffDeal and Inven approach the same gap from different angles. Inven focuses on making early‑stage research and sourcing more intelligent, extracting data from millions of sources to help advisors and investors find opportunities faster. OffDeal goes further by challenging the culture and structure of traditional investment banking. At large firms, modern tools like Zoom transcripts and data APIs already exist, but hierarchical incentives and bottlenecks keep them sidelined. True efficiency gains don’t come from bolting AI onto old workflows, but from starting with a new organizational design. Centerview proved this approach can work for large deals, and OffDeal is now aiming to apply this to smaller, fragmented transactions.

Contact Centers

Replicant: A call center automation platform that applies voice and conversational AI to routine customer interactions. Its approach is designed to help businesses resolve common inquiries more quickly while allowing human staff to focus on more complex or nuanced calls. Replicant handles tens of millions of customer calls per month, working with enterprise clients across different industries, including ADP, DoorDash, Fanatics, and National Debt Relief. Its AI agents draw on a growing array of multi‑industry conversation data, making it one of the more mature offerings in a space that includes both early-stage startups and larger cloud providers.

Crescendo: An AI‑native contact center platform incubated by General Catalyst in January 2024, blending operational expertise with advanced automation. In addition to building its own AI tools, Crescendo owns and operates call centers. As of August 2025, Crescendo had acquired one call center, PartnerHero, in October 2024. According to co-founder Anand Chandrashekran, Crescendo was generating roughly $90 million in annual revenue by May 2025, making it one of the largest AI‑focused entrants in the contact center space. Its long‑term goal is to create a more productive and sustainable model for customer support by embedding AI at every level of the operation, from automating common requests to reshaping how agents and customers work together.

The examples of Replicant and Crescendo highlight how AI is reshaping the contact center space, especially where traditional approaches have relied heavily on manual work and fragmented technology. From a customer’s perspective, Replicant offers more control and customization, making sense if you want to run your own operation. Crescendo delivers a fully managed experience, a better fit for those looking for outcomes rather than tools, with less operational lift required.

The Playbook

AI’s uneven impact leaves founders and investors with a practical question: which structure turns technology into reliable cash flow, while de-risking against the reality that 42% of generative AI pilots have failed to deliver measurable results? William Thorndike's book, The Outsiders, shows that leaders who outperformed their peers historically were able to do so because they reassessed where every new dollar could earn the highest risk-adjusted return.

The same mindset applies here: deciding where each additional dollar and week of effort earn the highest return inside your own business. The traditional SaaS model would devote the majority of incremental dollars to headcount and marketing. The AI rollup model has a much broader toolkit to choose from. However, charting workflows and refining models only shows where gains might lie, but turning those possibilities into actual value still depends on how each additional dollar and hour is deployed.

Viewed through that lens, modern AI businesses still cluster around three workable entry models: (1) license software and let incumbents handle operations, (2) buy proven assets, install technology, and recycle the resulting cash, and (3) build a full-stack company so that code, capital, and daily control stay under one roof.

In practice, many operators will blend elements of each of these or pivot as market conditions shift, but treating them as distinct archetypes forces a clear first choice and provides a baseline against which to measure course corrections. The playbook that follows lays out the approach operators can take in identifying market inefficiencies, proving the potential impact from AI, and then picking an initial strategy between selling, buying, or building the “customer.”

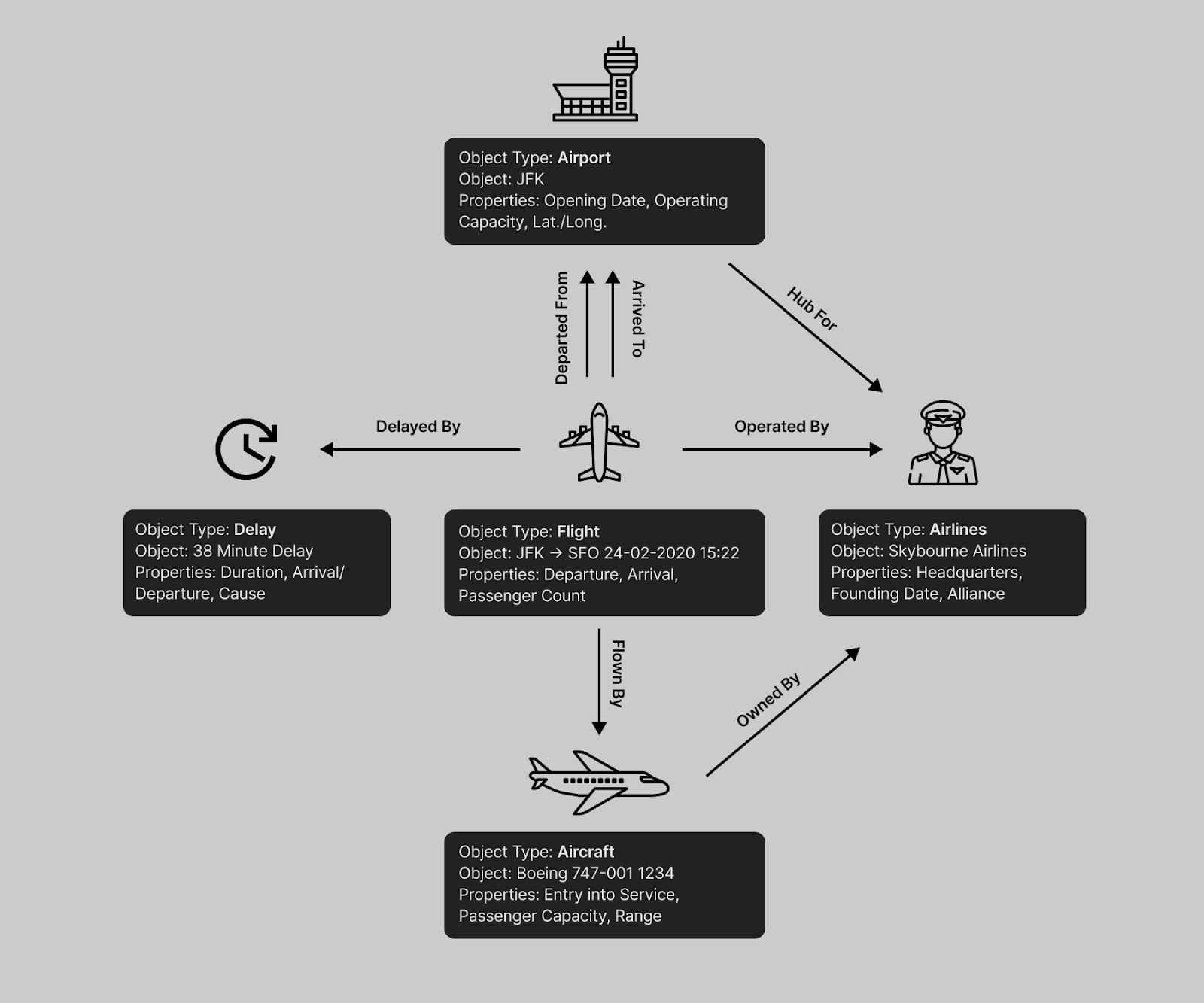

I. Map The Ontology

One proposal borrows from Palantir and starts with mapping out the end user's business ontology, as it exists in the status quo. This entails a formal map of the objects that flow through the business, the states they can assume, and the actions that move them from one state to the next. Drawing that graph uncovers the transitions that absorb disproportionate time, headcount, or capital. By making those frictions explicit, you set the scope for improvements and jobs to be done. Palantir’s early insistence on ontologies and decision to model every step of the workflow before writing code illustrates how a detailed map lets teams prioritise R&D spend and align investors around a shared view of value creation.

Source: 8VC

II. Define The Terrain

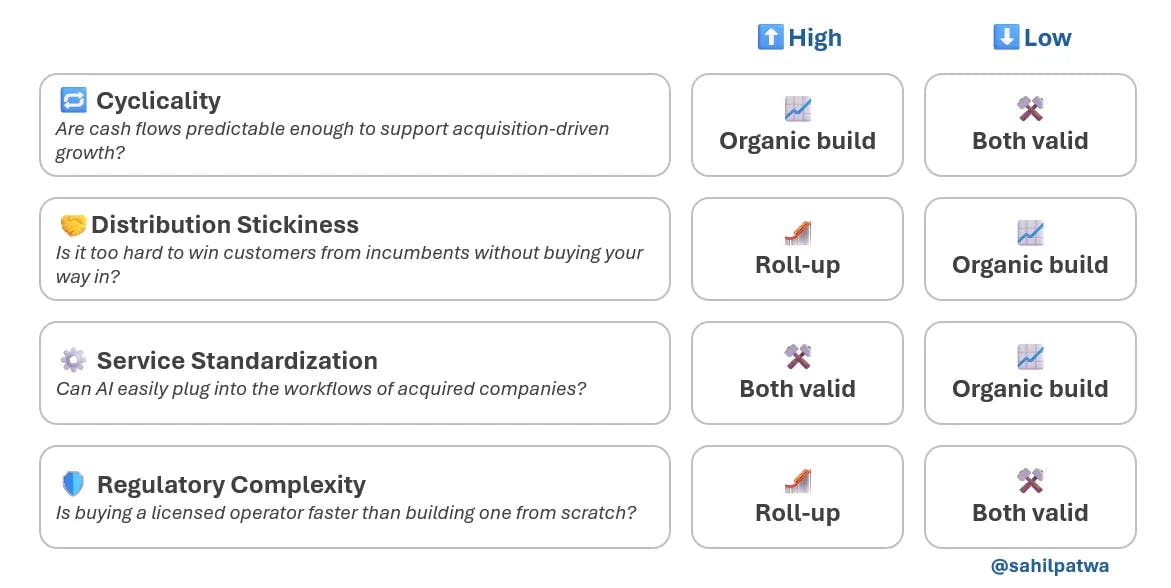

Once the inefficiencies are on paper, step back and ask whether the surrounding market structure actually rewards taking control of the full P&L. Mid-sized, owner-operated niches with 150-200 viable targets are often ripe for roll-ups, while industries concentrated with micro-operators can usually be served faster by a vertical SaaS wedge. Low-margin sectors where AI touches not just back-office paperwork, but the core service, offer the chance to lift EBITDA and therefore justify ownership. Conversely, highly cyclical or already tech-friendly categories make pure SaaS safer. Regulatory density may also be important. Buying a firm that already holds hard-won licences can shortcut years of compliance grief.

Source: Sahil Patwa

III. Prove, Then Buy

Before levering up, the goal is to show that the model moves numbers in the real world. The cheapest way to do this is to pilot inside a customer’s operation or to stitch together off-the-shelf AI components and run controlled experiments. Slow Ventures warns that value creation must precede M&A: “only buy if the product absolutely rips (generates tons of value). You wouldn’t hire a sales team before building a product, and M&A is just a go-to-market motion here, so build then buy.” Small pilots let founders prove that the technology really works, and give investors a clearer view of the gains before greenlighting M&A.

Source: Slow Ventures; Contrary Research

IV. Test The Distribution Wedge

When it’s slow or expensive to win customers with pure SaaS due to long contracts, reluctant users, or heavy onboarding, it can sometimes be cheaper to buy a company that already owns those relationships. Property management roll-ups illustrate this. Landlords usually change vendors only at lease renewal, so acquiring the incumbent slashes customer acquisition cost and turns that inertia into a moat. This is precisely what Metropolis encountered, which later resulted in its acquisitions of property managers Premier Parking and SP Plus.

V. Match Capital & Talent To The Path

Taking over existing operations introduces two extra skill sets beyond building product: M&A and day-to-day service delivery. Any successful attempt must handle debt structuring, integration playbooks, and a lean headquarters budget. It would also need a balance sheet that can safely carry debt without breaking covenants, a hard lesson from Thrasio’s 2024 collapse when its debt mountain strangled cash flow. If the people or capital involved can’t meet that standard yet, staying asset-light might be the best option.

Source: Contrary Research

Blurring The Lines

AI can expand margins, but how much and how fast depends on the entry model. Over time, the boundaries between vertical SaaS, roll-up, and full-stack are likely to blur even further, but the sequence of questions remains the most economical way to decide where to play at any given moment. Technologists moving into operator-heavy businesses face several hurdles:

Operational lift is hard. Achieving real efficiency gains, especially with immature AI tooling, requires disciplined process redesign, not just model integration.

Prices still matter. Historical roll-up returns relied on buying at low EBITDA multiples and exiting at higher ones. AI does not exempt acquirers from valuation discipline; overpaying for targets erodes the margin expansion AI is supposed to deliver.

Deal and integration skills are scarce. Running tuck-ins and managing debt covenants call for a playbook closer to private equity than product management. Most AI roll-ups will need blended teams, with operators, deal leads, and technologists balancing speed with risk control.

We are still in the early beginnings of this consolidation cycle. Many firms will experiment with hybrid structures, and some will discover that their initial model no longer fits as technology, capital costs, or customer behavior shift. The best outcomes will come from teams that can match the tool, structure, and market, while having the discipline to walk away when the fit isn’t there.

“I am a better investor because I am a businessman and a better businessman because I am an investor.”

— Warren Buffett

*Contrary is an investor in Ramp and Teamshares through one or more affiliates.