The Pentagon’s Prime Problem

In September 2025, President Trump signed an executive order giving the Department of Defense an external face-lift; reclaiming the Department’s former name: the Department of War. At least for marketing purposes. Without an act of Congress, the Department’s official title remains the Department of Defense. While the shift represents an acknowledgement of growing geopolitical conflict, it doesn’t necessarily strike at the heart of the DoD’s crisis of its own making.

For decades, the US industrial base that supports America’s military capabilities has been shrinking and consolidating, leaving the Pentagon dependent on a handful of prime contractors. 54% of the Pentagon’s $4.4 trillion in discretionary spending from 2020 to 2024 was allocated to contractors, with the “primes,” such as Lockheed Martin ($313 billion), RTX ($145 billion), and Boeing ($115 billion), receiving the bulk of the payments. Now, faced with rapid technological advancements from strategic competitors, the DoD has publicly acknowledged it can no longer rely solely on this legacy model.

The Secretary of Defense, Pete Hegseth, has stated his intent to transform the industrial base of the Pentagon: “Rebuilding plans involve reviving the defense industrial base, reforming DoD acquisition processes, and rapidly fielding emerging technology”. The official strategy, articulated in documents like the 2024 National Defense Industrial Strategy (NDIS), calls for a more "resilient, innovative, and dynamic" ecosystem.

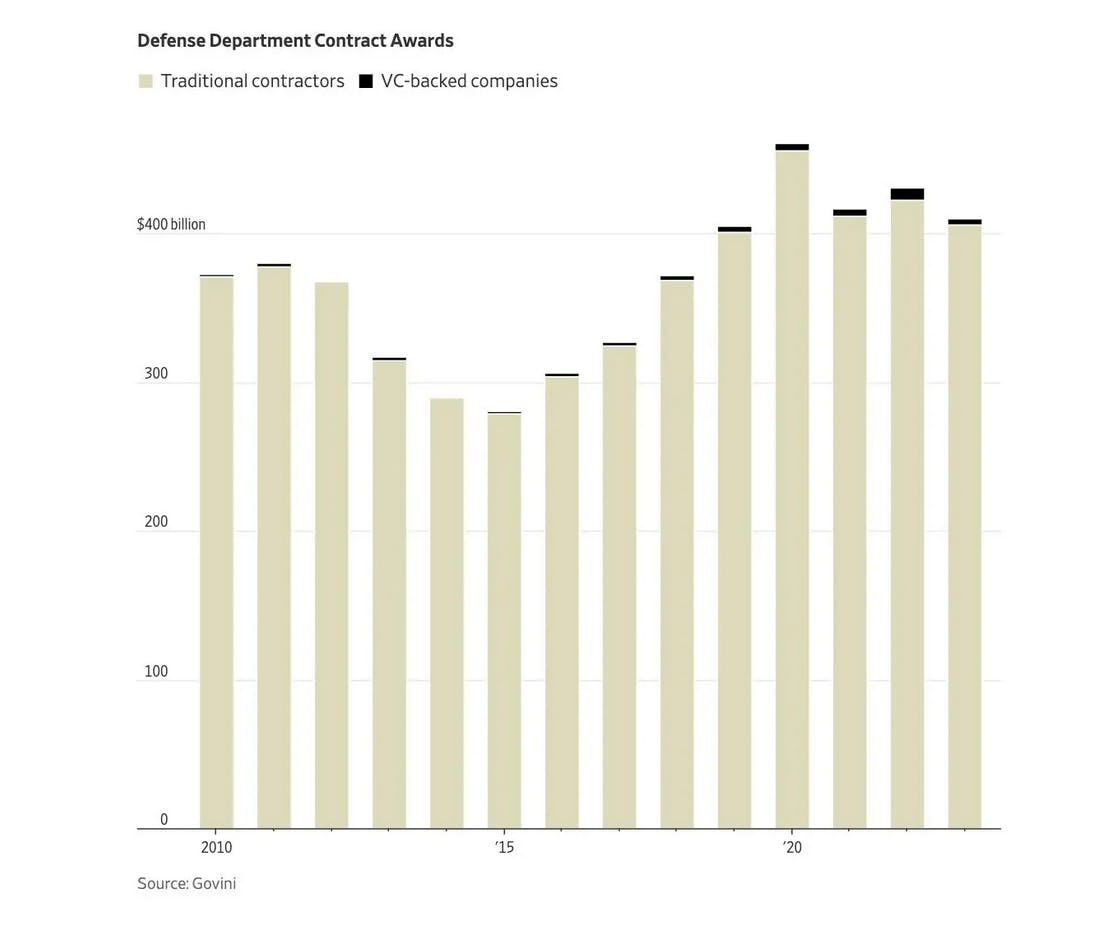

The Pentagon has already rolled out a suite of initiatives like the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) and AFWERX, designed to court Silicon Valley and other non-traditional innovators. The message is clear: the Pentagon wants to change. However, a closer look at the data reveals a disconnect between rhetoric and reality. While the Pentagon is spending more on startups than ever before, the contracts handed out to these startups amount to a mere rounding error; 0.2% of its colossal budget. This raises the critical question: Is the DoD’s pivot a genuine strategic shift, or is it merely a well-marketed experiment while the real money continues to flow into a broken system?

Lack of Competition & Slowdown in Innovation

The case for diversifying away from the traditional primes is written in the defense department’s own budget overruns and schedule delays. The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, handed to Lockheed Martin in 2001, serves as a quintessential example. Originally estimated to cost $244 billion in 2004, the program's total acquisition costs have ballooned to over $485 billion, with lifecycle costs projected to exceed a staggering $2 trillion. One September 2025 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report detailed how the F-35’s crucial "Block 4" modernization is now more than $6 billion over budget and at least five years behind schedule.

The lack of competition in these massive projects has also led to lucrative payouts for underperforming contracts. In 2024, Lockheed Martin delivered 110 F-35s to the DoD, every single one of which was late, by an average of 238 days. Despite this, the GAO noted that the program's incentive structure allowed contractors to pocket hundreds of millions of dollars in performance fees.

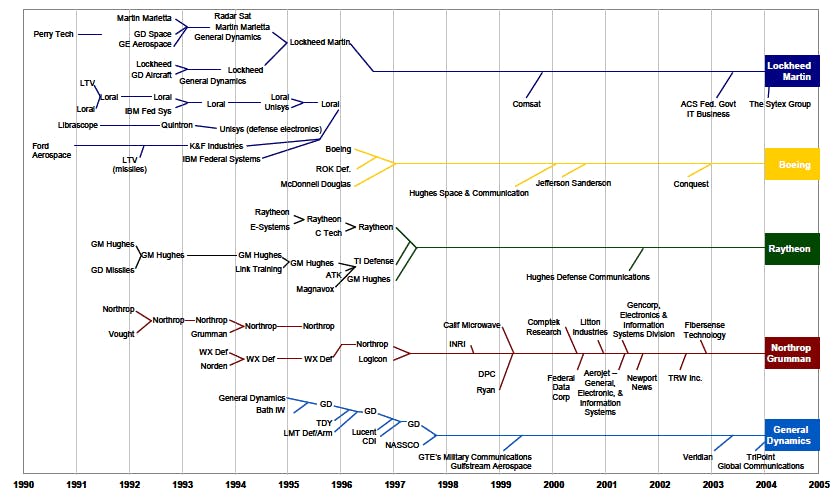

This pattern of underperformance is not isolated. From Boeing's troubled Starliner and KC-46 tanker programs to persistent issues with other major platforms, the symptoms of a non-competitive market are clear: soaring costs, chronic delays, and a lack of accountability. Nearly two-thirds of major weapons systems contracts in the United States have just one bidder, causing little to no pressure for current primes to competitively innovate. This isn't just a failure of project management; it's a systemic consequence of an industrial base that has withered from over 50 prime aerospace and defense contractors in the 1990s to just five today.

Source: David R King

Military technologies of the future, from autonomous systems, to cyber defense, and space technologies, are all enabled through the latest and greatest software. Yet the prime-centric model is optimized for developing massive, exquisite physical platforms over decades-long timelines; a process inherently resistant to the rapid, iterative development that characterizes modern development. The war in Ukraine has served as a stark wake-up call to this new reality, with successful Ukrainian drone operations being conducted on a limited time frame and shoestring budget, and massive cyber attacks being conducted by Russia, disrupting a broad swath of infrastructure. Victory on the modern battlefield is no longer solely determined by superior tanks or fighter jets. The creative use of cheap, commercial-grade dual-use technology for surveillance and attack, the resilience of decentralized satellite communications like Starlink, and the rapid, battlefield-driven development of software that fuses intelligence from disparate sources, are now becoming central factors in combat.

The US military is in dire need to transform its antiquated arsenal. As Palmer Luckey, the CEO of Anduril*, likes to point out, there are more AI capabilities in a Tesla than any US Military vehicle, and better computer vision technology in the Snapchat app than any system the Pentagon owns. While the legacy contractors have been attempting to explore this market, the bulk of these innovations are still coming from Silicon Valley, where its software and AI expertise provide them with an inherent edge.

The Next Generation

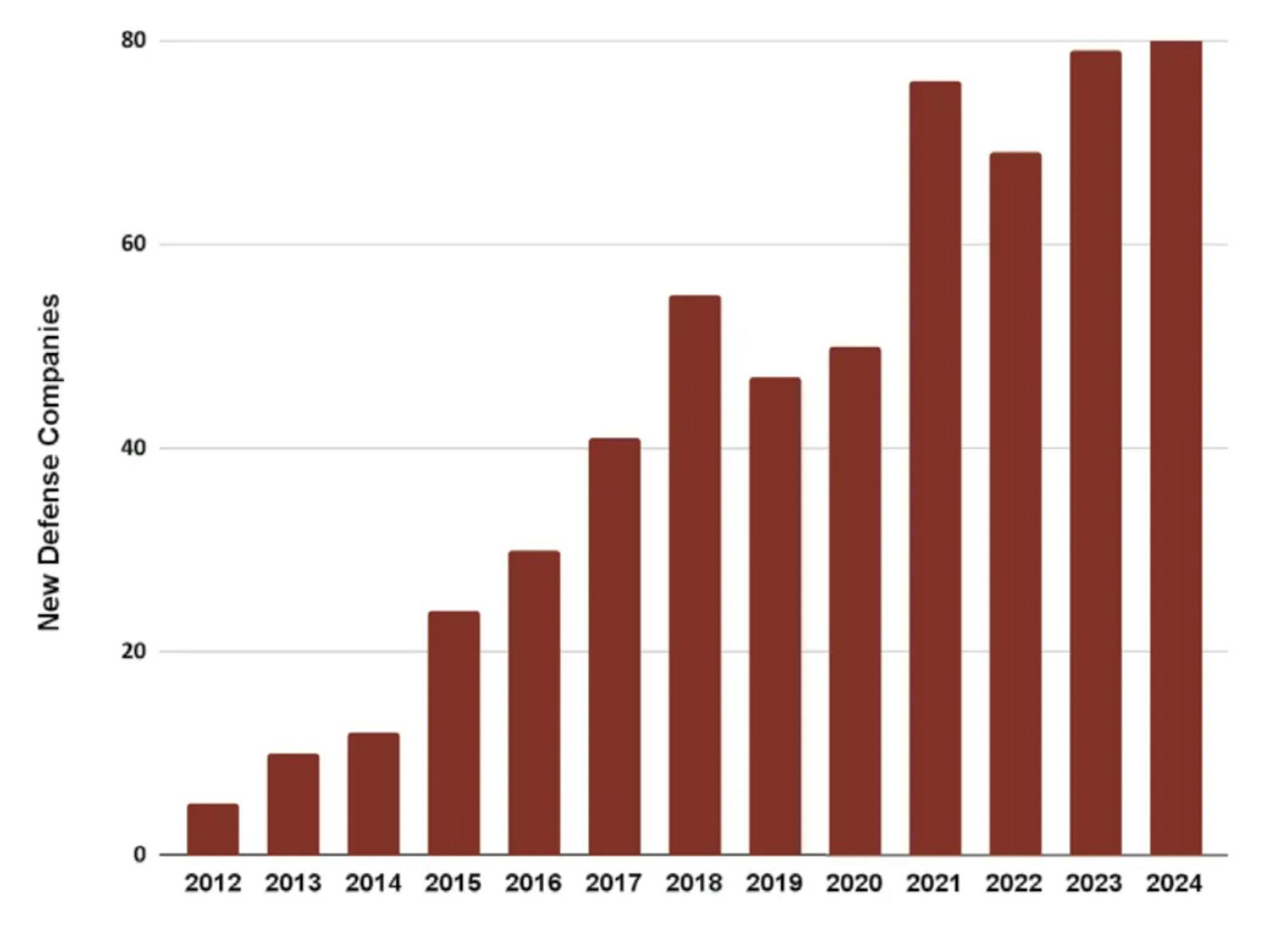

The obvious need for reinvention has acted as a beckoning call to a new generation of innovators. Despite the DoD’s inability to get out of its own way on technology acquisition, the $755 billion worth of contracts handed out by the Pentagon is a large enough pie to entice these companies regardless. First-movers, like Anduril*, Shield AI, and Palantir, have proven that startups can break into the notoriously opaque defense market and achieve significant scale, a new generation is trying to tap into this field of success.

Over 250 new defense and dual-use startups raised Series A funding or more from 2022 to 2024, creating a diverse and competitive ecosystem that could help drive innovation. These companies specialize in areas where the primes have traditionally lagged and where they think the future of warfare will be headed: autonomy (Saronic and Overland AI), advanced manufacturing (Hadrian and Mach Industries), space (True Anomaly and Impulse Space) and AI-native command and control (Vannevar Labs).

Source: Hoover Institute

Venture capital firms, once cautious to engage with the Pentagon’s long timelines and bureaucracy, are beginning to aggressively fund this new ecosystem. According to a 2025 report, VC investment in US aerospace and defense startups surged to over $35 billion in 2024, a nearly 40% increase from 2022 levels. However, despite the massive funding increase, DoD contracts awarded to these startups have barely grown. Venture-backed companies were awarded less than 1% of the $411 billion Defense Department contracts in 2023, only slightly larger than the 0.5% awarded in 2010, when only a small number of startups were even building military technology. Defense contract managers remain cautious about handing out lucrative contracts to unproven startups whose tech isn’t widely used and could still fail to materialize. Without contracts from the Pentagon, these startups face massive financial risks. In many cases, the government is the only viable customer, leaving these companies with limited options to pivot towards.

Source: Wall Street Journal

New Programs, Old Politics

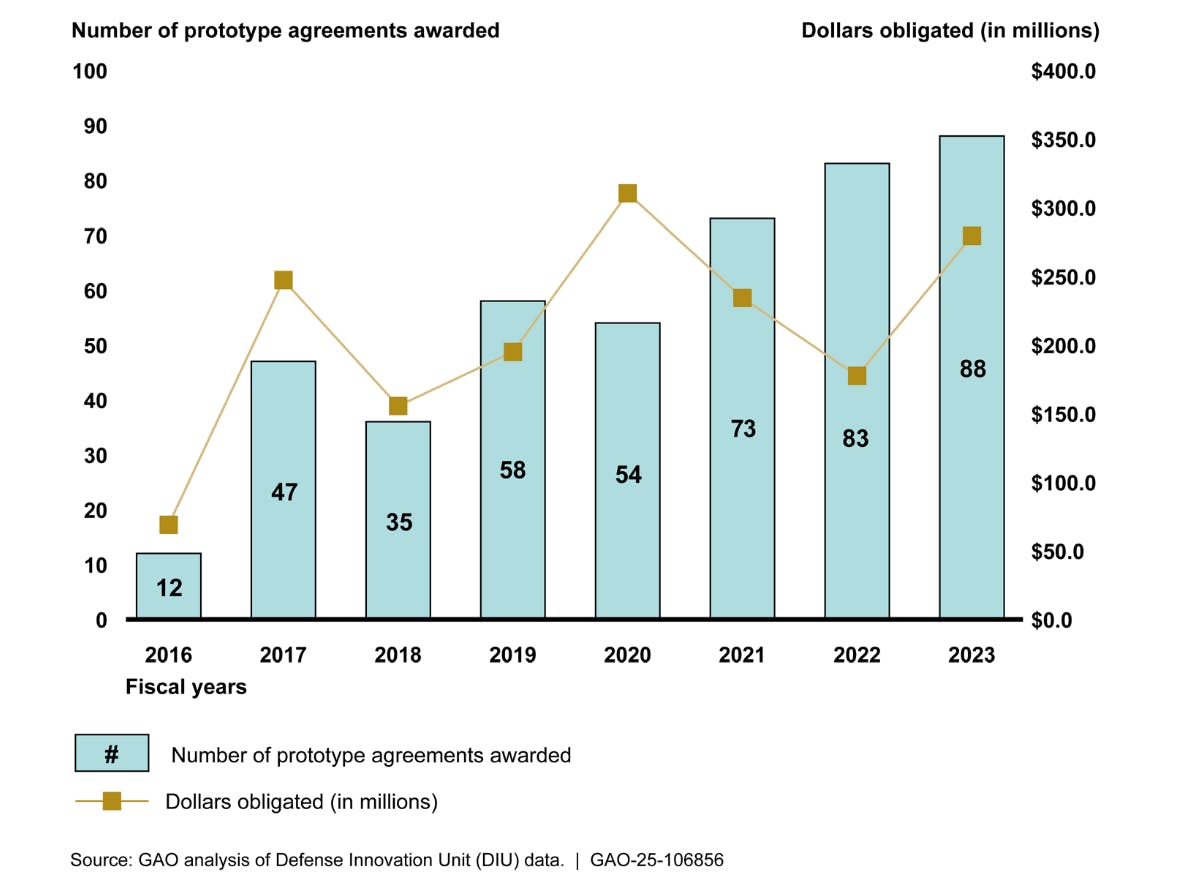

In response to the challenge of adoption, the Pentagon has established several initiatives aimed at lowering the barrier to entry for startups and accelerating the adoption of commercial technology. Leading this charge is the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), established in 2015 to act as a fast-moving conduit between the Pentagon and non-traditional tech companies. Headquartered in Mountain View, the DIU utilizes flexible government contracting mechanisms such as Other Transaction Authority (OTA) to award prototype contracts in as little as 60 to 90 days; a stark contrast to the years-long traditional acquisition cycle.

The DIU has seen a dramatic increase in funding in recent years, with its budget skyrocketing to $945 million in 2024, up from the $107 million it received in 2023. This funding boost is earmarked to expand and accelerate funding towards strategic areas, particularly in autonomous systems, and to launch new initiatives in counter-unmanned aerial systems, space transport, and advanced manufacturing through programs like the Blue Manufacturing initiative, which aims to build a resilient and secure industrial base. The department also hosts an in-house accelerator program, called the Defense Tech Accelerator Challenge, which seeks to identify and support cutting-edge innovations that address critical DOW needs.

Source: Government Accountability Office

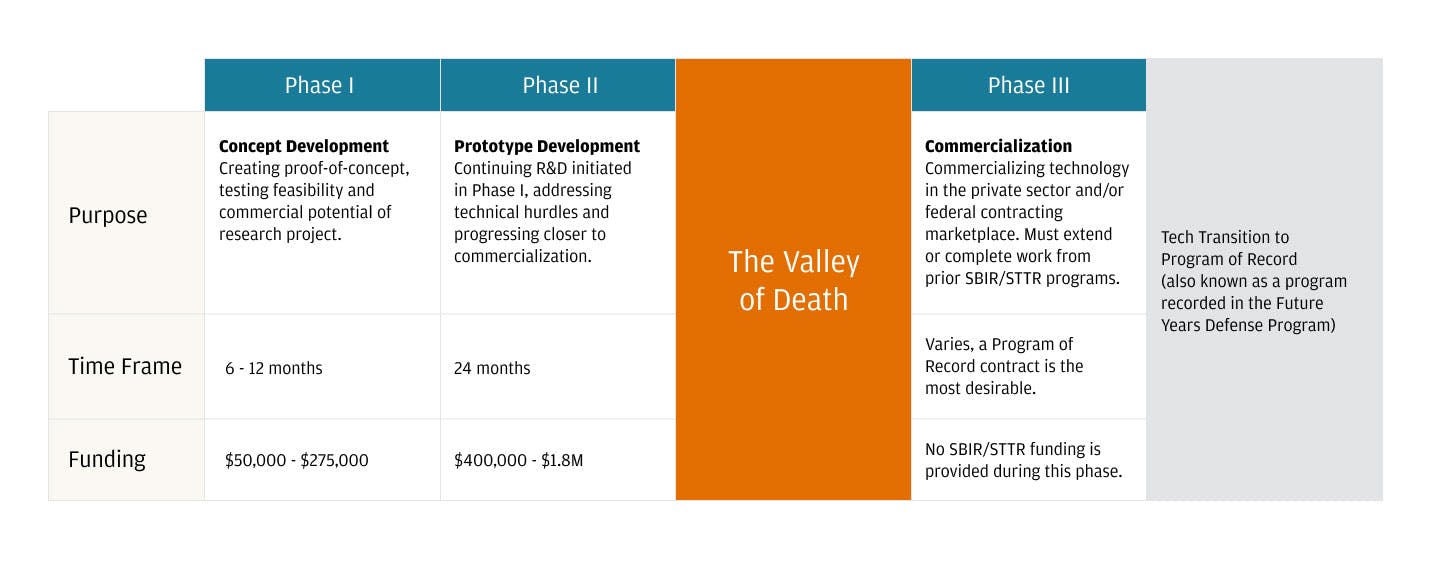

Alongside DIU are long-standing programs, such as the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program and the Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) program, which provide billions in early-stage R&D funding. However, these programs have historically struggled to bridge the so-called “Valley of Death”. The perilous funding gap between a successful prototype and a large-scale production contract, with fewer than 1% of initial awardees reaching commercialization. To address this persistent failure, a new wave of reforms and initiatives is being proposed that go beyond simply funding prototypes. The Office of Strategic Capital (OSC), established in 2022, is now authorized to issue loans and loan guarantees, leveraging nearly a billion dollars to attract private investment for companies scaling critical technologies. The hope is that this influx of capital, along with the ample VC funding, will help companies scale past prototypes and into production.

Source: J.P.Morgan

Finally, each branch of the armed forces has also created programs to accelerate startup adoption, recognizing that a one-size-fits-all approach is insufficient to capture the breadth of commercial innovation.

The Air Force has been particularly aggressive through AFWERX, its innovation arm, which has four core divisions: AFVentures, focused on investing in emerging technologies; Spark, a grassroots program for Airmen and Guardians to solve operational problems; Prime, which accelerates the transition of commercial tech into military use; and SpaceWERX, focused on newly developed space technology.

The Army has established its Army Futures Command (AFC) in Austin, Texas, to streamline modernization and works closely with startups through entities like the Army Applications Laboratory (AAL), which helps new companies navigate the defense acquisition process, with focuses on both dual-use and specialized startups.

Similarly, the Navy has launched NavalX as an innovation cell for the Navy and Marine Corps, operating a network of "Tech Bridges" across the country to facilitate local collaboration. The Marine Corps further leverages the Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory (MCWL) and the Marine Innovation Unit (MIU), a reserve unit of civilian tech experts, to identify and experiment with future warfighting capabilities.

Despite all these initiatives, adoption has remained stagnant, highlighting the bureaucratic process of obtaining these contracts. To circumvent this process, the most highly valued, venture-backed startups are beefing up their presence in Washington. In 2023, nearly $6 million was spent on lobbyists, and companies such as Anduril* are hiring former members of the Senate Armed Services Committee to help win these pivotal contracts. This creates a difficult situation for smaller startups, as it effectively re-establishes the high barriers to entry that innovation initiatives were meant to dismantle. This trend signals a shift where success in the defense market once again depends not just on superior technology, but on mastering the "inside game" of Washington politics; a game that requires significant capital and connections. Smaller, early-stage companies, which may have the most novel technologies, lack the resources to hire expensive lobbying firms or recruit high-profile former officials. As a result, they risk being crowded out, unable to get their solutions in front of the right people, regardless of merit. This creates the risk of a two-tiered system where well-funded "new primes" learn to operate like the legacy contractors they sought to replace, while the broader ecosystem of innovators remains stuck behind a wall of bureaucracy and political influence.

The Geopolitical Imperative

Ultimately, the drive to reform the Pentagon’s innovation model is a direct response to a new era of geopolitical competition against the likes of the People’s Republic of China. Simulated war games conducted by the Pentagon over the last decade has seen China’s advanced weapon systems, those designed specifically to neutralize and surpass our own, come out on top. The United States is at risk of falling behind adversaries who can develop and field new capabilities in a fraction of the time it takes the legacy US system. In 2018, Under Secretary for Research and Engineering Mike Griffin stated that, on average, it takes the US sixteen years to deliver an idea to operational capability, compared to under seven years for China. This creates a dangerous asymmetry where America's overwhelming military budget does not translate into proportional military advantage.

We’ve demonstrated that the core issue is not a lack of funding, or acknowledgement of need from individual branches of the military, but rather a legacy system that incentivizes slow, exquisitely expensive hardware programs over the rapid, software-driven, and more affordable systems that define modern warfare. If the Department of Defense is going to have any hope of changing that paradigm, it must fundamentally reorient its acquisition and development processes. This requires a strategic pivot away from exclusively contracting with the current “primes” and providing more opportunities for innovative upstarts to earn these lucrative contracts.

By fostering a truly competitive industrial base that encompasses small-scale startups and maintain the strong suit of the primes, the Pentagon can harness the speed and agility of the commercial tech sector. The ultimate goal is to restore credible deterrence, not by outspending adversaries, but by out-innovating them, fielding a more resilient and adaptable force capable of winning the conflicts of the future. While the recent influx of initiatives is a good start towards this goal, the brittle bureaucratic process and difficulties in bridging the “valley of death” still remain significant hurdles in driving innovation into adoption.

*Contrary is an investor in Anduril through one or more affiliates.