Calls to "bring back American manufacturing" often evoke images of bustling factory floors and millions of returning jobs, but the reality is far more nuanced. What manufacturing can the US actually aim to reshore? Is there any truth behind claims that a US-built iPhone would cost $30K? And does America have the automation capacity to compete globally with manufacturing giants like South Korea and China?

The reality? The US can, in fact, rebuild a thriving manufacturing base, but not by resurrecting every low-wage assembly line that left decades ago. Its industrial future likely lies in high-tech, high-value production supported by automation as opposed to labor-intensive commodity goods.

America’s Comparative Advantage in Manufacturing

Not all manufacturing is created equal. Policymakers such as US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimon and technology industry leaders like Intel have already committed large investments in reshoring high-tech manufacturing. And they should continue to place their focus on reshoring strategic, high-value industries like semiconductors, advanced electronics, aerospace, defense, EV components, and pharmaceuticals, rather than recreating every low-cost consumer goods factory.

The US still manufactures extensively, though its industrial base has shifted toward high-tech sectors where American innovation and skilled labor offer clear advantages. While total US manufacturing employment has declined since the 1990s, real output (adjusted for inflation) reached near-record highs in the late 2010s, according to Federal Reserve data. The increases in output is most evident in electronics and vehicle production. For example, computer manufacturing has surged by over 1.2K% from 1994 to 2018, and vehicle production has risen more than 60% in roughly the same period (index for motor vehicle output was approximately 100 in 1994 and increased to around 160 by 2023, representing a ~60% increase).

By contrast, the greatest declines have come in low-value, labor-intensive sectors like apparel, textiles, and basic consumer goods. Apparel and leather goods output has fallen by over 60% since 2007 as production moved to cheaper labor markets. Bringing back these low-end jobs would be economically impractical. If we somehow reversed the offshoring of commodities like clothing and toys, it would mean pushing relatively prosperous manufacturing workers back into lower-paying jobs, producing clothing and shoes with minimal economic benefit. Other countries simply produce T-shirts, toasters, and trinkets far more cheaply. As one analyst noted, "Our workers don't make many T-shirts or toasters; other countries can do it more cheaply", while the US focuses on high-end output. America's comparative advantage is no longer in sweatshop-grade industries. It's in advanced manufacturing and innovation.

The US industrial base hasn't disappeared; it has evolved into something more productive, specialized, and capital-intensive. This evolution means factories employ fewer people but produce more value. Even if policies forced some low-end production back, the resulting products would be more expensive, and jobs would be relatively low-paying. As economist Veronique de Rugy observes, protectionist efforts "won't bring back the past or revive old jobs. It will just make the future more expensive and shift workers into lower-paying jobs".

The Myth of the $30K "Made-in-USA" iPhone

A widely circulated claim in reshoring debates is that an iPhone built entirely in the United States would cost a staggering $30K. This figure is often used to highlight the supposed impossibility of manufacturing complex consumer electronics in high-wage countries like the US. But when scrutinized, it becomes clear that the $30K estimate is a myth. It is an intentionally hyperbolic projection that misunderstands where value is added in the iPhone’s supply chain.

According to Forbes, the true cost increase of making an iPhone in the US is far more modest, especially if we separate assembly from component fabrication. Assembly, which is the final stage where all the parts are put together, represents a very small portion of the iPhone’s total cost. For instance, data suggests that the iPhone 7 cost Apple about $224.80 to manufacture in 2016, with assembly in China (via Foxconn) accounting for roughly $8.00 of that total. If this assembly were relocated to the US, labor costs might rise several-fold, but even assuming a 5x increase, that would only bring the added cost to around $40 per unit.

What about building every component domestically? That’s where things get more complicated. The iPhone relies on a globally distributed supply chain, with memory chips from Korea, screens from Japan, and processors from Taiwan. Replacing this network with domestic production for each part would likely increase costs significantly, perhaps by hundreds of dollars per unit. But certainly not to $30K. The Forbes analysis suggests that a US-made iPhone, factoring in domestic fabrication of every part, would cost about $600–$700 more than current models, not 30 times more.

So, where did the $30K claim originate? It appears to stem from a theoretical exercise that combines worst-case assumptions across every part of the production chain, including drastically inflated labor costs, nonexistent US supply chain capacity, and high capital expenditure to replicate the scale and precision of Asian fabs. In reality, the main barrier to reshoring iPhone production isn’t that it would suddenly become unaffordable, but that the US lacks the integrated infrastructure. Think the supplier networks, skilled technicians, and logistical systems that are currently available in China and East Asia.

Apple doesn’t manufacture in China purely because of low wages. As Tim Cook noted in 2017, “In the US, you could have a meeting of tooling engineers and I'm not sure we could fill the room. In China, you could fill multiple football fields.” That’s not an exaggeration. China has built entire cities like Shenzhen optimized around electronics manufacturing, with a dense cluster of component suppliers, tooling specialists, and engineers all within arm’s reach. Attempting to recreate this in the US would require not just more expensive labor, but massive upfront investments and years of capacity-building.

The $30K iPhone serves more as rhetorical flair than economic reality. A US-built iPhone would cost more, but likely in the range of 10% to 30% more, not 3000%. The real issue is ecosystem readiness, not just wages. If the US wants to seriously reshore high-tech assembly, it must build out the underlying manufacturing infrastructure, retrain a specialized labor force, and invest in advanced automation. The answer is not to succumb to fearmongering over fantasy price tags.

Can the US Compete with China?

If high labor costs are the barrier to low-end manufacturing, the solution is automation. Advanced economies remain manufacturing powerhouses by using robots to massively increase productivity. Does the US have the automation infrastructure to make reshoring competitive?

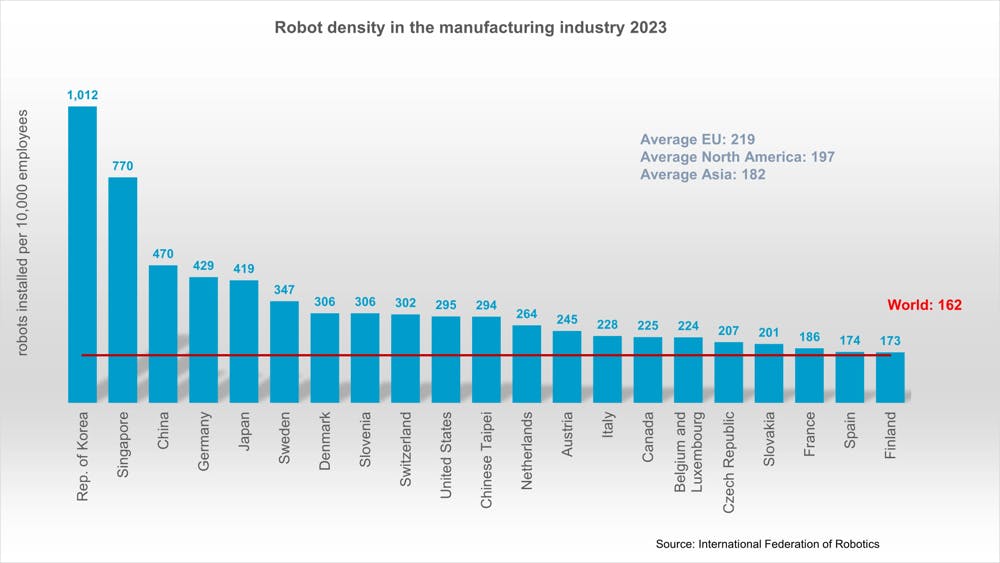

Data suggests that America lags in industrial robotics adoption. Robot density, defined as robots per 10K manufacturing workers, shows the US at 295 per 10K, ranking roughly 10th globally. This is half the level of leaders like South Korea (over 1K per 10k) and now significantly below China's 470 per 10K. A decade ago from 2025, China wasn't in the top ten; now it has more robots per worker than America by a large margin.

Source: IFR

The gap is even starker in absolute terms. China installed over 276K new industrial robots in 2023 alone – 51% of all robots deployed globally. The US was third at only 7% of installations. China isn't just catching up; it's investing in automation at a pace America hasn't matched.

Why is the US trailing? Analysts point to policy differences. China's government aggressively promotes automation as a national strategy through subsidies and incentives. One study from September 2023 found China's robot adoption was 12 times higher than America's relative to wage expectations, meaning China automates faster than market forces alone would predict, thanks to substantial government support. The US offers virtually no automation incentives and has historically resisted promoting robotics due to "robots taking jobs" fears.

This disparity has clear reshoring implications. As one study stated, the only way for the United States to compete with dollar-adjusted lower manufacturing wages in China is for manufacturers in America to be more productive, and automation, such as robotics, is the key way to do that. High labor-cost nations can't win by matching low-wage countries on cost; they must out-innovate and out-automate.

Initiatives like the CHIPS and Science Act, announced in 2022, hint that policymakers understand the need for modern manufacturing infrastructure. However, catching up won't happen overnight. China's latest five-year plan continues prioritizing robotization and AI in factories, and its demographic trends (an aging workforce) virtually ensure it will keep replacing labor with machines. America must either embrace automation and retrain workers for future factories or struggle to compete.

The Path Forward

America can build things again, but cannot and should not rebuild the 20th-century factory economy of low-wage, low-value manufacturing. We let commodity goods go for structural reasons, and forcing them back would either make products prohibitively expensive or require replacing labor with machines in an economic equation that will struggle to make sense.

Instead, we need to focus on the right manufacturing. High-tech, high-value, strategic industries where domestic production enhances innovation and security. Semiconductors, advanced batteries, aerospace, defense, and critical medical supplies are all fields where American expertise leads, and supply chain resilience justifies cost premiums.

Success won't come from cheap labor but from advanced automation and skilled talent. The $30K iPhone claim, despite being wildly exaggerated, does hold a kernel of truth: without dense ecosystems and efficiencies developed overseas, transplanting complex manufacturing is enormously challenging. The path forward requires building that ecosystem domestically. Investing in robotics, training workers in cutting-edge manufacturing, and fostering supplier clusters around new domestic factories.

The future factory will have more robots and fewer line workers, but those workers will be better paid and more highly skilled. America can "make it here" again by creating 21st-century manufacturing hubs – highly automated, outputting world-class products, providing good jobs, and managing sophisticated technology.